Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is a sensorimotor condition that primarily results in sleep disruption and subsequent daytime functional symptoms, particularly for those individuals with moderate-to-severe cases. In recent years there has been a shift from using the name ‘Restless Legs Syndrome’ to using ‘Willis–Ekbom Disorder’ (WED), in order to address matters of stigma and title inaccuracy.

The currently accepted clinical diagnostic criteria for RLS (WED) are: 1) an urge to move the legs, usually accompanied by an uncomfortable sensation(s); 2) the uncomfortable sensation(s) begins or worsens during periods of rest; 3) the unpleasant sensations are partially or totally relieved by walking/movement; and 4) the urge to move is greater in the evening or night than during the day.1Recently, a fifth criterion has been added: the disorder cannot be accounted for as symptoms primary to another medical or behavioural condition.2,3 This helps differentiate RLS (WED) from other disorders that mimic the symptoms of RLS (WED). Mimics, such as leg cramps, peripheral neuropathy, radiculopathy, arthritic pain and positional discomfort, may make the diagnosis of RLS (WED) difficult3 or may lead to misdiagnosis, causing a negative impact on patient quality of life (QoL).

The full pathology of RLS (WED) is not yet entirely understood, but various studies have linked RLS to several neurological factors, including decreased iron content in the substantia nigra, decreased dopamine neurotransmission in the striatum and increased glutamate levels in the thalamus.4–6 RLS symptom severity can fall across the entire clinical spectrum ranging from mild, moderate, severe, to very severe; it is usually determined by frequency and severity of symptoms, in addition to its impact on patient QoL.7

Understanding QoL has been a topic of growing interest over the past few decades and may influence treatment options and the psychological well-being for those living with a chronic condition. Although there have been many studies investigating the diagnostic criteria, epidemiology and costs involved with RLS (WED), less attention has been paid to the cost and toll put upon the RLS patients’ QoL. Modern QoL studies tend to be multidimensional and cover physical, social, emotional, cognitive and work- and role-related aspects of patients’ lives through the use of questionnaires or interviews.8 Recent federal policy changes have illustrated the need for measuring QoL to supplement public health’s traditional measures of morbidity and mortality. To this end, Healthy People 2000, 2010 and 2020 identified QoL improvement as a central public health goal.9,10 To meet the goal of QoL improvement, QoL deficits must first be understood. A study by Abetz et al. used the Short Form 36 (SF-36) Health Survey to assess the following eight domains: physical functioning, role limitations due to physical problems, bodily pain,general health perceptions, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems and mental health.11 The authors also used a modified version of the International Restless Legs Scale-Patient Version (IRLS-PV) to assess the severity of RLS (WED) symptoms, which they categorised as mild, moderate or severe and found significantly lower SF-36 scores for RLS (WED) patients compared with the general population in all eight areas measured. Analysis of the IRLS-PV found that increased RLS (WED) severity had a significant effect on all areas of functioning, with the exceptions of physical functioning and general health. Furthermore, RLS patients had significantly lower scores in all eight domains compared with patients with hypertension, and significantly lower scores in six of the eight domains compared with patients with other cardiovascular conditions (i.e. congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, angina).11 Their data show that RLS (WED), although classified as a sleep disorder, does not affect sleep alone. This disorder has a significant influence on patients’ QoL that extends beyond sleep, affecting patients’ social lives and emotional and psychological health.

Effects on Quality of Life

Epidemiology and Quality of Life Variation

The epidemiology of RLS (WED) has been the subject of numerous studies published in the last decade, and it has been previously found that RLS (WED) prevalence may vary by region, gender, ethnicity and age.12–14 The largest of these studies, the RLS Epidemiology, Symptoms and Treatment (REST) General Population Study, surveyed 15,391 adults across the US, France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK to determine the prevalence of those with clinically significant RLS (WED) symptoms.15 The total population that met all diagnostic criteria for RLS (WED) at least once per week was found to be 5 %. Almost 3 % of participants in the study were sub-classified as ‘sufferers’ because they experienced moderately or severely distressing symptoms at least twice per week. Of those designated RLS (WED) patients, more than 75 % reported sleep-related symptoms, 59.4 % reported pain associated with their symptoms, 55.5 % reported disturbed daytime functioning and 26.2 % reported mood disturbance. Women were twice as likely as men to have RLS (WED), and 64 % of patients were 49 years of age or older.15 In addition, one population survey conducted in Korea found the prevalence of RLS to be 12.1 % – a rate higher than that of North American and European regions, indicating that RLS may be linked to region or ethnicity.16 While women generally report worse QoL compared with men for medical conditions, and RLS occurs more frequently in women than in men, previous studies in RLS have shown that there are no significant differences in RLS symptom severity in relation to gender and there are no significant RLS-QoL differences in relation to gender.17–19 Few studies have specifically been conducted evaluating prevalence of RLS among African American, Hispanic or Asian American individuals. One study found that RLS is twice as prevalent in non-African American males and four times as prevalent in non-African American females compared with African American males and females, respectively.20 No QoL data have been reported in terms of variation in QoL for RLS patients by race/ethnicity, and this gap in the literature represents a need for further investigation.

