Cervical anterior discectomy (CAD) was introduced by Smith and Robinson, and Cloward, in 1958.1,2 They described the anterior approach to the cervical disc. After removal of the disc and herniated part an autograft taken from the iliac crest was introduced in the intervertebral space to promote fusion between the two adjacent vertebral bodies. The introduction of a microscope facilitated the procedure enormously. At this time the main reason for performing a CAD is still degeneration of the disc with signs and symptoms due to compression of the nerve root and/or spinal cord by a herniated disc or spondolytic spurs.

Nowadays, various kinds of CAD are distinguished depending upon the implant that is used to fill the intervertebral space. A discectomy can be performed solely without introducing any implant in the intervertebral space (CAD). If an implant is used with the intent of fusing the adjacent vertebral bodies it is called in literature a cervical anterior discetomy with fusion (CADF). Recently, prostheses have been used in order to maintain mobility at the operated segment.

A standard abbreviation has not been used yet, but for this review we will use CADP. The advantages and disadvantages of each of the procedures will be addressed below.

CAD was described by Hirsch in 1960.3 Through an anterior approach the cervical disc was removed as were the compressing factors on the nerve root or spinal cord, such as herniated disc or accompanying spondylotic spurs. Since the intervertebral space will collapse after removal of the disc an adequate decompression of the

exiting nerve roots should be achieved.

In the case of CADF an implant is used. Various implants can be used, ranging from autograft – most frequently obtained from the iliac crest – allograft, cages filled with bone (auto- or allograft) or biomaterials, or polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) bone cement. PMMA is used as a spacer without the intention of promoting fusion, but eventually fusion occurs around the PMMA. After performing a thorough discectomy the implant is introduced. The disc space is slightly overdistracted. This manoeuvre will increase the height of the neuroforamina.4,5

The use of a plate as an adjunct to CADF is still subject of discussion. It has been proven that for one- or two-level CADF, a plate does not have any advantage and is considered not to be useful.6–8 Recently, arthroplasty has been introduced. The theoretical advantages of CADP are, in the first instance, providing at least as good clinical results as CADF. Furthermore, prostheses maintain mobility and could prevent the occurrence of degeneration of the adjacent segment (adjacent disc degeneration [ADD]). There is no benefit relating to the clinical result.9

The existence of ADD is subject to debate. The proponents of arthroplasty frequently cite the article by Hilibrand,10 in which he reported an annual rate of ADD after fusion of 2.9 % after 10 years of follow-up. However, correction for the patients lost to follow-up and pre-existing degeneration of the adjacent segment decreased the annual rate to 0.4 %.11 Furthermore, recent studies in asymptomatic volunteers disclosed that degeneration of initially normal discs and progression of existing degeneration is a natural phenomenon.12–14

Therefore, it can be questioned whether ADD is really induced by fusion of a segment or is a natural phenomenon. Finally, it is remarkable that ADD was not a subject in many of the recently published results of randomised clinical trials (RCTs) comparing arthroplasty with CADF.15

From the available studies a benefit for athroplasty in relation to the prevention of ADD has not been proven.15 The results for each procedure relating to relief of arm and/or neck pain are within the same range. Over 75 % of patients have a good-to-excellent result regarding arm pain; the results for concomitant neck pain are slightly worse.6,16 For one- or two-level degenerative disc disease a difference in clinical outcome has not been established comparing CAD or CADF.6 Any clinical benefit of the use of a prosthesis compared with CADF has also not been proven.9

The major theoretical advantage of CADF is maintenance of the disc height and lordotic shape of the cervical spine. However, a correlation with a clinical effect has never been established.17

The most common complications of CAD are hoarseness and dysphagia. A lesion of the recurrent laryngeal nerve can lead to dysfunction. Since the approach to the disc and the discectomy is the same for all kinds of CAD, they are referred to as approach-related complications; in most instances they are asymptomatic. Of the direct post-operative symptomatic patients, a large number become asymptomatic after several months.

In different studies the prevalence of persistent hoarseness varied between 0 % and 5.0 %.18–20 The prevalence of dysphagia varied from 50 % within one month post-operatively to 21 % after one year.21–24 Other (rare) approach-related complications are Horner’s syndrome, lesion of the dura, worsening of neurologic symptoms, perforation of the oesophagus, lesion of the vertebral artery, infection of the wound and post-operative haemorrhage.18

Complications related to implants also occur. The most frequent complication of an autograft taken from the iliac crest is pain at the donor site. Usually this pain diminishes, but can remain persistent.25,26 This complication and others related to obtaining a bone graft, like neurovascular lesions, can be prevented by using cages. However, as well as subsidence, pseudoarthrosis can occur.

