Dystonia is characterized by involuntary muscle contractions causing twisting movements and abnormal postures.1 It is clinically and etiologically heterogeneous and is most usefully classified by etiology as either primary or secondary dystonia. In primary dystonias, dystonia is the only neurologic sign (except for tremor), and there is no evidence of an acquired cause or of any neurodegenerative process. In secondary dystonias, dystonia occurs together with other neurologic symptoms and is due to acquired causes or to neurodegenerative disease. An intermediary category is termed ‘dystonia plus syndromes,’ and consists of disorders in which there is no acquired etiology or neurodegeneration, but in which there are neurologic symptoms other than dystonia.

This category includes dopa-responsive dystonia (DRD/DYT5), myoclonus dystonia (MD/DYT11) and rapid-onset dystonia-parkinsonism (RDP/DYT12) (see Table 1: Classification of Dystonia). Primary dystonia is subdivided into early-onset and adult-onset forms. Early-onset primary dystonias typically initially affect a limb and subsequently spread, frequently becoming generalized. Genes have been identified in two forms of early-onset primary dystonia: DYT1 and DYT6. Late-onset primary dystonia typically occurs in either cervical, cranial, or brachial muscles, and remains focal or segmental. Adult-onset focal dystonia (with cervical dystonia as the most common form) is far more common than early-onset primary dystonia.

Although the pathophysiology of dystonia remains incompletely understood, advances in two major areas of research over the past two decades have led to important insights into mechanisms of dystonia. First, with the identification of dystonia genes, investigations using cellular and animal models of dystonia have become possible. In addition, clinical studies can take advantage of the reduced penetrance in primary dystonia, whereby only approximately 30% of gene mutation carriers manifest dystonia, by performing clinical investigations in dystonia patients (manifesting carriers) as well as in gene carriers without dystonia (non-manifesting carriers), providing insight into the question of which abnormalities are inherent to the gene mutation (endophenotypes or trait features) regardless of clinical status versus which abnormalities occur in association with clinical dystonia. Second, advances in functional neuroimaging have led to the possibility of in vivo identification of distinct functional, anatomic, and neurochemical abnormalities in dystonia patients and in non-manifesting gene carriers.Historically, the principal cause of dystonia has been thought to be dyfunction of the basal ganglia, which arose from the concept of the basal ganglia as the brain region responsible for integrating motor control, together with the fact that secondary dystonia is most commonly due to lesions of the basal ganglia, specifically the putamen or globus pallidus. However, the absence of neurodegeneration in primary dystonia, as well as observations that lesions of brain regions other than the basal ganglia can lead to secondary dystonia, have led to the concept of dystonia as a neuro-functional disorder, i.e. a disorder characterized by abnormal connectivity that may occur in a structurally normal appearing brain. Dystonia symptoms may occur, then, due to developmental abnormalities resulting in synaptic dysfunction or increased plasticity of motor circuits; dystonia is therefore considered to be a motor system disorder rather than a disease of a particular motor structure. Accordingly, studies using various investigative tools have yielded evidence of dysfunction in almost every region of the central nervous systm (CNS) involved in motor control and sensorimotor integration, including cortex, brainstem, cerebellum, and spinal cord.2–4

Genetic and Molecular Mechanisms

Primary Dystonias

Early-onset Torsion Dystonia

Early-onset torsion dystonia (DYT1) is a childhood-onset disease with a mean age of onset of 12 years and onset before age 26 years in almost all clinically ascertained cases, although onset up to age 64 years has been reported. It typically first affects a limb and in approximately 65% of patients progresses over 5–10 years to generalized or multifocal dystonia. It does not commonly affect cranial muscles. It is caused by an in-frame GAG deletion in exon 5 of the DYT1 (TOR1A) gene, which results in the loss of a glutamic acid residue in the C-terminal region of the protein. The mutation is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern with reduced penetrance of approximately 30%. The reason for reduced penetrance is not known, but it is likely a result of both genetic and environmental factors. Risch et al. identified the first evidence of an intragenic modifier of DYT1 dystonia penetrance, demonstrating a protective effect of the 216H allele in trans with the GAG deletion.5