Sleep and Quality of Life

Due to its tendency to worsen at night, RLS (WED) can naturally lead to sleep disorders, such as insomnia and chronic insufficient sleep.15 Symptoms of RLS and sleep disruption have been shown to lead to impaired daytime activity and reduced QoL.21 As such, QoL deficits in RLS come primarily through sleep disturbance. Previous studies have shown that patients with more severe RLS symptoms may get as little as four to five hours of sleep per night.22,23 This disruption in sleep can lead to significant QoL deficits (i.e., cognitive deficits, mood and emotional functioning, fatigue). A French study conducted in 2001 looked at three groups recruited from the general French population: severe insomniacs, mild insomniacs and good sleepers. The authors showed, using the SF–36 QoL survey, that both severe and mild insomniacs had lower scores in eight of the nine QoL domains compared with good sleepers, with severe insomniacs being more affected.24 Other studies have shown that QoL improvement is correlated with sleep improvement in both RLS and other sleep disorders.25,26 However, clinical reports indicate that RLS patients report less sleepiness than expected for their degree of sleep loss.27 These studies suggest that RLS patients’ QoL can be affected by the clinical symptoms of their condition as well as the indirect consequences that accompany RLS (i.e., significant sleep disruption, insomnia, sleep deprivation and even the disturbance to their bed partners’ sleep quality).28

Cognition and Quality of Life

In a study conducted to evaluate the effect that RLS (WED) has on patient cognition, Pearson et al. examined the cognitive deficits associated with RLS (WED) compared with the general population. Both groups were required to complete a cognitive battery that tested cognitive functions exquisitely sensitive to sleep loss (a trail-making test, a Porteus Maze test, the Stroop word test and two tests on verbal fluency – tests chosen by the authors to assess pre-frontal cortex [PFC] functioning). It was found that RLS (WED) patients showed significant deficits on two of the PFC tests. The cognitive deficits suffered by RLS (WED) patients were similar to that of healthy subjects after one night of total sleep deprivation.29 Further studies are warranted regarding the severity and mechanisms surrounding this relationship between cognitive function and RLS because another study by Gamaldo et al. has shown the possibility of sleep loss adaptation in RLS patients, as RLS patients showed fewer cognitive deficits than matched sleep-restricted controls.23 Nonetheless both studies demonstrated related PFC functioning, which can certainly explain the potential symptoms regarding concentration, workplace productivity and overall functioning. In fact, a study by Allen et al. examined lost productivity, healthcare-resource use and expenditure reported by patients in 2007. Of the 251 participants included in the study they found that job absenteeism associated with primary RLS (WED) was 1.1 % (0.3 hours per week), 57.6 % of participants visited a primary care or general practitioner at least once in previous 3 months and 54.2 % of RLS (WED) sufferers were using at least one medication.30 Furthermore, workplace productivity loss was 19.9 % (1 full day per week), with disease severity being strongly correlated with loss in productivity.30,31

Economic Burden and Quality of Life

The effect of RLS (WED) on patients is not limited to the healthcare arena. There is a significant economic burden on RLS (WED) patients, both directly due to costs of managing the disease and indirectly due to QoL deficits from occupational matters, such as reduced productivity, absenteeism and unemployment as result of their condition.31 A study by Abetz et al. reported, from a sample of 550, that 5 % of patients were unemployed due to RLS symptoms.32 Furthermore, annual direct expenditures based on 3 months of data for participants with RLS (WED) were found to be US$350 (€259) for patients with primary RLS, and US$490 (€362) for patients labelled ‘sufferers’.30 A German study conducted in 2009 examined the cost-of-illness for patients with RLS. The authors found that annual direct costs to a ‘sickness fund’ (a type of non-profit health insurance provider that most Germans are obliged to join) were estimated to be €989 ($1,343, adjusted for inflation), while €1285 (US$1,744) in costs were incurred outside the sickness fund system for RLS patients. Drug costs represented roughly two-thirds of these expenditures.31,33 When productivity losses are accounted for, it becomes clear that RLS (WED) both directly and indirectly places a significant financial burden to both patients, families and the community.

