Several new AEDs—felbamate, gabapentin, lamotrigine, levetiracetam (LEV), oxcarbazepine, tiagabine, topiramate, vigabatrin, zonisamide, and gabitril are currently available by prescription in the US. Over the past decade alone, 10 new AEDs have been introduced; the efficacy of the newer agents is, to some extent, similar, but the adverse effects vary. LEV has a unique mechanism of action and a favorable pharmacokinetic profile that distinguishes it from other AEDs. Long-term studies suggest higher continuation rates compared with other new AEDs. Moreover, preliminary reports are quite promising of the efficacy and tolerability of LEV against various seizure types.

Mechanism of Action

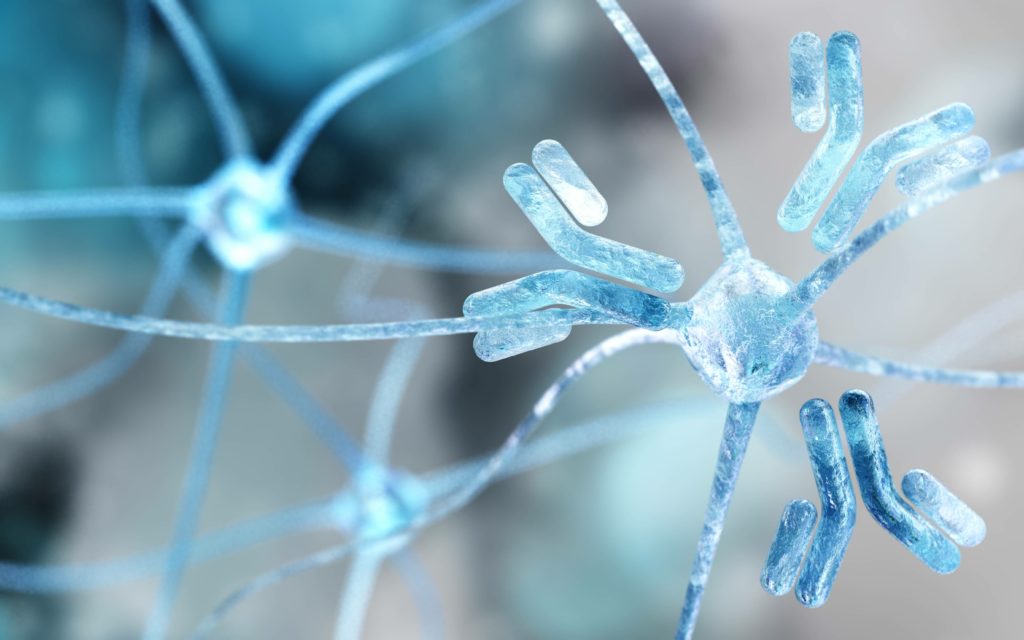

LEV has a unique pharmacological profile that distinguishes it from all the other anti-epileptic drugs. While it affords protection against seizures induced in audiogenic genetically susceptible mice as well as in electrically or pentylenetetrazol-induced kindling models, it is devoid of anticonvulsant activity in most acute animal models of epilepsy such as the maximal electroshock model.1 Its mechanism of action does not involve the classical targets of the other anti-epileptic drugs, i.e. gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) facilitation, inhibition of sodium channels, or modulation of low-voltage activated calcium channels.2 In 1995, a brain-specific binding site for LEV was described and characterized in rat brain for the first time using [3H] LEV as radioligand.3 The binding of LEV to this site was reversible, saturable, and highly stereoselective. This binding site has been identified as the SV2A protein, a protein ubiquitously distributed in the central nervous system as a component of synaptic vesicles.4 Molecular studies involving transgenic mice suggest that this protein is involved in vesicle neurotransmitter exocytosis, and that the binding affinity to SVA2 is directly proportional to seizure protection.4

Moreover, recent work has elegantly shown that recombinant SV2A protein expressed in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells and natively expressed SV2A in human brain share very similar binding characteristics in terms of ligand affinity and even binding kinetics, making the recombinant system quite suitable for use in discovery efforts to find new SV2A ligands.5 This homology between human, rat, and even mice4 SV2A increases the confidence in the results obtained in animal models of epilepsy used to evaluate compounds interacting with SV2A.

