Incidence

Incidence

Intra-parenchymal bleeding with or without extension into the ventricles and rarely into the subarachnoid space is recognised as spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH). Among all strokes spontaneous ICH accounts for approximately 10–15% cases, either primary or secondary.1 Chronic hypertension is regarded as the leading cause of the primary ICH, followed by amyloid angiopathy.2 Vascular malformation, coagulation abnormalities or intracranial tumours accounts for most cases of secondary ICH. Incidence of ICH ranges from 10–20 cases per 100,000 population.3 The mortality from ICH within the first months ranges from 44% to 51% and at two years post-ictus from 56% to 61%.4-6

There have been many studies showing the elevation of the blood pressure after ICH.7-10 Qureshi et al.,11 in their large cross-sectional study, showed elevated systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥140mmHg in 63% of stroke patients, and the proportion of the patients with ICH with elevated SBP ≥140mmHg were 75%. Prevalence of various blood pressure in ICH were as follows: SBP between 140 and 184mmHg was 50%; SBP between 185 and 219mmHg was 17%; and SBP >220mmHg was 3%.

Blood pressure elevation has been associated with poor clinical outcomes including death and dependency.10 This has been demonstrated in retrospective review by Dandapani et al.,12 in which they reviewed 87 patients with ICH with marked elevation of blood pressure on admission. The group of the patients who had SBP higher than 140mmHg had a higher rate of mortality.

Pathological Process

In order to understand how chronic hypertension influences the dynamics of the cerebral autoregulation we have to first understand the normal autoregulation of the brain. The cerebral autoregulation is maintained at the level of arterioles, which vasoconstrict with increase in blood pressure and vasodilate with decrease in blood pressure. These changes in vessel diameter maintain normal CBF under a wide range of cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP). The range of normal autoregulation is considered to be between 50 and 150mmHg. In chronic hypertensive patients there is a shift in the curve to the right, and thus patients with chronic untreated hypertension are at an increase risk of ischemic injury with sudden decrease in the CPP below the lower limit of autoregulation.

The exact reasoning behind the acute elevation of the blood pressure in stroke patients is not absolutely obvious; many different explanations have been put forward to define the acute elevation: first, it could be the reflection of the untreated hypertension;13 second, Cushing-Kocher response, which is a reaction from the compression of the brain stem;4,14 and third, abnormal sympathetic, parasympathetic activity, raised levels of circulating catecholamines15 and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP).16

Justification of Blood Pressure Management

The haematoma expansion as we know it is a dynamic process and usually progress for first 24 hours, with its peak expansion within first six hours.17-19 The relationship between the early elevated blood pressure with CBF changes and poor clinical outcome has been demonstrated in many studies and is illustrated below, but the relationship of elevated blood pressure with haematoma expansion is not clear, and it is also unclear whether the haematoma expansion occurs as a result of elevated blood pressure or is a consequence of that.20

It is not clear whether to treat hypertension acutely after ICH, as the reduction of the blood pressure on CBF is unclear. Animal studies have shown a transient decrease in the global CBF, especially in the perihaematoma region, which was presumed to be secondary to compression effect on the microvasculature.21,22 There is an impairment of the autoregulation in the perihaematoma and, as a result, sudden decrease in the blood pressure can lead to the vasodilatation which can increase the intracranial pressure (ICP) lowering the CPP.23

In an animal study performed by Qureshi et al.,24 there was no change seen in the CBF, cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2), and oxygen extraction fraction (OEF) in dogs with elevation of ICP and MAP after ICH. Subsequent authors with the help of radiological studies have come up with the similar conclusion. Hirano et al.25 and Zazulia et al.26 have shown no ischaemia in the periclot region by the use of positron emission tomography (PET), and Carhuapoma et al.27 have shown the same results with diffusion weighted image (DWI) in patients with acute ICH. From the above studies it is clear that there is no ischaemia in the perihaematoma. The toxic effects of the blood and its products in the perihaematoma can lead to the decrease in the metabolism.21,28,29

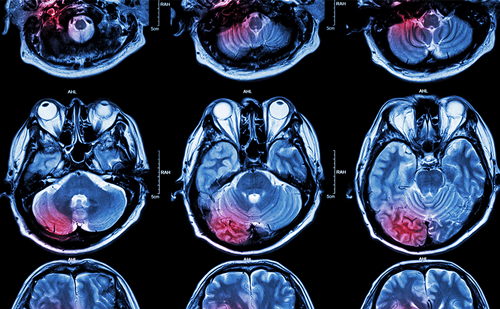

The CBF and metabolic changes in the perihaematoma evolves in three different phases (see Figure 1):

• hibernation phase, which is seen during the first 48 hours, and is defined as a reduction in the CBF and metabolism in both ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres;

• reperfusion phase, which is observed within 48 hours to 14 days and consist of heterogeneous pattern, including areas of normal, hypo- and hyperperfusion; and

• normalisation phase, which is seen after 14 days, and consists of normal blood flow except in non-viable tissue.30

The above theory, based on the careful laboratory and clinical evaluation, lays ground for the relative safety of decreasing blood pressure during the hibernation phase.

