For nearly 100 years, the high-fat, low-carbohydrate, calorie- and fluidrestricted ketogenic diet (KD) has been in continuous use, predominantly for children with seizures who have not responded to medication.1 Several recent reviews and meta-analyses have concluded that there is insufficient evidence supporting the use of the KD from class I (double-blind, placebo-controlled) studies, which is understandable considering the difficulty of blinding a dietary treatment.2,3 However, all of these reviews find it highly unlikely that the consistent reduction in seizure frequency noted in 50–60% of children started on the KD in now nearly 100 class II–IV studies is coincidental. In fact, considering that the likelihood of a seizure-free outcome is <10% with adjunctive anticonvulsants or vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) after several medications have been tried unsuccessfully, and that the seizure-free likelihood with the KD is 15–20%, the latter may be the preferential treatment in cases where resective epilepsy surgery is not a clear option.

How has the KD changed from an unproven, ‘alternative’ epilepsy treatment to an established, non-pharmacological medical therapy over the past decade? In this review I will discuss the five most exciting and dramatic changes in the use of the KD in the past 10 years, focusing specifically on future research.

Finding Ideal Candidates for the Ketogenic Diet

Just 10 years ago, it was traditionally thought that all children with epilepsy—regardless of seizure type, age, or any other demographic—were equally likely to respond to the KD.4 However, this no longer appears to be the case. Recent research has demonstrated, often in multiple publications from several distinct centers, that the KD may be more likely to be effective in children with infantile spasms,5,6 tuberous sclerosis complex,7 myoclonic–astatic epilepsy (Doose syndrome),8 severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy (Dravet syndrome),9 Rett syndrome,10 glucose transporter deficiency (GLUT-1),11 and generalized seizures (e.g. Lennox Gastaut syndrome),12 as well as children who are not candidates for resective surgery.13 In these situations there is a strong but unproven argument in favor of treating children with these epilepsy types and clinical situations using the KD early in the course of their epilepsy, perhaps even as first-line therapy.

Infants and children receiving a solely formula-based KD via bottle or gastrostomy tube (e.g. KetoCal™ or modular fat, protein, and carbohydrate liquid formulas) appear to have better seizure control than those receiving solid foods.14,15 There is also recent surprising evidence that children with epilepsy may have a stronger preference for high-fat foods than children who do not have seizures.16 If this finding translates to better outcomes on the KD for children with a fat preference, there may be a way of screening children with epilepsy for food preferences and eventual KD success. Lastly, studies have demonstrated that the KD and VNS 17 used together may be a synergistic combination therapy; this may also be true for the KD and zonisamide (unpublished data). Ongoing and future studies will continue to expand the list of ‘indications’ for the KD, as well as studying its use for these conditions at epilepsy onset, perhaps instead of standard anticonvulsants.

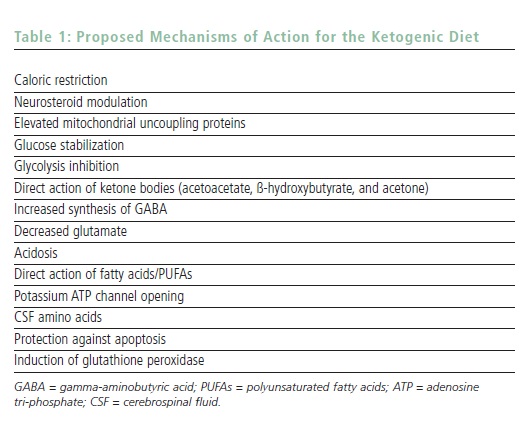

Determining How the Ketogenic Diet Works

The mechanism of action for the KD remains unclear, but is the subject of significant active research.18 When the body is deprived of carbohydrate, even during the fasting period, it is forced to metabolize long- and medium-chain fatty acids. In order to cross the blood–brain barrier, the liver metabolizes these fatty acids into ketone bodies, including ß-hydroxybutyrate, acetoacetate, and acetone. Ketone bodies can be measured in blood and cerebrospinal fluid, but also non-invasively in urine and breath to monitor levels of ketosis objectively. For years, ketosis was the only mechanism of action proposed for the KD’s efficacy. However, both recent animal studies and clinical research have suggested that, although ketosis may be a marker of the metabolic change that the body has appropriately undergone on the KD, other mechanisms may be at work for seizure control.

It seems logical based on current research that the KD is active on the mitochondria of neurons and positively affects energy balance. The major mechanisms under investigation in 2007 are listed in Table 1. One suspects that the KD likely has multiple mechanisms of action, and the particular epilepsy type (or neurological condition other than epilepsy) may dictate the manner in which the KD works. With new animal models and collaborations, the true answer(s) to why the KD works may be found within the next decade. Finding the mechanisms of action may also lead to the creation of a pill or shake that could simulate the KD without the need for dietary modification.

Identifying Easier, Safer Ways of Starting the Ketogenic Diet

The ‘Hopkins protocol’ for beginning children on the KD has traditionally recommended a 24–48-hour fasting period followed by a gradual increase in calories (using a fixed KD ratio of fat:carbohydrate and protein combined) over a three-day period (see Table 2).4 This is accomplished during a four- to five-day inpatient hospital stay in which children are closely monitored for hypoglycemia, acidosis, vomiting, and seizure reduction, while their parents are educated in how to use the KD in the future. Several well-performed retrospective and prospective studies have questioned the value of many aspects of this protocol. There is now excellent evidence that fasting is not required,19 although it may still be helpful in causing a more rapid seizure reduction; that the KD can be carefully started as an outpatient treatment with clinic visit education; and that the KD can be advanced either more rapidly or with full calories and a gradual ratio increase over two to three days. Having all of these new options for starting a child on the KD will certainly make the KD more attractive for a medically fragile child or a family with significant time or financial constraints.