Pharmacology

Unlike other AEDs that are metabolized, the metabolism of LEV does not involve the hepatic Cytochrome P450 (CYP) system; instead, it involves hydrolysis of LEV by B-esterases in the blood to produce three pharmacologically inactive metabolites. Its elimination is reduced by 35–60% in patients with renal dysfunction.6

Since LEV is neither protein-bound in blood nor metabolized in the liver by the hepatic CYP system, LEV would not be expected to be involved in clinically-important plasma protein-binding interactions, or interactions by induction, or inhibition of CYP reactions. Indeed, to date, no clinically relevant pharmacokinetic interactions have been identified with LEV and the drug does not interact with digoxin, warfarin, or the oral contraceptive pill.7 A more recent pharmacokinetic study has confirmed the impression of little interaction between LEV and carbamazepine, phenytoin, valproic acid, lamotrigine, gabapentin, phenobarbital, or primidone.8 All of these features make LEV an ideal drug to choose for patients with seizure disorder with other comorbid conditions requiring multiple other medications. Elderly patients, for example, will be ideal candidates, given the average number of medications they take on a daily basis.9 According to the newly reported Keeper TM trials, a median overall reduction in seizure frequency of 80.1% was observed in 78 patients aged ?65 yrs with very encouraging responder rates: 76.9% of patients were ?50% responders and 40% were seizure-free.10

Recently, an intravenous (IV) formulation of this drug became available for use in epilepsy patients with partial-onset seizures, when oral administration is temporarily not feasible.A recent study showed that the injectable formulation of LEV administered IV (1,500mg infused over 15min) is bioequivalent with 1,500mg given as three 500mg oral tablets and is welltolerated in healthy subjects. LEV administered by IV infusion at dosages and/or infusion rates higher than those proposed was well tolerated in healthy subjects, and the pharmacokinetic profile was consistent with that for oral LEV. The availability of an injectable formulation of LEV for IV administration that is welltolerated and exhibits similar pharmacokinetics to oral formulations could be beneficial for patients with epilepsy receiving LEV therapy who are temporarily unable to take oral medication and therefore broadens its clinical application.11 LEV could also be a potential choice of therapy for the management of status epilepticus, even though it is not approved for that indication yet.

Clinical Efficacy and Tolerability

The short-term efficacy of LEV as add-on therapy in epilepsy patients with pharmacoresistant partial seizures was demonstrated in several studies. A recent work has shown that add-on therapy with LEV is associated with a fast, strong anticonvulsant effect within two days of treatment initiation.12 This time window of the onset of action of LEV has been verified by a recently published study that was carried out in more than 800 patients.13 This finding was also supported by a recently finished clinical trial involving a large scale of sample size.7

On the other hand, a small number of studies have addressed long-term continuation rates in a large group of patients in a clinic setting. A recent work involving a large cohort of patients with refractory chronic epilepsy attending a tertiary referral centre has demonstrated LEV to be either better tolerated or more efficacious, or both, compared with other new AEDs, such as lamotrigine and topiramate.14 A total of 811 patients (aged 14–79 years) who were initiated on LEV between November 2000 and October 2002 were evaluated; the longest duration of follow-up was 41 months (>3 years). LEV treatment was both effective and well-tolerated, with 11% of these ‘refractory’ patients becoming seizurefree after LEV treatment.

Indications of Use

LEV is currently licensed (Keppra, UCB Pharma) as adjunctive therapy in the treatment of partial onset seizures with or without secondary generalization. Therapeutic doses in adults range from 250mg daily to at least 1,500mg twice daily.15 This indication was based on the results of three multicenter, randomized, doubleblind, placebo-controlled trials, including a total of 904 patients with refractory partial seizures with or without secondary generalization for a period of at least two years.16-18 The combined results from these studies provide robust evidence for a dose-related efficacy.The drug is generally well-tolerated with discontinuation rates ranging between 7% and 13%. The range of adverse effects reported in these trials included dizziness, somnolence, asthenia, headache, behavioral problems, depression, and psychosis.19