Social Burden and Quality of Life

QoL deficits extend to patients’ social lives, including romantic and family relationships. This can cover patients’ romantic and intimate relationships, leisure activities, family life and friendships.34 In the REST general population study, as many as 28 % of RLS (WED) patients reported that their social life was affected by symptoms, their partner was kept awake by their symptoms and their personal relationships were affected.15 Furthermore, previous studies have shown the effect of RLS on patient emotional functioning (i.e., mood, depression, anxiety).34,35 The effects of RLS tend to extend past the mere ‘troubled sleep’, and patients have reported failed relationships specifically due to RLS symptoms.36 A study published by Gao et al. has previously shown that men with RLS had a higher likelihood of concurrent erectile dysfunction, which has been shown to potentially increase the risk of relationship and marital discord further.37–39

Quality of Life in Children with Restless Legs Syndrome (Willis–Ekbom Disorder)

Most of the current literature on RLS (WED) addresses the adult population and it was not before 2007 when the initial large-scale epidemiological study was reported to characterise the prevalence and impact of RLS in children and adolescents.40 According to this study, 1.9 % of children aged 8–11 years old and 2.0 % of adolescents aged 12– 17 years old are estimated to have RLS, with no significant differences in gender. Although there have yet to be studies that investigate QoL in children with RLS (WED), symptoms such as sleep disturbances are suspected to reduce QoL. Similar to adults, children who suffer from RLS (WED) also report chronic problems with sleep onset, sleep maintenance and growing pains, which may increase risk of depression and reduce QoL.41,42 Lower sleep efficiency and longer sleep latencies in 6 to 13-year-old school children were also associated with poor performance in working memory tasks, suggesting that adequate sleep quality and quantity is important for learning and cognitive processes in children.43 To this end, decreased sleep quality due to pathology (i.e., sleep apnoea) and worse sleep habits, including sleep debt and insomnia, in children and adolescents was tied to poorer academic performance.44 Other reported comorbidities associated with RLS (WED) in children, including parasomnias, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), anxiety disorders and depression, may also contribute to overall decline in QoL.41,45 Interestingly, ADHD in children has also been associated with iron deficiency, which is also found in some patients with RLS.46 In summary, further studies should be carried out to assess the impact of RLS (WED) on QoL in children.

Common Comorbid Conditions and Quality of Life

QoL deficits tend to be compounded in those with RLS (WED) who have comorbid conditions (i.e., they have pathologies that co-exist with RLS). Patients diagnosed with both RLS (WED) and comorbid conditions tend to suffer further decreases in QoL due to both conditions (see Table 1) compared with RLS alone. A variety of conditions are commonly associated with RLS (WED) including type 2 diabetes, iron deficiency anaemia, renal disease, migraines, peripheral neuropathy, sleep apnoea and multiple sclerosis.34,47–66 Patients with RLS (WED) also tend to be at greater risk of mood disorders, such as anxiety and depression. One study surveyed 3,234 participants, 103 (3 %) of which screened positive for RLS (WED) symptoms, and found that RLS (WED) symptoms severity was positively correlated with presence of anxiety and depressive symptoms.67,68 Both anxiety and depression have been shown to negatively affect relationships, work productivity and general QoL measures.69–72 Furthermore, one study showed that 34.8 % of RLS patients had suicidal thoughts compared with only 2.6 % of controls; however, the authors did not link this to severity of RLS (WED) symptoms.73 RLS (WED) patients may also be at risk of hypertension, however, the directionality of the relationship between RLS (WED) and hypertension/ cardiovascular disease still remains to be established.74–76 Despite evidence showing a clear directionality regarding this relationship, RLS patients with hypertension are still at risk of all of the complications associated with high blood pressure (i.e., ischaemic heart disease, stroke, peripheral vascular disease, heart failure, aortic aneurysms and pulmonary embolism).77–79 As such, RLS patients with hypertension suffer the same QoL deficits as RLS patients plus QoL deficits and increased mortality rate due to hypertension.80