Screening for—and Preventing—Adverse Events

Just 10 years ago, the side effects of the KD were rarely discussed, and were primarily described as weight loss, acidosis with illness, constipation, and possible dysmenorrhea. Perhaps no other aspect of the clinical use of the KD has been researched more in the past decade than the list of potential side effects of which neurologists and parents should be aware.20 Although rare side effects have been described, the more common (occurring in approximately 5% of cases) adverse events include slowing of linear growth, kidney stones, dyslipidemia, and gastrointestinal upset. Growth is adversely affected by the KD, probably as a combined effect of high ketosis, acidosis, relatively low protein, and concurrent anticonvulsant drugs.21 This seems to be more problematic in children under two years of age, and decreasing the KD ratio with additional protein may be helpful. Kidney stones occur in 5–6% of children on the KD and are correlated with hypercalciuria.22 The use of oral citrates (e.g. Polycitra K™) reduces the risk three-fold,23 and it may be reasonable to use these agents empirically in all children. Lastly, most children have a 30% increase in total cholesterol, triglycerides, and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol while receiving the KD.24 Fortunately, this appears to stabilize and possibly improve over months to years,25 but the long-term risk from temporary dyslipidemia on atherosclerosis remains to be seen.

Using Alternative, Less Restrictive Diets

In 2002, two children seen at Johns Hopkins Hospital set in motion a surprising chain of events that led to the creation of an alternative version of the KD, which has now been studied in a total of six papers from three countries.26–31 The first child was a seven-year-old girl with intractable complex partial seizures who was one month away from her scheduled admission for the KD. Her parents were counseled to restrict carbohydrates to ‘get her ready’ for the restrictions of the KD. Within two days of reading and following the Atkins diet book, her seizures had stopped, and one week later her KD admission was canceled. A second child, aged 10 years, had stopped the traditional KD one year previously due to seizure freedom. When his seizures began to recur, his mother started re-feeding him ad lib the high-fat and low-carbohydrate foods he had eaten in the past. Ketosis recurred and seizures stopped once again. These two cases led to prospective studies in now nearly 100 published children and adults using the ‘modified’ Atkins diet, which initially restricts carbohydrates to 10g/day (15g/day in adults) and encourages high-fat foods, but does not require hospital admission or a fast (see Figure 1). Protein, fluids, and calories are not limited; in fact, they are encouraged. In both children and adults results are surprisingly similar, with 47% of patients with intractable epilepsy having at least a 50% reduction in their seizure frequency. Ketosis occurs, but generally decreases over several months on this diet; however, this does not appear to correlate with efficacy except during the first month.29 Side effects include increased cholesterol and blood urea nitrogen (not creatinine, however) and weight loss.29 Interestingly, in adults weight loss correlated with seizure control at three months.30 Although still restrictive, the modified Atkins diet appears to work quickly, often within two weeks when effective.29,30

A single study from Massachusetts General Hospital in 2005 described an even less restrictive diet: the ‘low glycemic index treatment.’31 This diet restricts carbohydrates to 40–60g/day and does not restrict fluids or protein, but loosely monitors fat and calories. Unlike the modified Atkins diet, the type of carbohydrate is important in this diet, with only carbohydrates with a glycemic index <50 allowed. These carbohydrates include berries and wholegrain breads as opposed to potatoes, white bread, and most citrus fruits. Efficacy is also surprisingly good despite an absence of urinary ketones and only low levels of serum ketones.

Further studies of both diets in children and adults are under way. These alternative diets may be particularly helpful in developing nations due to their relatively reduced costs for foods and initiation in comparison with the standard KD. Unanswered questions include long-term efficacy, comparative efficacy versus the ketogenic diet, and the use of these diets for new-onset seizures. As preliminary evidence exists for the use of the KD for brain tumors, Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), migraine, Parkinson’s disease, bipolar disorder, autism, and brain injury, using a less restrictive diet that can be started on an outpatient basis may lead to further clinical trials for these new neurological indications.

Conclusions

In summary, the KD has undergone a renaissance in terms of basic science and clinical interest, as well as research, in the past decade; this will only continue to expand. In April 2008, there will be a five-day international conference in Phoenix, Arizona, devoted to the KD. Also under development is a 26-member international consensus guideline panel for the clinical management of children using the KD. More centers in more countries continue to offer the KD to children and adults with epilepsy.

Exciting future directions for the KD include: using this therapy earlier in the course of epilepsy (perhaps even for new-onset seizures); preventing side effects with diet modifications and supplementation from the very first day of treatment; expanding the use of alternative treatments such as the modified Atkins diet to increase usage for adolescents, adults, and even patients with neurological disorders other than epilepsy; and, lastly, potentially discovering a way of providing the KD as a pill or shake without the lifestyle modifications required with dietary therapy. The future of diets in the treatment of epilepsy and other neurological disorders is bright—so stay tuned.