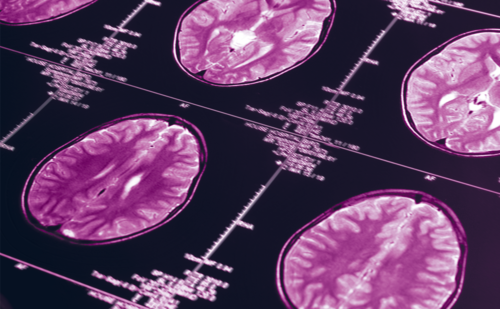

Cortical superficial siderosis (cSS) of the central nervous system is considered a rare condition, observed on gradient echo T2*- weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as a typical signal hypointensity outlining the brain surface. It is detected as a characteristic curvilinear pattern preferentially affecting the cerebral convexities.1 It reflects haemosiderin deposition in the subpial space, which cannot be removed from the subarachnoid space by the cerebrospinal fluid circulation. 2 In the population-based Rotterdam Scan Study, using a 1.5-Tesla (T) MRI, the overall incidence of SS was found to be 0.7 %, all of whom had cortical microbleeds in their vicinity. 3 It has to be distinguished from the rare classic neurodegenerative syndrome in which SS mainly affects the brainstem and cerebellum. The age of onset of this syndrome ranges from 14 to 77 years leading to death after 1 to 38 years. It is now accepted that classic SS is the result of chronic subarachnoid haemorrhage due to dural pathology or a cervical root lesion, a vascular tumour or a vascular abnormality. 4 Table 1 summarises the frequency of the most common clinical symptoms in this syndrome.

Aetiological Classification

Many disease entities can give raise to cSS: they can have a traumatic (see Figure 1) or a non-traumatic origin (see Table 1). In cSS, with a predilection for the cerebral convexity, cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) is considered as the most common cause in elderly individuals. 5 cSS is reported in 60.5 % of histologically proven cases of CAA6 and in 40 % of a clinico-radiological correlation study. 7 Some authors have even proposed to include cSS in the Boston diagnostic criteria for CAA; 4,7 however, a definite diagnosis of CAA requires a full postmortem examination.8

In our post-mortem 7.0-T MRI study with neuropathological correlates, 45 (37.5 %) out of a series 120 brains of patients with various neurodegenerative and cerebrovascular diseases were found to have SS. Although CAA was the most common cause (33.3 %) it could also be observed in brains of patients with pure Alzheimer’s disease (AD), frontotemporal lobar degeneration, Lewy body disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration and thrombo-embolic strokes. 9

Pathogenesis

The preferential aetiology is different according to the extension of the cSS. In diffuse cSS, involving more than three gyri sequels of a lobar haematoma, mainly due to CAA, is the underlying cause (see Figure 2). In focal cSS, involving fewer than three gyri cortical infarcts, due to atherosclerosis or CAA are most frequently observed (see Figure 3). They are responsible for 67 % of focal cSS compared with 33 % due to cortical microbleeds. 9 Also, in a recent study, showing that SS is a warning sign for future intracranial haemorrhage, the incidence of the concomitant occurrence of cSS and microbleeds was found to be low. 10 A possible explanation is that microbleeds in CAA brains are mainly located in the deep cortical layers and do not frequently extend up to the cortical surface. 11 On the other hand, cortical microinfarcts more frequently involve the cortical surface9 and leakage of blood develops with time, leading to some degree of haemorrhagic transformation in initially white infarcts. 12

Clinical Presentation

The symptomatology of cSS is determined by the underlying cause and disease. In diffuse cSS the clinical presentation will mainly depend on the size and the location of the underlying lobar haematoma, due to CAA. 7

Focal cSS may present as transient focal neurological episodes such as ‘aura-like’ spreading paraesthesias, visual flickering, limb jerking, limb weakness, dysphasia or vision loss. 13 These attacks are frequently recurrent and stereotyped. 14 Focal seizures and migrainous auras may also be presenting symptoms. 15

Patients with AD associated to cSS performed worse in the minimental state examination than those without cSS. 16 In a memory clinic population the incidence of cSS is higher in patients with AD than in those with mild cognitive impairment and other dementia types. 17 Also the clinical presentation of AD with cSS due to CAA is different with mainly prominent aphasia, greater than impaired episodic memory. 18

Treatment

Lipid-soluble deferiprone has been started in some classic SS trials, 19 but the drug cause significant side effects. 20 However, in cSS it is more important to treat the underlying cause than the residues of the subpial bleed. In cases of diffuse cSS the main cause will be a lobar haematoma and prior antithrombotic or anticoagulant agents should be stopped. On the other hand, one can discuss whether the observation of focal cSS should not be an indication to start with an antithrombotic drug.

Discussion

cSS should not be considered as a separate disease entity but as an epi-phenomenon of an underlying cortical pathology. When observed on MRI it could be considered as an additional argument for the clinical diagnosis of CAA, if associated to posterior microbleeds, lobar haematomas and severe white changes according to the Boston criteria. 8

In focal isolated cSS one should enlarge the possible diagnoses. Although microbleeds can now easily be detected by conventional structural MRI, cortical microinfarct detection requires 7.0-T MRI. 21 As these machines are not routinely available one can only suspect a cortical microinfarct when no microbleed adjacent to the focal cSS is observed.