Patients with type 2 diabetes tend to be at increased risk of RLS (WED). A study by Merlino et al. showed that of 124 patients with diabetes, 22 (17.7 %) of them had comorbid RLS (WED) compared with only 5.5 % of the control group (i.e., participants without type 2 diabetes).61 Patients with both RLS (WED) and diabetes had a greater deficit than controls in the following QoL domains: functional capacity, physical limitation, pain, social limitation and emotional limitation.34 Findings from this study suggest that patients with secondary RLS may suffer more than patients with primary RLS, as these patients suffer the QoL deficits due to RLS in addition to QoL deficits due to diabetes (or any other comorbid pathology). In addition, patients with diabetes had more hypertension and peripheral neuropathy34 that also carries an additional QoL burden.

RLS (WED) is also commonly seen in patients with iron deficiency anaemia (IDA). Allen et al. reported RLS (WED) symptoms in 23.9 % of patients with IDA. Comorbid IDA–RLS sufferers reported poorer quality of sleep, decreased sleep time, increased tiredness, and decreased energy on a sleep-vitality questionnaire.57 When compared with patients with only iron-deficiency anaemia (who did not suffer from RLS), the only QoL deficit was found in the ‘general health’ domain.56 While general health does tend to reflect a patient’s overall level of health, it should be noted that general health is only one measure on QoL surveys. This suggests that the deficits produced by the combination of these two disorders leads to a much greater decrease in patient QoL.

RLS (WED) is frequently reported in patients who suffer from migraines. A cross–sectional Dutch study showed that patients with migraines had poorer health-related QoL compared with the general population and scored worse in functioning and well-being using the RAND–36 health survey.81 Another study, performed in Germany, looked at patients suffering from both migraines and RLS (WED). Out of 411 migraine patients, 17.3 % participants met the criteria for RLS (WED). The authors found that in patients with both RLS (WED) and migraines, there is a co-association with depression – 13.6 % of comorbid patients also met the criteria for depression.82 Additionally, a study by Szentkiralyi et al. has shown that clinically relevant depressive symptoms may be a risk factor for subsequent RLS (WED).83 The effects of comorbid depression due to RLS have been discussed above, and it should be noted that these patients suffer compounded QoL deficits stemming from a combination of RLS, migraine and depression.

Current Pharmacological Treatments and Quality of Life

Pharmacological treatment for RLS (WED) is generally reserved for patients whose symptoms are frequent (several times per week) and cause moderate-to-severe discomfort.84 Several dopaminergic medications have been shown to effectively treat symptoms of RLS (WED) and have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The reduction in both RLS symptoms and sleep disturbances may result in better sleepquality and improvement in patient QoL. However, adverse side effects from these medications, including hypotension and impulsive/compulsive behaviours, may result indirectly in QoL deficits, limiting the benefit of these medications. On the other hand, treatment with non-dopaminergic medications, such as opioids, benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants and iron therapy, may also introduce undesirable side effects potentially impacting QoL negatively in RLS (WED) patients. The pharmacologic treatments of RLS and their effect on QoL are explored here.

Dopaminergic Agonists

As many studies have suggested a central role for dopamine in the pathophysiology of RLS (WED), the first lines of treatment in managing primary RLS (WED) include the FDA-approved dopamine-agonists ropinirole (ReQuip) and pramipexole (Mirapex).85,86 L-dopa (a dopamine precursor) has previously been shown to be effective at treating RLS (WED), but use of L-dopa is associated with various long-term side effects including worsening symptom severity and augmentation (a presentation unique to RLS patients treated with dopamine agonists that involves worsening symptoms despite dose escalation).87 Thus, the dopamine agonists have provided a safer alternative in treating RLS (WED) symptoms, and augmentation rates have been reported to be much lower in comparison to L-dopa.88