The precise role of TorsinA, the protein encoded by the DYT1 gene, remains unknown. It is a member of the AAA+ family of proteins (ATPases associated with a variety of cellular activities), chaperone proteins that mediate conformational changes in target proteins and perform a variety of cellular functions. TorsinA is widely distributed in the brain, with intense expression in the substantia nigra dopamine neurons, cerebellar Purkinje cells, thalamus, globus pallidus, hippocampus, and cortex.6–10 It is restricted to neurons in the brain and in the normal state it localizes to the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum. Current evidence, including studies using DYT1 patient fibroblasts, indicates that mutant torsinA likely leads to dysfunction of the endoplasmic reticulum and nuclear envelope, resulting in abnormalities in nucleo-cytoskeletal connections and/or protein processing through the secretory pathway.11

Early-onset Torsion Dystonia Animal Models

Two types of mouse models of DYT1 have been produced: heterozygous knock-in mice, in which the GAG mutation is introduced into the endogenous mouse torsinA gene, and transgenic mice, in which the human mutant torsinA gene is inserted into the mouse genome and over-expressed via genetic promoters. Neither of these models has overt dystonic features, although they both manifest more subtle motor abnormalities, including hyperactivity and deficits in beam walking.12,13

Another transgenic mouse model has impaired motor-learning in a similar fashion to14 motor sequence learning deficits found in DYT1 non-manifesting carriers.15 Mice that are either homozygous knock-in or knock-out for the mutation die at birth, whereas a knock-down mouse model in which expression of torsinA is reduced has a phenotype similar to the heterozygous knock-in mice.16 This suggests that the pathogenic deletion produces a loss of function of TorsinA. The loss of function may be the result of a dominant negative effect, in which the mutant protein interferes with the wild-type protein.DYT6 Dystonia

DYT6 dystonia is characterized by a relatively early but broad age of onset (mean 16 years, range five to 49 years). The body regions first affected include the arm, cranial muscles (larynx, tongue, and facial muscles), and neck. In contrast to DYT1, onset at the leg is uncommon. The dystonia usually progresses, but the degree of progression is variable. For most patients with DYT6 dystonia, disability is due to cranial and cervical dystonia, including significant speech difficulties. As in DYT1, DYT6 is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern with reduced penetrance. The DYT6 gene, THAP1, is the most recently identified dystonia gene.17 The initial report was of two mutations in the THAP1 gene causing DYT6 dystonia in five families. Subsequent genetic screening studies in families with early-onset, non-DYT1, non-focal primary dystonia identified 11 additional THAP1 mutations in families of diverse ancestries, suggesting that mutations in THAP1 may underlie a substantial proportion of dystonia in early-onset non-DYT1 families, particularly in those with affected cranial muscles.18,19 The THAP1 protein is a sequence-specific DNA binding factor that regulates cell proliferation through modulation of target genes. Mutated THAP1 may disrupt DNA binding, resulting in transcriptional dysregulation, although how this disrupts brain function leading to dystonia remains unknown. Determining the specific pathogenic mechanisms of THAP1 mutations and their import in other dystonia populations are important future research goals.

Dystonia Plus Syndromes Dopa-responsive Dystonia

The classic form of dopa-responsive dystonia (DRD/DYT5) is an early-onset dystonia presenting in childhood (five to six years of age) with dystonia of the lower extremities, and a diurnal pattern to the symptoms. Arm dystonia, hyperreflexia, and parkinsonism are other common features. The hallmark feature of this disorder is a dramatic and sustained resolution of dystonia symptoms in response to low-dose levodopa therapy. The autosomal dominant form of DRD is caused by mutations in the GCH1 gene. GCH1 is required for the synthesis of tetrahydrobiopterin, an essential cofactor for tyrosine hydroxylase, which is the rate-limiting enzyme in dopamine synthesis. Penetrance is incomplete and is gender related, with females manifesting dystonia two to four times more frequently than males.20 Over 100 different GCH1 mutations have been identified,21 but GCH1 mutations are not found in approximately 25% of patients with DRD.22 Recessive genetic causes account for some of the mutation negative cases, but a small proportion of DRD cases remain unexplained.22

There are several autosomal recessive forms of DRD to be found, which are due to varying mutations in genes encoding other enzymes involved in dopamine synthesis, including tyrosine hydroxylase (TH),23 6-pyruvoyltetrahydropterin synthase (6-PTPS),24 and sepiapterin reductase.25 Typically, the clinical picture in these conditions is different from GCH1 DRD, with infantile-onset severe neurologic symptoms, including hypotonia, severe bradykinesia, drooling, ptosis, miosis, oculogyria, cognitive impairment, and seizures.22 Another important autosomal recessive cause of the DRD phenotype are mutations in the ‘juvenile’ parkinsonism parkin gene.22,26,27 Generally the presence of early prominent parkinsonism and severe dyskinesias favors parkin mutations.Myoclonus Dystonia

