Meningiomas comprise approximately 20% of adult primary intracranial neoplasms.1 Of these, benign meningiomas are known to have an indolent growth pattern, usually without infiltration into adjacent nervous tissue.2–5 Because meningiomas have a well-circumscribed character, surgery has historically been the preferred treatment when total resection can be achieved with reasonable morbidity. Surgical resection has resulted in five-, 10-, and 15-year progression-free rates of 93, 80, and 68%, respectively.6 Despite the development of multiple techniques designed to minimize morbidity while obtaining a surgical cure, however, complete resection remains difficult and is not achievable in approximately 20–30% of presenting patients because of multiple regional involvement, severe adherence to or invasion of the brainstem, involvement of cranial nerves, or encasement of the vertebrobasilar circulation.6–11 Currently, controversy exists as to whether skull base meningiomas, especially those involving the petroclivus and/or cavernous sinus, are best treated with radical resection, subtotal resection followed by radiosurgical treatment of the residual lesion, or radiosurgical treatment alone.

Petroclival Tumors and Cavernous Extension

Meningiomas of the petroclival region usually involve the petrous apex and the upper two-thirds of the clivus.10 Most are complex and, with modest enlargement, may involve multiple regions. Clival extension is usually unilateral for those tumors involving the upper and midclival regions.10 However, additional complexity exists for those centrally located lesions with respect to the clivus that have bilateral cavernous sinus involvement and/or extradural extension into the sphenoid sinus.10

Petroclival meningiomas are among the most difficult tumors of the cranial base for which to obtain surgical cure. Therefore, treatment must take into account the natural history of the tumor, degree of extension, neurovascular involvement, and the patient’s level of disability.12,13 Despite significant improvements10,14–17 in the surgical treatment of petroclival meningiomas, tumor may be left behind because of the invasion of the cavernous sinus, encroachment or encasement of cranial nerves, involvement of cerebral arteries, or invasion of the brainstem pial membrane. On this note, the management of tumors with neurovascular involvement has changed considerably over the past few years. Appropriately, cautious subtotal resection has become the preferred treatment to reduce post-operative morbidity, along with the addition of radiation treatment of tumor remnants.18–21

Meningiomas along the medial sphenoid wing that invade the cavernous sinus are also a treatment challenge because of the possibility of tumor infiltration of the traversing cranial nerves and internal carotid artery and, to a lesser degree, the involvement of the adjacent pituitary gland.22 The goal of surgical cure must therefore take into account local invasion of neurovascular structures within the cavernous sinus. As a consequence, several authors have emphasized the use of subtotal resection to limit the risk for permanent post-operative cranial nerve or the potential for vascular injury over complete resection.7,9,12,23 The long-term outcome after subtotal resection of meningiomas within the cavernous sinus alone is, however, associated with an unacceptably high symptomatic recurrence rate.24

Radiosurgical Treatment

Despite the high symptomatic recurrence rate and microsurgical improvements over the past few years, subtotal resection of meningiomas along the skull base, particularly those within the petroclival and cavernous sinus locations, remains a desired surgical outcome because such limited resection lends an acceptable level of morbidity.7,11,25-27 Because of the unacceptable morbidity of radical resection, along with the high incidence of recurrence, adjuvant techniques for treating these tumors have been developed.

Early studies from the 1980s demonstrated that external-beam field radiation therapy could provide durable local tumor control for those benign meningiomas treated with subtotal resection through improved progression-free survival rates.28–30 As more conformal therapies were developed, higher radiation doses could be administered while sparing dose to surrounding neural structures, resulting in an additional improvement in the 10-year progression-free survival rate. In a more recent study, Mendenhall et al.31 have shown five-, 10-, and 15-year local control rates of 95, 92, and 92%, respectively, for meningiomas treated with radiation therapy subsequent to subtotal resection.

With the addition of 3D treatment planning, improvements in conformality have come about through the use of stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) (single conformal treatment) and stereotactic radiotherapy (SRT) (fractionated conformal treatments).32 SRS is useful in the treatment of meningiomas at locations in which surgery may cause damage to neurovascular structures, especially those involving the petroclivus region and cavernous sinus.32 Fractionated SRT is more useful for those tumors that arise near critical structures such as the brainstem or optic chiasm.32 The use of highly focused single-fraction radiation to irregular tumor volumes, along with steep dose gradients in radiosurgery, significantly protects adjacent critical structures from delayed radiation-induced injury.