However, despite the effectiveness of dopaminergic medications in improving RLS symptoms, certain dopamine agonists may particularly impact QoL. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was conducted by Trenkwalder et al. to test the effectiveness of ropinirole at treating RLS (WED), and to assess QoL improvement in patients. Patients were recruited from 10 European countries (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden and the UK) and had either experienced at least 15 nights with symptoms of RLS (WED) in the previous month, or, if receiving treatment, reported they had had symptoms of this frequency before treatment.88 The study found that patients receiving ropinirole had significantly greater improvement in sleep adequacy and quantity and greater reduction in daytime sleepiness and sleep disturbance compared with the placebo group. Furthermore, ropinirole-receiving patients scored higher on disease-specific RLS (WED) QoL questionnaires, but not the general QoL questionnaire (SF-36). In this study, 16 out of 146 total participants (10.9 %) withdrew due to adverse effects. The most commonly reportedadverse effects associated with ropinirole included nausea and headache. Other ropinirole effects include orthostatic hypotension, hallucinations and sedation – all of which may have severe consequences for patients.88 For example, orthostatic hypotension has been shown to make older patients more prone to falling, and has been associated with significant morbidity and mortality.89 Hallucinations, sometimes experienced by patients taking ropinirole, may undoubtedly result in fatal consequences. Lastly, ‘sleep attacks’ due to severe and spontaneous bouts of sedation have also been linked to dopamine agonists, potentially negatively impacting QoL.90

A similar study, performed by Winkelmann et al., evaluated pramipexole use by RLS (WED) patients in the US.91 Patients with moderate-to-severe symptoms were given a dose of 0.25, 0.50 or 0.75 mg of pramipexole daily to determine drug efficacy and effect on QoL. The authors measured symptom severity and QoL, measured by the Johns Hopkins Restless Legs Syndrome Quality of Life questionnaire (RLS-QOL). Authors reported that all three doses of pramipexole were effective at decreasing symptom severity, however, the effects of pramipexole were not dose-related and effects between 0.25 mg and 0.75 mg did not differ significantly. RLS-QoL scores for pramipexole patients were significantly higher than those in the placebo group. These improvements are supported by a long-term follow-up study by Montplaisir et al. This study reported that 78 % of patients who used pramipexole for more than a year showed improvement in RLS (WED) symptoms, and that this was maintained in 96 % of those patients.86,92 However, despite improvement in RLS (WED) symptoms, the most commonly reported adverse effects of pramipexole were similar to that of ropinirole – nausea, headache, insomnia, excessive sleepiness and fatigue.91 The percentage of patients that withdrew due to adverse effects was slightly higher here than seen in ropinirole – 32 out of 258 participants (12.4 %). Previous studies have also reported headaches, insomnia/sleep disturbances and excessive sleepiness/sleep attacks, which may reduce the amount of improvement in QoL after pramipexole treatment.24,90,91 Interestingly, treatment with pramipexole has also been associated with negative effects on mood.93 Specifically, those taking pramipexole were found to have negative effects on motivation and cognition. Furthermore, another complication of treatment in RLS due to dopaminergic medications relates to a predisposition for impulse control behaviours and disorders. RLS (WED) patients have reported compulsive gambling, shopping and hypersexuality.94,95 More bizarre behaviours include dressing up in pretend play clothes for conventions (i.e., cosplay), not wearing seatbelts despite several citations and even prescribed medication hoarding.96 Curiously, one case report documented an older RLS (WED) patient (taking dopamine agonists to treat her RLS symptoms) who compulsively maintained a ‘secret stash at home’ by obtaining duplicate prescriptions in order to increase her medication dosage and frequency. This behaviour led to several QoL deficits for the patient: increased RLS (WED) symptom severity, extreme dizziness and frequent falls.96

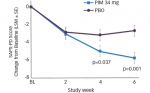

Finally, the rotigotine transdermal patch is the most recently (FDA) approved treatment for RLS (WED).97,98 Rotigotine is a transdermally applied non-ergolinic dopamine receptor agonist. As a transdermal patch, a steady-state dose delivery can be maintained that presumably results in the lower rates of augmentation for patients with moderateto- severe RLS (WED) symptoms.99 Rotigotine falls into a new class of non-oral treatment method for RLS (WED). In a 6-month double-blind trial performed in Europe, patients with moderate-to-severe RLS were randomised to fixed dosages of 1, 2 or 3 mg/day of the rotigotine transdermal patch or placebo. They found that RLS–QoL scores improved in a dose-dependent manner, and 31 % of patients achieved complete relief of RLS (WED) symptoms. However, many patients reported adverse events, most commonly: application site reaction, nausea, headache, vomiting and pruritus resulting in 52 out of 341 (15.2 %) patients withdrawing from the study, 24 of whom were part of the 3 mg group.100 This represents another example that may limit the improvements in QoL caused directly from pharmacological treatments.

Thus, while dopaminergic medications for RLS (WED) are beneficial for patients, healthcare providers should be aware of the side-effect profile and invariably its potential negative impact on QoL. As a result, providers should individualise their care with each patient and their family that includes well-rounded dialogue regarding the weighted cost and benefit of introducing the dopamine agonists as treatment option.