Myoclonus dystonia (MD) (DYT11 and DYT15) is characterized by prominent early-onset myoclonus with or without dystonia. Symptom onset is typically in the first or second decade, and symptoms tend to plateau in adulthood. The neck and arms are the most commonly involved sites, followed by the trunk and bulbar muscles, and, least commonly, the legs.28 The myoclonus may improve dramatically with alcohol. Psychiatric symptoms, including anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder appear to be increased in MD family members.29,30 MD is caused by dominantly inherited mutations in epsilon-sarcoglycan (SGCE). All forms of SGCE mutations have been identified, including missense, nonsense, deletions, and insertions. The gene is maternally imprinted, so most individuals who inherit the gene from their father manifest symptoms, whereas those who inherit the gene from their mother are usually unaffected. SGCE is one of five known members of the sarcoglycan gene family, which encode components of the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex (DGC). Recessive mutations in the other sarcoglycan genes cause various forms of muscular dystrophy, none of which include dystonia (and patients with MD do not have muscular dystrophy). SGCE mutations do not account for all familial MD and are probably are not responsible for most sporadic MD cases. Only about 50% of those with a family history and 10–15% of sporadic cases are found to have mutations (Raymond and Ozelius 2009, gene clinics update). One other gene locus for MD has been mapped to chromosome 18p in one family (DYT15).31

Rapid-onset Dystonia-Parkinsonism

RDP (DYT12) is a rare disorder that is characterized by both dystonia and parkinsonism. It is usually sudden and rapid in onset, evolving over hours to days. The disorder usually begins in childhood or early adulthood, and can sometimes be associated with environmental triggers of emotional or physical stress. Motor features may include dystonia–parkinsonism–hyperreflexia or dystonia alone. The dystonia is characterized by prominent bulbar features of dysarthria and facial grimacing. Limb dystonia is usually tonic, with relatively sustained limb posturing. The parkinsonian features of bradykinesia, with waxy, effortful movements and postural instability are prominent. Seizures, depression, and social phobia have also been reported. After the initial onset or period of worsening, symptoms tend to plateau or can sometimes improve and, occasionally, after a more insidious onset there may be a sudden worsening.32,33 The gene has been identified as ATP1A3, which codes for the sodium potassium transporting34 ATPase alpha-3 chain, a catalytic subunit of the sodium-potassium pump.35 Inheritance is autosomal dominant with reduced penetrance, and de novo mutations have been observed. At least six missense mutations have been identified; structural modeling and cell studies indicate that they are loss-of-function mutations that impair enzyme activity or stability. ATP1A3 is expressed in neurons in the CNS although it is found in peripheral cell types as well. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) homovanillic acid (HVA), a dopamine metabolite, is reduced in some patients, but neuroimaging and pathology do not suggest nigral degeneration, and RDP is generally refractory to treatment, including levodopa.

Neurophysiologic Mechanisms— Impaired Inhibition, Abnormal Sensory

Processing, and Abnormal Plasticity

In conjunction with investigations into the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in genetic forms of dystonia, clinical studies in patients with various forms of dystonia and in non-manifesting gene carriers have explored a variety of neurophysiologic abnormalities in dystonia. The primary neurophysiologic mechanisms considered to be important in dystonia pathogenesis include decreased cortical inhibition, increased cortical excitability, abnormal sensory processing, and maladaptive cortical plasticity. Evidence of these abnormalities has been demonstrated across various levels of the sensorimotor circuit.

A role for abnormal sensorimotor processing and maladaptive cortical plasticity in dystonia pathogenesis is suggested by several clinicalphenomena in which dystonia occurs (or, in the case of sensory tricks, improves) in association with an alteration or disturbance in sensorimotor feedback. Examples include occurrences of task-specific dystonias such as writer’s cramp and musician’s dystonia in the setting of highly repetitive motor tasks; peripheral trauma causing dystonia at the affected body part; blephorospasm occurring after dry eyes or eye irritation; and the phenomenon of sensory tricks improving dystonia symptoms. Furthermore, in studies on monkeys, highly repetitive and stressful hand movements led to abnormal hand movements similar to dystonia and to degradation of the receptive fields corresponding to the hands in the primary sensory cortex.36,37 Early neurophysiologic investigations of sensorimotor processing in dystonia that took place included electroencephalographic (EEG) and magnetoencephalographic (MEG) studies of evoked responses in the somatosensory cortex of patients with focal hand dystonia, which found a less segregated representation of the individual digits in the somatosensory homunculus in these patients compared with non-dystonic subjects.38,39 Studies of sensory processing in dystonia patients using spatial discrimination thresholds (SDT) or temporal discrimination thresholds (TDT) (tests of discrimination between two close-interval sensory stimuli) have found abnormal SDTs and TDTs in patients with adult-onset sporadic primary dystonia and in their unaffected relatives.40,41 Notably, a recent study comparing SDT and TDT as potential endophenotypes found that TDT was a much more reliable measurement.42