SRS has become a popular alternative or adjuvant to resection in order to reduce the risk for tumor recurrence of skull base meningiomas.25,33–35 The efficacy of this method is clearly demonstrated by radiosurgical control rates, which have been reported to be extremely high: approaching or exceeding 90% in many contemporary studies involving either linear accelerator-based systems or gamma knife surgery (GKS).2,3,25,31,36–41 The efficacy of stereotatic radiosurgery as an alternative to aggressive resection was confirmed in a recent study published by Davidson et al.42 They found that for those patients treated with GKS with an initial subtotal resection or with recurrent disease, the five- and 10-year actuarial progression-free survival rate was 100 and 94%, respectively.42 They state that the progression-free survival rate might have been 100% had a single patient had her tumor growth area more adequately covered by the treatment plan.

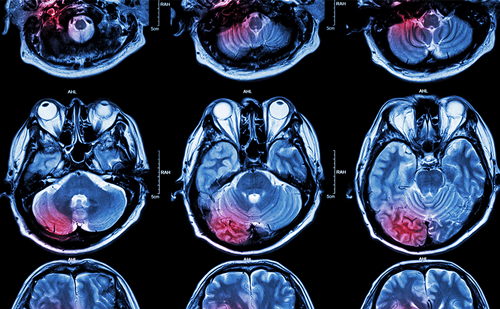

Many have also considered radiosurgery to be an excellent stand-alone treatment of skull base meningiomas of less than 3cm. The caveat of such notable outcomes appears to be associated with the histological subtypes of the tumors. Stafford et al. 5 found that the five-year local control rate of meningiomas treated radiosurgically either primarily or subsequent to surgical treatment was 93, 68, and 0% in patients with benign, atypical, and malignant subtypes, respectively. Furthermore, the five-year cause-specific survival rate in patients with benign meningiomas was 100% compared with 83% in patients with atypical meningiomas and 0% in patients with a malignant meningioma after radiosurgery. Despite reports documenting outstanding radiosurgical growth control rates (as an alternative to or part of a staged therapy with microsurgery), radiosurgical treatment fails in some cases, and little is known about the natural history of tumors that fail to stabilize after radiosurgery. There is very scant literature on the growth patterns of such tumors.43 Couldwell et al.43 have reported that aggressive regrowth of meningiomas can follow failed radiosurgery, even in a substantially delayed fashion (see Figure 1). In several patients, meningiomas recurred several years after radiosurgical treatment (up to 14 years), indicating that consistent and extended follow-up evaluations should be performed in all cases of meningiomas, even benign meningiomas, after radiosurgery. Given this late regrowth potential, there is the distinct possibility of an increasing rate of treatment failure over time after radiosurgery.43 In this analysis of failed radiosurgically treated meningiomas, tumor regrowth occurred both within and beyond the field of treatment.43

Conclusion

Gross total resection remains the preferred treatment for benign meningiomas that can be resected with reasonable morbidity and for patients requiring immediate decompression for symptomatic relief. However, preliminary (10-year) results of radiosurgical treatment of small meningioma remnants or small inoperable tumors have influenced the management of these tumors. Radiation therapy has gained wide acceptance in the treatment of incompletely resected meningiomas, as well as a primary treatment option for inoperable tumors. Furthermore, SRS is a convenient single-day alternative to surgery for meningiomas located along the skull base, particularly those along the petroclival region or within the cavernous sinus, where attempted resection may place critical neurovascular structures at risk.

Although there are reports of long-term progression-free survival, radiation treatment of meningiomas fails in some cases. With the increasing number of patients undergoing SRS for benign tumors, careful attention is warranted, as some lesions will progress despite ‘adequate’ treatment. Therefore, extended (exceeding 10 years) follow-up deserves consideration in all patients after radiosurgery. ■

Acknowledgments

We thank Kristin Kraus, MSc, for editorial assistance in preparing this paper.