Opioids

Opioids may be used to treat more severe cases of RLS (WED),84,101,102 but may carry a stigma and thus may impact the willingness of RLS(WED) patients to use this class potentially affecting QoL. The mostrecent double-blind study has in fact shown the marked improvement in RLS symptoms with the introduction of opioid therapy even among patients with previously intractable symptoms. Interestingly, a longterm follow-up study for patients using opioids has shown a low risk of addiction, yet there are indeed some case reports of patients endorsing symptoms consistent with opioid dependence.103 In fact, opioid dependence has been linked to several QoL deficits, particularly in withdrawal when patients may suffer insomnia, depression and anxiety, among other symptoms.104 A more recent study conducted by Trenkwalder et al. investigated the prolonged release of oxycodonenaloxonein patients with severe RLS (WED) symptoms after failed treatment using first-line pharmacological methods. This doubleblind study was conducted over 12 weeks with a 40-week open-label extension phase. An average 16.6-point reduction on the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG) severity scale was observed – a transition from ‘severe’ symptoms to ‘mild’ or ‘moderate’. Authors reported that 73 % of patients in the double-blind phase and 57 % of patients in the extension phase experienced treatmentrelated adverse effects: 13.3 % and 10.6 % of patients withdrew due to adverse effects, respectively.105 In addition, worsening of sleep apnoea may occur with chronic opioid use.102 Worsening apnoea symptoms can affect patient’s QoL by increasing daytime sleepiness, decreasing energy and fatigue.106,107 Therefore, benefits gained by the use of opioids can potentially be negated by deficits associated with withdrawal and apnoea augmentation, but benefits are lost altogether in patients who refuse to use this class of medication.

Iron Therapy

While iron therapy has been shown to be beneficial for some patients with RLS,108 there are certainly some considerations related to QoL that may be of importance. Patients with low serum ferritin may experience secondary RLS (i.e., RLS symptoms are caused by iron deficiency), as well as higher periodic limb movements per hour during sleep than patients with high ferritin.108 A study conducted by Wang et al. has shown that, in RLS (WED) patients with low serum ferritin, oral iron intake improves International Restless Leg Scale (IRLS) scores in patients taking iron as treatment, but this finding was not statistically significant (p=0.07).109 In a study by Earley et al. patients were administered 1,000 mg intravenous (IV) iron dextran.107 Using the Johns Hopkins Restless Legs Symptom Severity Scale, it was determined that IV iron dextran improved global RLS symptom severity, and these improvements were seen 2 weeks later.107 Furthermore, 60 % of patients showed complete remission of RLS symptoms for 3–36 months following a single IV iron treatment. While one patient in this study was treated for anaphylaxis after iron infusion, no other adverse effects were reported.110 In general, adverse effects of iron therapy include abdominal pain, nausea or vomiting.111 Although RLS symptom severity may be reduced and directly improve patient QoL, adverse effects due to medication can indirectly cause QoL deficits that were not originally present. Generally, iron treatment can be beneficial and carries low risk; however, dosages should be carefully monitored to avoid adverse effects.

Benzodiazepines

Other less-common pharmacological treatments include benzodiazepines. The benzodiazepine clonazepam was investigated by Saletu et al. to determine treatment effectiveness. They found that clonazepam allowed patients relief from insomnia due to RLS symptoms and increased sleep efficiency, but patients had decreased sleep quality, frequent awakenings and reduced scores for well-being, attention and concentration.112 Another study, involving both clonazepam and temazepam, found that total leg movements of six patients with the RLS and periodic limb movements during sleep were not changed in both treatment groups.84,113 Thus, clonazepam may not be a preferred treatment method due to its uncertain efficacy and negative effects on patient sleep and cognition – factors central to patient QoL.

Anti-epileptic Medications

Gabapentin enacarbil, a prodrug of the gamma amino butyric acid (GABA) analogue gabapentin, received FDA approval in 2011 for treatment of moderate-to-severe RLS (WED) symptoms.114 Gabapentin enacarbil is preferred to other anti-epileptic medications due to its efficacy in absorption, longer duration of action and tolerability, which may also have a more positive effect on QoL for patients.47,115 A study by Happe et al. looked at QoL and sleep quality in patients receiving gabapentin for RLS (WED). They found a significant reduction in daytime sleepiness and significant increase in sleep quality, but depression, anxiety and QoL index (QLI) score improvements were not found to be significant.116 This can possibly be due to the fact that gabapentin enacarbil has been reported to cause decreased libido, depression and dizziness in RLS patients.117 In this case, QoL improvements may have been negated by medication-induced QoL deficits and, thus, clinicians should discuss with patients potential negative effects on mood before prescribing this treatment.

