Although not life-threatening, the disorder can lead to severe persistent pain and disability. Moreover, the unpredictable nature of dystonia, with symptoms fluctuating or stabilizing for a period of time, can have a profound impact on the patient’s quality of life that is comparable to that seen in multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, and stroke.5,6

Because the pathophysiology of dystonia remains unclear, pathogenesistargeted treatment remains elusive. Thus, current treatment strategies are focused on symptomatic intervention, with the aim of relieving functional impairment, reducing pain, and improving quality of life. This short review discusses the current considerations in the management of focal dystonia, with a focus on the most common adult form of focal dystonia—cervical dystonia.

Diagnosis and Classification of Focal Dystonias

Dystonia is a hyperkinetic disorder. However, distinguishing focal dystonia from other hyperkinetic movement disorders can often be challenging, as it may be a clinical manifestation of many treatable neurological conditions such as Wilson’s disease, hypoxic or traumatic brain injury, or Parkinson’s disease. The clinical characteristics of dystonia—such as repetitive and stereotyped contractions with involvement of the same group of muscles—help to differentiate dystonia from other hyperkinetic movement disorders. For example, a patient with cervical dystonia with involuntary right-head rotation will continue to have right-head rotation throughout the course of the disorder. In contrast, choreic movements such as tics involve brief and intermittent movements. Additionally, dystonia can often be associated with tremor, which may make the diagnosis more difficult. The management of the various forms of dystonia can vary depending on the form of dystonia exhibited. Therefore, it is therapeutically important to distinguish between the various types.

Anatomical Classification

Anatomically, dystonia can be classified as focal, segmental, multifocal, generalized, or hemidystonia.

• Focal dystonia is restricted to a single, specific part of the body. The most common form of focal dystonia is cervical dystonia, which can be further classified by posture and positioning: torticollis (neck rotation); anterocollis (head forward flexion or pulled forward); retrocollis (head posterior extension or pulled backward); or laterocollis (head tilt or lateral flexion).7 Local limb dystonias can often begin as action or taskspecific dystonias such as writer’s cramp dystonia or musician’s dystonia.8

• Segmental dystonia involves two or more contiguous body parts. • Multifocal dystonia involves two or more non-contiguous body parts.

• Generalized dystonia involves either both lower extremities and another body part or a single lower extremity, the trunk, and another body part.

• Hemidystonia involves an arm and leg on the same side of the body. The Etiology of Dystonia

The pathogenesis of dystonia still remains unclear. Gene mutations and other causes are have been increasingly recognized; however, the majority of patients have primary dystonia without a specific cause.10 Abnormal neurochemical transmission in the basal ganglia, brainstem, or both resulting in abnormal execution of motor control have been proposed as pathophysiological factors.11

Focal hand dystonia such as musician’s dystonia or writer’s cramp has been suggested to be a maladaptive response of the brain to repetitive performance of stereotyped and attentionally demanding hand movements.12,13 Studies in animal models found that monkeys trained to perform a repetitive hand maneuver resulted in central changes in large sensory receptive fields, significant overlap of large sensory receptive fields across adjacent digits and across glabrous and dorsal surfaces, and the persistence of digital representations across a broad cortical distance.14 This suggests that in dystonia the brain learns feedback pathways that are essentially counterproductive. The pathophysiology of cervical dystonia is thought to relate to abnormal execution of motor programs.15,16 Approximately 12% of cervical dystonia cases have a family history and women are affected twice as often as men.17,18

Current Management Options in Dystonia

Currently, treatment of dystonia is focused on symptomatic intervention with the aim of improving quality of life by reducing immediate symptoms such as movement, posture, and severity of pain. Prior to the introduction of botulinum toxin for focal dystonias, three main categories of medications were utilized in focal dystonia with limited success: benzodiazepines, anticholinergics, and antispasticity agents. Benzodiazepines—such as clonazepam, lorazepam, and diazepam—may reduce the intensity of the dystonic muscle spasms; however, their use may also be limited by sedation and cognitive side effects. Antispasticity agents—such as baclofen—may be helpful in reducing the intensity of dystonic muscle spasms, and may be particularly useful in patients who may have a dystonia associated with cerebral palsy.19 The anticholinergic agents—such as trihexyphenidyl and benztropine—are often effective, although they exhibit dose-dependent side effects of sedation, dry mouth, and reduced short-term memory.20,21

The use of botulinum toxin to treat focal dystonia and, in particular, cervical dystonia has dramatically improved the quality of life of patients with the condition, and it is now the treatment of choice for patients with cervical dystonia. Botulinum toxin has seven distinct serotypes: A, B, C, D, E, F, and G. However, the serotypes differ in their potency, duration of action, and cellular target sites. Two forms of botulinum toxin, Botox® (botulinum toxin type A, Allergan Inc.) and Myobloc® (botulinum toxin type B, Solstice Neurosciences) are available in the US for the treatment of cervical dystonia. Botox is additionally indicated for the treatment of strabismus and blepharospasm associated with dystonia.