‘Double pulse’ repetitive transmagnetic stimulation (rTMS) studies have demonstrated evidence of decreased cortical inhibition and increased excitability in various forms of dystonia, including in both DYT1 dystonia patients and DYT1 non-manifesting carriers,43 and in the hand motor cortex in both focal hand dystonia patients as well as in patients with blephorospasm.44 Interestingly, in two TMS studies in patients with psychogenic dystonia, the abnormalities of cortical inhibition seen in patients with organic dystonia were also seen in the psychogenic dystonia patients.45,46

rTMS studies are also used as probes of cortical plasticity in dystonia. In these studies, conditioning protocols are used that produce long-term changes in cortical excitability, i.e. either decreased or increased excitability, depending on the frequency of the repetitive pulses. Motor excitability is assessed by measuring the EMG response to a standard single TMS pulse before and at various times after the plasticity-inducing protocol. These studies have found evidence supportive of aberrant plasticity in patients with various forms of dystonia, including focal hand dystonia and in DYT1 manifesting and non-manifesting carriers.47,48 For example, in a paired associative stimulation (PAS) protocol, a stimulus to the median nerve is paired with a subsequent TMS pulse to the contralateral hand motor cortex. have found reduced D2 binding in the caudate and putamen.61,62 Similar findings were seen in DYT1 non-manifesting carriers, indicating that the dopamine-related abnormalities do not directly cause dystonia.

Acetylcholine

A central role for cholinergic dysfunction in dystonia pathogenesis is suggested by the observation that anticholinergic medications are the most effective pharmacologic agents in improving dystonia symptoms in primary dystonia patients. In studies in torsinA transgenic mice, Pisani and colleagues have found evidence of abnormal cholinergic transmission, with a paradoxical excitation of cholinergic interneurons in response to activation of D2 receptors rather than the normal response of inhibition of firing activity that likely leads to enhanced acetylcholine release.63 More recently, they further investigated the hypothesis that this abnormal cholinergic tone could disrupt synaptic plasticity in this DYT1 mouse model, and using cross-clamp electrophysiologic recordings found evidence of altered corticostriatal synaptic plasticity, and then further demonstrated that with pharmacologic normalization of striatal acetylcholine, normal plasticity could be fully restored in the transgenic mice.

Conversely, when acetylcholine was pharmacologically increased, the plasticity abnormalities were seen in mice expressing normal torsinA and in non-transgenic controls. These findings support the notion that unbalanced cholinergic transmission plays a pivotal role in the abnormal synaptic plasticity of DYT1 dystonia, and also provide a clue to the ability of anticholinergic drugs to improve dystonia symptoms.64

Gamma-aminobutyric Acid

Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter and is also important in shaping plastic responses of the CNS to somatosensory and other stimuli, including the maintenance and plasticity of cortical receptive fields. Drugs that potentiate GABA, such as benzodiazepines and baclofen, are modestly effective against dystonia symptoms. In animal studies, application of the GABA antagonist bicuculline to the motor cortex of monkeys produces abnormal movements similar to task-specific dystonia.65 Studies measuring GABA levels in the cortex and striatum of patients with adult-onset primary dystonia found decreased GABA levels in cortical and subcortical regions contralateral to the dystonic limb.66Treatment of Dystonia Pharmacologic Treatment