Botulinum Toxin

Another method, botulinum toxin, has been tested clinically with mixed results. One pilot trial by Agarwal et al. found statistically significant improvement in RLS symptom severity during the first 4 weeks of treatment. Variables often measured as part of QoL surveys – pain, disease severity and patient impression of severity – showed significant improvement, thus indicating that botulinum toxin could be a viable treatment option in improving QoL in RLS sufferers.118 However, a doubleblind,placebo-controlled study of botulinum toxin for RLS by Nahab et al. found no significant improvement in RLS symptoms or clinical global Improvement.119 Clearly, based on the mixed results from the limited number of studies, further investigation is needed to assess the role ofbotox as a RLS therapeutic.

Summary of Pharmacological Treatments and Quality of Life

Although further study is needed to determine the extent to which side effects introduce or exacerbate QoL deficits, or the extent to which these deficits outweigh improvements due to symptom alleviation, it is clear that the deficits associated with current pharmacological treatment are not only numerous but also serious. All current medications, including those that are FDA-approved and those that are not, come with side effects that may reduce the extent to which QoL is improved in RLS (WED) patients. Thus, not only is it imperative for providers to discuss side effects of the medications used to treat RLS (WED), but also to point out that the treatments themselves may have a negative impact on QoL. As a result, providers should strive to find a balance of successful treatment of RLS (WED) symptoms with the least negative (and potentially positive) impact on QoL.

Non-pharmacological Intervention and Strategies – Effects on Quality of Life

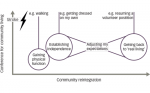

Many studies have been published in recent years emphasising behavioural strategies for the treatment of RLS (WED), in conjunction with or even as a substitute for pharmacological treatments. These strategies have the added advantage of treating patients largely without unwanted side effects. Behavioural intervention in the treatment of RLS (WED) is a relatively new approach, and methods include improving sleep hygiene, using compression devices, exercise and yoga and nearinfrared light treatments.

Reports have shown the importance of good sleep hygiene in maintaining good quality of sleep.120–122 There are a few sleep hygiene points that are particularly pertinent for RLS (WED) patients. This includes the avoidance of alcohol and stimulants, such as caffeine and nicotine, which can lead to exacerbation of RLS (WED) symptoms.122 Another important point of sleep hygiene includes maintaining a regular sleep– wake cycle. Cognitive-behavioural therapy has been shown to result in some improvement in sleep log measures of sleep–wake times in subjects with Periodic Limb Movement Disorder, a disorder related to RLS.123 Other sleep hygiene practices may or may not have any utility for patients with RLS (WED).124

Eliasson and Lettieri carried out a study on the use of sequential compression devices (SCDs) by RLS (WED) patients. Participants were asked to use this device that wrapped around the leg for an hour each evening before the usual onset of RLS (WED) symptoms. Patients completed questionnaires to assess RLS (WED) severity (RLS-QLI, 40-point scale), daytime sleepiness (Epworth, 24–point scale) and impact of RLS on QoL both before and after 1–3 months of SCD therapy. QoL measures used were social function, daily task function, sleep quality and emotional well-being. They found that severity score improved from 24/40 to 8/40 (p=0.001), Epworth Sleepiness Scale score improved from 12/24 to 8/24 (p=0.05) and QoL scores improved in all areas.14

While yoga can be grouped into the category of ‘exercise’, separate studies have been carried out showing the efficacy of both general exercise and yoga in managing RLS (WED). One study by Auckerman et al. enrolled 11 participants in aerobic and lower-body resistance training for 3 days per week. Using the IRLSSG severity scale, they determined that RLS (WED) symptoms decreased by 8 % in the control group, and by 39 % in the exercise group.125 Another study used the SF-36 to assess QoL changes due to physical activity in patients with diabetes with RLS (WED). More physically active RLS (WED) patients had increased scores in functional capacity and general health state, with decreased scores in physical limitation and pain. However, they found that symptom severity did not vary according to physical activity.126 A study published in 2011 by Innes and Selfe looked at the effect of yoga on older women with RLS (WED). They randomised 20 women into two groups: a yoga group and an educational film group. The yoga group engaged in active yoga sessions, whereas the film group watched an educational video and engaged in group discussions. Both groups met twice weekly for 8 weeks. The authors found that the yoga group showed significantly greater improvements than controls in sleep quality, greater reductions in prevalence of insomnia and greater increases in average sleep duration. Relative to controls, yoga group participants also showed significantly greater reductions in perceived stress, mood disturbance, state anxiety and both systolic and diastolic blood pressure.127