The main question remains as to whether this is clinically significant. In observational studies, these were not correlated to clinical failure.27–30

A specific complication related to cervical disc prostheses is periprosthetic ossification.31–36 Bone is formed around the prosthesis and can restrict movement. It is remarkable that this occurrence does not alter clinical outcome. More recently, problems due to design have been reported. Metal-on-metal total disc prostheses induced a lymphocytic reaction with signs and symptoms after initial clinical success. They underwent surgery again with removal of the system and fusion. Although three of the four reported cases had lumbar disc prosthesis, surgeons should be aware of possible failure in the future due to the design of the prosthesis.

In conclusion, CAD is a safe procedure with a good-to-excellent result in most cases. The debate whether to fuse or not and, if fusion is the goal, which implant should be applied is still not closed. Before developing fancy new implants, a definitive answer to the question of CAD with or without fusion should be provided. A large RCT on this subject with the participation of several centres in Europe would probably solve this question. The available literature is at this time certainly not in favour of cervical arthroplasty. I doubt whether based on recent investigations this will change, since a thorough review by independent epidemiologists will certainly reveal many biases and flaws.

Anterior Cervical Discectomy – An Overview of Technique and Developments for the Future

Abstract

Overview

Cervical anterior discectomy was introduced in the late 1950s. The main indication was radicular symptoms due to cervical degenerative disc disease. The results for this straightforward procedure are in most instances excellent. An overview is given of current anterior surgical possibilities including the necessity of implants. Attention is also given to possible future developments.

Keywords

Surgery, anterior cervical discectomy, degeneration, intervertebral disc, outcome

Article

References

- Smith GW, Robinson RA, The treatment of certain cervical spine disorders by anterior removal of the intervertebral disc and interbody fusion, J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1958;40:607–23.

- Cloward RB, The anterior approach for removal of ruptured cervical disks, J Neurosurg, 1958;15:602–17.

- Hirsch,C, Cervical disc rupture: diagnosis and therapy, Acta Orthop Scand, 1960;30:172–86.

- Bartels, RH, Donk, R, van-Azn, RD, Height of cervical foramina after anterior discectomy and implantation of a carbon fiber cage, J Neurosurg, 2001;95:40–2.

- Sekerci Z, Ugur A, Ergun R, et al., Early changes in the cervical foraminal area after anterior interbody fusion with polyetheretherketone (PEEK) cage containing synthetic bone particulate: a prospective study of 20 cases, Neurol Res, 2006;28:568–71.

- Jacobs W, Willems PC, van Limbeek J, et al., Single or double-level anterior interbody fusion techniques for cervical degenerative disc disease, Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2011;19;1:CD004958.

- Matz PG, Ryken TC, Groff MW, et al., Techniques for anterior cervical decompression for radiculopathy, J Neurosurg Spine, 2009;11:183–97.

- Resnick DK, Trost GR, Use of ventral plates for cervical arthrodesis, Neurosurgery, 2007;60:S112–7.

- Bartels RH, Donk R, Verbeek AL, No justification for cervical disk prostheses in clinical practice: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, Neurosurgery, 2010;66:1153–60.

- Hilibrand AS, Carlson GD, Palumbo MA, et al., Radiculopathy and myelopathy at segments adjacent to the site of a previous anterior cervical arthrodesis, J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1999;81:519–28.

- Bartels RHMA, Evidence Based Medicine: A marketing tool in spinal surgery, Neurosurgery, 2009;E1206.

- Okada E, Matsumoto M, Ichihara D, et al., Aging of the cervical spine in healthy volunteers: a 10-year longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study, Spine, 2009;34:706–12.

- Okada E, Matsumoto M, Fujiwara H, et al., Disc degeneration of cervical spine on MRI in patients with lumbar disc herniation: comparison study with asymptomatic volunteers, Eur Spine J, 2011;20:585–91.

- Gore DR, Roentgenographic findings in the cervical spine in asymptomatic persons: a ten-year follow-up, Spine, 2001;26:2463–6.