The medications that are most effective in the treatment of dystonia include anticholinergics (trihexyphenidyl), GABA agonists (baclofen and benzodiazepines), and dopaminergic agents. The effectiveness of these classes of drugs is consistent with the findings discussed above of alterations in dopminergic and cholinergic neurotransmission and reduced GABA-mediated inhibition in the dystonic CNS. Trihexyphenidyl is the first-line medication for treatment of childhood-onset primary generalized or segmental dystonia. Focal dystonia can be effectively treated with botulinum toxin injections. The toxin blocks the vesicular release of acetylcholine into the neuromuscular junction, causing temporary local chemodenervation and muscle weakness, reducing the excessive activity of the affected dystonic muscles. Botulinum toxin is the first-line treatment for cervical dystonia and blephorospasm, and is also frequently used to treat laryngeal dystonia (spasmodic dysphonia), and focal limb dystonia. Aside from its direct peripheral effect of weakening affected muscles, botulinum toxin injections may also reduce afferent feedback from affected muscles, potentially normalizing the abnormal plastic changes in the CNS. Accordingly, DTI studies have shown normalization of white-matter abnormalities after botulinum toxin treatment in some dystonia patients,67 and in TMS studies in cervical dystonia patients treated with botulinum toxin, abnormalities in hand motor cortex were reversed.68

Neurosurgical Treatment

Historically, dsytonia patients were treated surgically with pallidotomy or thalamotomy. These lesional surgeries provided significant benefit to dystonia symptoms in some cases, but also frequently caused permanent, disabling side effects, particularly dysarthria. Lesional surgeries have now been replaced by deep brain stimulation (DBS), which mimics a lesional effect but is reversible and adjustable. In the past two decades, DBS has come to the forefront as an important treatment option for patients with severe medically refractory primary dystonia. The current accepted target in DBS for dystonia is the globus pallidus (Gpi). DBS is thought to generate its clinical effect by inducing functional changes within the abnormal motor networks in dystonia and ultimately normalize pathologically overactive motor activation responses. In contrast to the rapid effect of DBS that occurs in Parkinson disease or essential tremor, the effect of DBS is typically delayed in dystonia, frequently taking weeks to months, consistent with the concept of dystonia as a disorder of sensorimotor connectivity that requires time to reorganize and accommodate changes along the entire motor circuit after DBS.

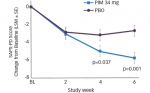

Two prospective, double-blinded, controlled trials of pallidal DBS in primary dystonia have been completed, with both demonstrating that it significantly reduces dystonia symptom severity and functional disability and improves quality of life.69,70 However, there is a distinct variability in the response to DBS among dystonia patients, with some patients showing dramatic improvement whereas others benefit only modestly or not at all, and no single factor, including DYT1 gene status, has been found to be clearly predictive of response. A retrospective analysis found lack of fixed skeletal deformity, shorter duration of disease, and younger age at surgery to be the strongest predictors of response. The question of which patients with primary dystonia will have the best response to DBS therefore remains open and requires further investigation.

In secondary dystonia, data regarding the efficacy of DBS is scant and, with one recent exception, consists only of case reports or small cohorts with heterogeneous forms of secondary dystonia, with results ranging from no benefit to dramatic improvement. Most recently, Vidailhet et al. reported a multicenter prospective pilot study of bilateral pallidal DBS in 13 adults with dystonia-choreoathetosis cerebral palsy, and the response in these patients was again heterogeneous.71 The question of whether DBS should be considered as a treatment option for secondary dystonia therefore also remains open.

In conclusion, dystonia is a neurofunctional disorder characterized by alterations at various levels and at multiple points along the sensorimotor circuit. Multiple causes can cause these disruptions and lesions along different points in interconnected pathways can yield similar motor dysfunction. Although the basal ganglia is clearly a crucial brain region, abnormalities exist in many other regions throughout the motor circuit. The existence of dystonia endophenotypes in genetic forms of dystonia, i.e. abnormalities related to the gene mutation regardless of clinical manifestation of dystonia, suggest that it may be a ‘second hit’ disorder in which genetically predisposed brains can be thrown into an unbalanced dystonic state by environmental or genetic factors. Major challenges for future investigations include searching for common molecular pathways among the various genetic dystonias, production of an animal model that manifests a clearly dystonic phenotype, exploration of the question of the extent to which the identified mechanisms in the genetic primary dystonias are involved in the more common primary focal dystonias or secondary dystonia, further exploration of which neurophysiologic or metabolic abnormalities are true endophenotypes and which are related to clinical penetrance of dystonia, and further investigation of the basic question of how the cell biologic effects of the identified mutant proteins translate into the motor systems-level effects that result in clinical dystonia. Ultimately, a more complete understanding of the pathophysiology of dystonia should lead to better, more rational, targeted therapies.