Although not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for this indication, several open label studies have demonstrated LEV efficacy as monotherapy in newly diagnosed epilepsy and in patients with difficult to control partial epilepsy.20 Moreover, a recent phase III, randomized, doubleblind, non-inferiority design study has shown LEV to be as effective as carbamazepine controlled-release (CBZ-CR) in achieving six-month and one-year seizure freedom in newly diagnosed patients with partial onset or generalized tonic-clonic seizures.21 As a matter of fact, LEV is now approved as monotherapy in Europe. This shows that the FDA (and other agency) indications are narrow and may not need to be followed strictly; off-label use is not only acceptable, but is part of the practice of medicine. In fact, to our knowledge, a meticulous review of the literature proves that there is no AED that works in combination therapy but not in monotherapy. The concept of broad-spectrum AEDs is, sadly, not well recognized by most neurologists. A retrospective study of patients with confirmed diagnosis of idiopathic generalized epilepsy (IGE) showed that 70% of these patients at the time of referral to an epilepsy center were taking a narrow-spectrum, ill-advised AED, such as phenytoin, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, gabapentin, or tiagabine.22 On the other hand, there are a growing number of reports and speculation that LEV may be a broad-spectrum AED with efficacy for both primary generalized and focal (partial) epilepsy, and idiopathic, as well as symptomatic myoclonic epilepsy. LEV is probably the best new AED in the treatment of IGE. Clinical experience in open-label studies and anecdotal case reports suggest that LEV is effective in treating several forms of generalized seizures in adults and children, including myoclonic, absence, and primarily generalized seizures.23 As a matter of fact, LEV may replace valproate for the treatment of these disorders because of its high and sustained efficacy, fast action, and an excellent safety profile.24 A few case reports and small case groups’ studies have demonstrated a good efficacy of LEV in patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) unresponsive to conventional AEDs (valproate, lamotrigine) with more than 50% of patients becoming seizure free. Recently, class I preliminary data from a multicenter, doubleblind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial evaluating LEV as add-on treatment in refractory idiopathic generalized epilepsy with myoclonic seizures showed a 21.3% and a 3.4% seizure-free rate associated with LEV therapy and placebo, respectively.25 Just recently, LEV has been approved as adjunctive therapy in patients with JME in the US.To date, LEV is the only new AED with established efficacy in electroencephalogram (EEG) and clinical photosensitivity.26,27 LEV reduces or eliminates both the photoparoxysmal responses and the myoclonic jerks elicited by intermittent photic stimulation.27 Long-term use of LEV in some visually sensitive patients has demonstrated a good suppression effect for over four years; discontinuation of the drug before pregnancy has resulted in a return of myoclonic jerks and an increase of intermittent photic stimulation sensitivity.28

On the other hand, placebo-controlled trials in IGE are few, and, in some, there are no comparator groups and the diagnostic criteria are sometimes unclear. In fact, AED generally have indications for seizure types rather than syndromes, which may be unfortunate.The International League Against Epilepsy explicitly recommends that the classification of syndromes be “used daily in communication between colleagues” and be the “subject of clinical trials and other investigations”.29 Yet the official labeling of AED does not mention any epilepsy syndromes, much less specific types such as IGE. Recently, results of a multicenter, double-blind placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of LEV in IGE has been presented, reporting efficacy and good tolerability of doses of up to 3,000mg daily used as adjunctive treatment.25 Fifty-eight per cent of patients in the LEV arm responded with a >50% improvement in seizure control, compared with 23% in the placebo arm. Similarly, other studies have reported good or excellent therapeutic responses in patients with IGE. In one study, patients with refractory epilepsy were randomized to receive LEV 2,000mg/day, 4,000mg/day, or placebo as adjunctive therapy without titration.30 Forty-two per cent of them were suffering from IGE, although the syndromic classification was not provided. Median reduction in seizures was 66% in those with IGE receiving LEV 2,000mg/day, and 35% became seizure free for at least three months. Moreover, LEV has a potent antimyoclonic effect, even in severe myoclonic epilepsies, such as postanoxic myoclonus and Unverricht-Lundborg disease.31,32

Finally, quality of life as an outcome measure is as important as seizures responders rates in patients treated with new AEDs. The US pivotal phase III trial used Quality of Life in Epilepsy-31 (QOLIE-31) battery in 246 patients treated with LEV.16 As a result, cognitive functioning and overall QOL scores improved significantly, compared with placebo.33

In conclusion, LEV is a new AED with a unique mechanism of action. Its favorable side effects profile makes it an ideal choice for special population. It is generally well-tolerated, with rapid onset of action. Moreover, it appears to extend its antiseziure activity for extended periods. It is probably one of the best new AEDs that have a broad spectrum of activity against mutable seizure types