- Botelho RV, Moraes OJ, Fernandes GA, et al., A systematic review of randomized trials on the effect of cervical disc arthroplasty on reducing adjacent-level degeneration, Neurosurg Focus, 2010;28:E5.

- Miller LE ,Block JE, Safety and effectiveness of bone allografts in anterior cervical discectomy and fusion surgery, Spine, 2011. [Epub ahead of print].

- Konduru S, Findlay G, Anterior cervical discectomy: to graft or not to graft? Br J Neurosurg, 2009;23:99–103.

- Fountas KN, Kapsalaki EZ, Nikolakakos LG, et al., Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion associated complications, Spine, 2007;32:2310–7.

- Kilburg C, Sullivan HG, Mathiason MA, Effect of approach side during anterior cervical discectomy and fusion on the incidence of recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, J Neurosurg Spine, 2006;4:273–7.

- Morpeth JF, Williams MF, Vocal fold paralysis after anterior cervical diskectomy and fusion, Laryngoscope, 2000;110:43–6.

- Bazaz R, Lee MJ, Yoo JU, Incidence of dysphagia after anterior cervical spine surgery: a prospective study, Spine, 2002;27:2453–8.

- McAfee PC, Cappuccino A, Cunningham BW, et al., Lower incidence of dysphagia with cervical arthroplasty compared with ACDF in a prospective randomized clinical trial, J Spinal Disord Tech, 2010;23:1–8.

- Mendoza-Lattes S, Clifford K, Bartelt R, et al., Dysphagia following anterior cervical arthrodesis is associated with continuous, strong retraction of the esophagus, J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2008;90:256–63.

- Riley LH III, Vaccaro AR, Dettori JR, et al., Postoperative dysphagia in anterior cervical spine surgery, Spine, 2010;35:S76–85.

- Bartels RHMA, Single-blinded prospective randomized study comparing open versus needle technique for obtaining autologous cancellous bone from the iliac crest, Eur Spine J, 2005;14:649–53.

- Ryken TC, Heary RF, Matz PG, et al., Techniques for cervical interbody grafting, J Neurosurg Spine, 2009;11:203–20.

- Bartels RH, Donk RD, Feuth T, Subsidence of stand-alone cervical carbon fiber cages, Neurosurgery, 2006;58:502–8.

- Bartels RH, Beems T, Schutte PJ, et al., The rationale of postoperative radiographs after cervical anterior discectomy with stand-alone cage for radicular pain, J Neurosurg Spine, 2010;12:275–9.

- Moon HJ, Kim JH, Kim JH, et al., The effects of anterior cervical discectomy and fusion with stand-alone cages at two contiguous levels on cervical alignment and outcomes, Acta Neurochir (Wien), 2011;153:559–65.

- Pechlivanis I, Thuring T, Brenke C, et al., Non-fusion rates in anterior cervical discectomy and implantation of empty polyetheretherketone cages, Spine, 2011;36:15–20.

- Beaurain J, Bernard P, Dufour T, et al., Intermediate clinical and radiological results of cervical TDR (Mobi-C) with up to 2 years of follow-up, Eur Spine J, 2009;18:841–50.

- Lee JH, Jung TG, Kim HS, et al., Analysis of the incidence and clinical effect of the heterotopic ossification in a single-level cervical artificial disc replacement, Spine J, 2010;10:676–82.

- Quan GM, Vital JM, Hansen S, et al., Eight-year clinical and radiological follow-up of the bryan cervical disc arthroplasty, Spine, 2011;36:639–46.

- Suchomel P, Jurak L, Benes V III, et al., Clinical results and development of heterotopic ossification in total cervical disc replacement during a 4-year follow-up, Eur Spine J, 2010;19:307–15.

- Yi S, Kim KN, Yang MS, et al., Difference in occurrence of heterotopic ossification according to prosthesis type in the cervical artificial disc replacement, Spine, 2010;35:1556–61.

- Ryu KS, Park CK, Jun SC, et al., Radiological changes of the operated and adjacent segments following cervical arthroplasty after a minimum 24-month follow-up:

comparison between the Bryan and Prodisc-C devices, J Neurosurg Spine, 2010;13:299–307.