Injections of botulinum toxins produce chemical denervation of the muscle; the clinical benefits, which include weakness and atrophy of the muscles injected, are seen within days to weeks of administration. Neuromuscular junctions undergo neuronal sprouting, with complete neuronal activity restoration occurring at approximately six months.22

The administration of botulinum toxin therapy requires a thorough understanding of the toxin, preparation of various dilutions, and practical knowledge of typical dosages and anatomy. Electromyogram-guided injection techniques may be used to increase the magnitude of benefit.23 Botulinum Toxin Type A

Botulinum toxin type A acts by cleaving the synaptosome-associated protein of 25kDa (SNAP 25).24 Several clinical trials have shown that botulinum toxin type A is safe and efficacious in the treatment of cervical dystonia, with 70 90% of patients benefiting from botulinum toxin type A therapy.25 27 In the clinical trials, the mean dose of botulinum toxin type A was between 198 and 300 units, divided among affected muscles. Botulinum toxin type A controls symptoms of cervical dystonia for 12 24 weeks, with a mean duration of effect per patient of 15.5 weeks.28 The most commonly reported clinically relevant adverse effects associated with botulinum toxin type A include dysphagia, injection site pain, neck weakness, lethargy, dysphonia, and xerostomia. These effects were temporary, but can last for weeks or months.29 Not all patients respond well to botulinum toxin type A and 5 10% become resistant to it after a number of treatment cycles due to the development of neutralizing antibodies.26 Risk factors for the development of neutralizing antibodies include high doses, short intervals between injections, booster doses, and young age.

Botulinum Toxin Type B

Botulinum toxin type B is an antigenically distinct serotype. Botulinum toxin type B specifically cleaves the synaptic vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP)/synaptobrevin.24,30 Several clinical trials have established the efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin type B in the treatment of cervical dystonia.21,31 Moreover, it has been demonstrated that botulinum toxin type B is effective at reducing the disability, pain, and severity associated with cervical dystonia in both botulinum toxin type-A-responsive and -resistant patients.31 34 The clinical benefits of botulinum toxin type B are seen within four weeks of administration and it has a median duration of action of 12 16 weeks.35 The recommended initial dose of botulinum toxin type B is 2,500 5,000 units, divided among injected neck muscles. In clinical trials, the most commonly reported clinically relevant adverse events associated with botulinum toxin type B were dry mouth, dysphagia, and injection-site pain.31 In general, these adverse events were self-limited and well tolerated, and increased with increasing dosage.31 Botulinum toxin type B offers an alternative to the problem of resistance seen with repeated use of botulinum toxin type A, although there have been reports of antigenicity with botulinum toxin type B, which may be associated with prior botulinum toxin type A resistance.36,37

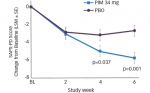

There has been only one published randomized controlled trial comparing the efficacy of botulinum toxin type A and botulinum toxin type B; this trial showed that both serotypes of botulinum toxin provide equivalent benefit at four weeks in subjects with cervical dystonia who had previously been treated with botulinum toxin type A.38 In the study, botulinum toxin type B was associated with a drier mouth. However, a longer term prospective follow-up of patients receiving an average of 10 repeated dosing sessions of botulinum toxin type B in type-A-resistant and -responsive patients revealed that patients maintained significant efficacy over time and dry mouth diminished in frequency with repeated injection.39

Conclusion

Dystonia, a debilitating neurological disorder, is still under-recognized, although the situation is improving. The pathogenesis of this spectrum of disorders remains elusive and, while the advent of botulinum toxin has dramatically transformed the symptomatic treatment of certain amenable dystonias, new therapeutics are still needed that address different modalities and associated comorbidities such as anxiety and depression. Current therapeutic options must be tailored to the needs of individual patients. The availability of two serotypes of botulinum toxins allow physicians to offer further treatment options to patients, and investigational techniques such as deep brain stimulation may address the needs of patients with generalized dystonia.