American Heart Association Guidelines

The American Heart Association (AHA) has put forward a set of guidelines with recommendation for the treatment of blood pressure in ICH. However, before the treatment, several different factors should be kept in mind; namely, chronic hypertension, ICP, age, mechanism of haemorrhage and time interval since onset. MAP should be maintained between 90 and 130mmHg.31 In patients with elevated ICP who have an ICP monitor, CPP should be kept >70mmHg.

Pre-clinical and Clinical Studies

The current literature supports the fact the elevation of the blood pressure is associated with poor neurological outcome, haematoma expansion, with no associated perihaematoma ischaemia. Thus, treatment of hypertension in an acute clinical setting should be considered an option, although what we do not know at this point is the parameter of the blood pressure control in order to sustain an adequate CPP.

Meyer and Bauer32 demonstrated the improvement in mortality in patients with ICH who were treated with antihypertensive medications; the results of this study were limited by the fact that the treated group had less severe symptoms. Dandapani et al.,12 have shown reduction in mortality and morbidity with the reduction of the blood pressure within 2–6 hours after ICH, but this study did not consider variables like ICH volume, ventricular blood, and initial Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS). Qureshi et al.,33 showed that pharmacological reduction of MAP in normotensive experimental animals is not associated with changes in ICP and CBF around and distant to the region of the ICH. The study has its limitations, as the animals were normotensive as opposed to the majority of patients who develop ICH having chronic hypertension. Powers et al.,34 looked at 14 patients and performed pharmacological reduction with the help of nicardipine and labetolol and showed that 15% reduction of MAP was not associated with any CBF changes in pre- and post-PET scan study. Qureshi et al.,35 in 2004 in a multicenter prospective trial, treated patients within six hours and between six and 24 hours. This study clearly showed that patients who were treated within six hours were more likely to be independent at one month compared with patients who were treated between six and 24hours. Keeping the AHA guidelines (MAP <130mmHg) in mind, a study was designed in 2006 that recruited 29 patients.36 These patients were treated with intravenous nicardipine, to maintain more even and effective reduction of blood pressure (See Figures 2 and 3). The study demonstrated that 86% of patients tolerated nicardipine, neurological deterioration was observed in 13% of patients and haematoma expansion was seen in 18% of patients.

Current Clinical Trial

The Antihypertensive Treatment of Acute Cerebral Haemorrhage (ATACH) trial37 is designed to determine the tolerability of the treatment as assessed by achieving and maintaining three different SBP goals with intravenous nicardipine infusion for 18–24 hours post-ictus in subjects with ICH who present within six hours of symptom onset. The neurological deterioration during the treatment and any serious adverse events will also be monitored. The patients are being recruited if they have initial SBP greater than 200mmHg. The study is divided into three tiers: in the first tier the SBP is kept between 170 and 200mmHg; in the second tier between 140 and 170mmHg; and in the third tier between 110 and 140mmHg. The study will be the largest of its kind and will be able to help increase our understanding of the principles of blood pressure control in acute ICH. Currently, we use AHA guidelines to maintain MAP between 90 and 130mmHg at our institution with intravenous nicardipine infusion using our protocol (see Figure 4).

Initiation of Oral Antihypertensive Medications

Twenty four hours after ICH, patients should be maintained at intermediate levels (below 160/100) as high proportion of the ICH patients have chronic hypertension by the use of oral antihypertensive medications. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure provides a new guideline for hypertension prevention and management. The following are the key messages:

a) In persons older than 50 years, SBP of more than 140mmHg is a much more important cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factor than diastolic BP.

b) The risk of CVD, beginning at 115/75mmHg, doubles with each increment of 20/10mmHg; individuals who are normotensive at 55 years of age have a 90% lifetime risk for developing hypertension.

c) Individuals with a SBP of 120–139mmHg or a diastolic BP of 80–89mmHg should be considered as prehypertensive and require health-promoting lifestyle modifications to prevent CVD.

d) Thiazide-type diuretics should be used in drug treatment for most patients with uncomplicated hypertension, either alone or combined with drugs from other classes. Certain high-risk conditions are compelling indications for the initial use of other antihypertensive drug classes (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin-receptor blockers, β-blockers, calcium channel blockers).

e) Most patients with hypertension will require two or more antihypertensive medications to achieve goal BP (<140/90mmHg, or <130/80mmHg for patients with diabetes or chronic kidney disease);

f) If BP is more than 20/10mmHg above goal BP, consideration should be given to initiating therapy with two agents, one of which usually should be a thiazide-type diuretic”.38 ■