Article Information

Disclosure

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Correspondence

Ronald HMA Bartels, Department of Neurosurgery, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre, R. Postlaan 4, 6500 HB Nijmegen, The Netherlands.HMA Bartels, Department of Neurosurgery, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre, R. Postlaan 4, 6500 HB Nijmegen, The Netherlands. E: r.bartels@nch.umcn.nl

Received

2011-04-30T00:00:00

Further Resources

Trending Topic

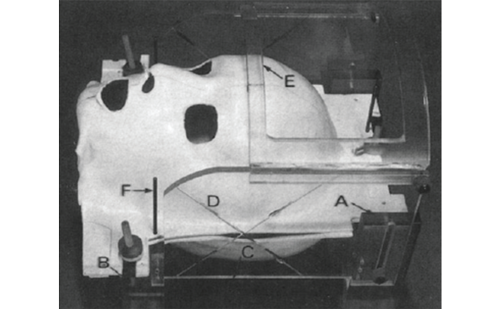

Intracranial radiosurgery, no matter the means or methods of administration, is predicated on a core set of principles, including head immobilization and precise delineation of the treatment target. For some five decades after Leksell introduced the concept of stereotactic radiosurgery in 1951,1 rigid head fixation via an invasive device was an integral component towards these ends. […]

Related Content in Neurosurgery

Studying cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is essential for diagnosing many central nervous system (CNS) diseases, including infection, inflammation and malignancy. Lumbar puncture is a relatively safe and routinely performed procedure for extracting CSF.1 In this review, we summarize the essential CSF ...

Infections and their prevention have long been a significant concern for surgeons around the world. Surgical site infections (SSIs) represent a considerable burden for both patients and providers alike, as they often result in significant morbidity and mortality, as well ...

Cerebral cavernous malformations are commonly found in deep regions of the brain, such as the thalamus and brainstem.1 While posing a significant risk of hemorrage,2 they also present a surgical challenge as the rates of morbidity and mortality are high.1,3 ...

Recently released guidelines on the use of disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) include guidance on starting, switching, and stopping treatment. The guidelines, which were produced by a multidisciplinary panel and endorsed by the Multiple Sclerosis Association ...

The importance of recognizing and including cognition as a key factor to consider when ensuring comprehensive care for individuals with multiple sclerosis (MS) cannot be over emphasized. Unfortunately, despite it being accepted as a common symptom, cognitive function in MS ...

There has been an explosion of data in the field of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), not only from clinical studies but also studies that generate hypotheses and opportunities that may accelerate drug development. In order to make optimal use ...

This year, the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC) took place in Chicago, IL, US, July 22–26, 2018. During this major annual international meeting dedicated to the advancement of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and dementia science, an impressive array of the ...

Dural arteriovenous fistulas (dAVF)s are unique to the neuraxis as the arteriovenous shunt site is contained within the dural leaflets. They may be discovered incidentally or in a workup of a variety of potential neurological sequelae, including pulsatile tinnitus, ...

Brain arteriovenous malformations (bAVMs) are rare congenital lesions that confer a lifelong risk for hemorrhage. Treatment options for these lesions include microsurgical resection, embolization, and radiosurgery, alone or in combination. The goal of bAVM intervention is to eliminate the risk ...

Surgery for Occlusive Atherosclerotic DiseaseExtracranial-intracranial (EC-IC) bypass for revascularisation in the setting of atherosclerotic occlusive disease has remained a topic of intense interest and scrutiny over the last four decades. The underlying premise of EC-IC bypass in this setting is ...

What is Trigeminal Neuralgia? Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is a vexing clinical problem for a number of reasons, not least of which is clearly defining its clinical spectrum. A commonly accepted definition of TN is that of a facial pain syndrome ...

Neuromodulation Devices Vagus Nerve Stimulation Neuromodulation Devices Vagus Nerve Stimulation Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), first used for seizure treatment in the 1880s, was approved by the FDA in 1997 after decades of animal studies demonstrating reduction of chemically-induced seizures,1,2 and subsequent ...

Latest articles videos and clinical updates - straight to your inbox

Log into your Touch Account

Earn and track your CME credits on the go, save articles for later, and follow the latest congress coverage.

Register now for FREE Access

Register for free to hear about the latest expert-led education, peer-reviewed articles, conference highlights, and innovative CME activities.

Sign up with an Email

Or use a Social Account.

This Functionality is for

Members Only

Explore the latest in medical education and stay current in your field. Create a free account to track your learning.