Preliminary research has been performed investigating the effectiveness of monochromatic near-infrared light energy in decreasing symptoms associated with RLS (WED). Mitchell et al. evaluated the effects of nearinfrared light applied to patients’ legs; the control group was subjected to the same device with no actual light administered. They found that over a period of 5 weeks the experimental group had decreased RLS (WED) symptom severity (using IRLS scale) by 12.7 (±7.7) compared with a decline of 4.4 (±3.6) within the control group. It was also found that the experimental group had decreased symptom severity 4 weeks post-treatment, whereas the control group did not.128 Because thisserved as one of the first studies to evaluate this therapy, overall efficacy remains to be determined with future studies, but nonetheless provides hope for alternative non-pharmacological options.

Unconventional Patient Self-treatment Strategies

Although RLS (WED) patients take prescription medications and perform recommended exercises and behavioural changes, many patients also pursue extreme, and sometimes bizarre strategies, to relieve their symptoms. Search engines such as Google and PubMed can help identify some common trends regarding unconventional strategies, new interventions and off-label uses of medication being practised by RLS patients. Examples of self-reports from patients encountered in the Johns Hopkins Sleep Centers are listed in Table 2 to illustrate the extentpatients may strive to achieve relief from their RLS symptoms. In general, these strategies include specific dietary options (vinegar, Gatorade®, peppermint tea, etc.), applying pressure or specific substances around the limbs (wearing rubber band around limb, Vick’s VapoRub®, urine on legs, etc.) and even sexual intercourse and masturbation. Due to the nature of these treatments, no QoL data have been published or reported but QoL inferences are made here for the purposes of this article. While many strategies used by patients for symptom relief are benign, others have the potential to cause severe life-threatening side effects.For example, quinine, although frequently prescribed off-label to treat leg cramps and RLS, has been associated with serious haematological reactions and side effects and is not routinely recommended as treatment by the experts in the field. Any factor that focuses attention on other activities, such as social activity, involvement in video games or participation in arts and crafts, have also been reported to decrease symptoms.129,130 Interestingly, daily involvement in these activities could potentially help increase patient QoL.

Lastly, marijuana use is often reported by RLS (WED) patients to decrease symptom severity, but no studies have been published testing the effectiveness of marijuana to improve RLS symptoms or affect QoL. There have been, however, previous studies and case reports documenting the efficacy of marijuana and tetrahydrocannibinol in treating muscle spasms.131,132 Because of this, medical marijuana may be prescribed to RLS patients in some states. According to the reports from patients who have used marijuana, it often takes only a small amount of the drug to relieve RLS symptoms, with complete symptom relief occurring within 2–3 minutes.133 This has the potential for great improvements in patient QoL, but in regions where marijuana use is illegal, negative QoL impact is a genuine possibility – this may occur through arrest, social repercussions from friends and family and, of course, potential systemic damage – particularly lung damage – if smoked regularly.

It is difficult to assess whether or not these unconventional strategies provide any real benefit to patients without formal scientific investigation.In certain cases, these treatments may be benign and in others they can be detrimental. However, it is clear that patients will go to great lengths to experience relief from RLS (WED) symptoms.

Summary

RLS (WED) is a chronic illness that can significantly affect the health, well-being and QoL in patients with moderate or severe disease. Due to the economic impact of management and treatment of this disease, it can have a high financial, personal and social burden to the patient, family and community.31 Currently, patient RLS QoL is primarily impacted by various pharmacological treatments, but these medications often come with numerous unwanted side effects that further affect patient QoL. Non-pharmacological and behavioural treatments have shown promising results, but further studies should be performed in this area to identify effective non-pharmacological strategies for RLS patients. Other options that need further investigation include the impact of RLS support groups on patients’ QoL. The establishment of support groups, such as the Willis–Ekbom Disease Foundation, allows patients to join social networks, share experiences and coping strategies and learn relevant information about RLS that may improve QoL.134 Further studies should be carried out to assess the effectiveness of RLS support groups in improving QoL.