The pressures of competition and multimillion dollar malpractice lawsuits have driven modern medical centers to invest heavily in technology. This in turn has driven the price of medical procedures to almost unacceptable levels. The hope is that applied technology can decrease the costs of each patient treatment. Image-guided surgery is an area that may lead to substantial savings in medical dollars. The scope of the approaches and the realistic surgical undertaking may lead to shorter hospital stays due to fewer complications related to extensive surgeries, less need for long convalescent and rehabilitation periods, and, consequently, a faster return of the patient to the workforce.

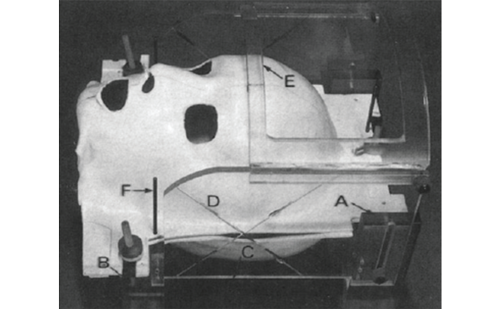

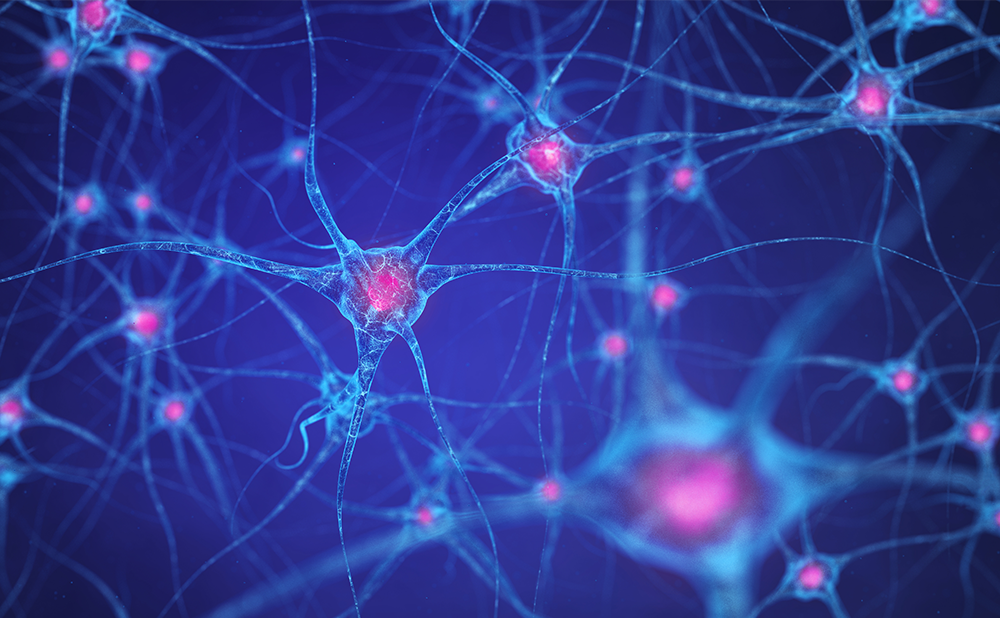

Information obtained during implant of a deep brain stimulator to control Parkinson’s disease symptoms. Upper left is a three-dimension reconstruction. White arrow shows the pyramidal tract relationship with the subthalamic nucleus. Red straight oblique line represents the electrode.

Ultimately, this results in decreasing the overall price of medical care. This concept has been exemplified in general surgery by endoscopic gall bladder resections and in neurosurgery by difficult skull base disease. These difficult tumors are now treated with transnasal procedures for skull base tumor resections1 followed by radiosurgery, reducing patient recovery, decreasing morbidity, and offering the patient complete control of his or her disease.2

Throughout the 20th century—mostly in its last quarter—remarkable noninvasive imaging techniques were developed primarily for diagnostic studies. Fast computers and smart software packages permitted the introduction of these images to the operating field in order to guide the surgeon. Digital fluoroscopy, ultrasound, computer tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and positron emission tomography (PET) are now brought to the operating room and combined with merging data set techniques, allowing the surgeon to take advantage of a wealth of information that was previously unavailable. The surgeons of the past relied upon the principle of exposure, exposure, exposure, and their individual knowledge of gross anatomy to perform surgery; the surgeons of the present rely on their knowledge of gross anatomy, anatomical imaging, and functional anatomy to perform minimally invasive procedures and solve previously unapproachable problems.

We are on the verge of perfecting realtime imaging in surgery. During the past decade the information brought during surgery by plain X-rays, fluoroscopy, and ultrasound was maximized and their limitations were established. Surgeons have now turned their eyes to the wealth of possibilities offered by portable CT scans and operating rooms equipped with interventional MRI scanners. MRI offers the possibility of not only exquisite anatomical information during surgery, but also the dynamic changes of this anatomy associated with realtime changes in function. It also carries the advantage of not being harmful to medical personnel, in contrast to techniques dependent on isotopes or X-rays. The operating room with MRI, also known as operating room of the future, is a focus of studies in major medical centers. The logistics and advantages of bringing a complex technology such as MRI to the operating room, or bringing the operating room to the complex MRI environment,3 has become a subject of symposia on modern surgery.4

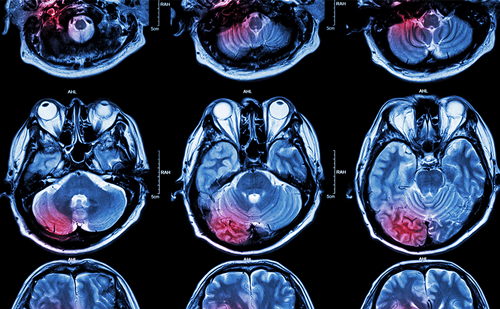

The evolving field of functional MRI has allowed the possibility of deciding before surgery the location of a fine function in the brain in relation to the pathology (see Figure 2). It has also allowed relating the complex wiring of the brain to the location of ‘brain pace makers’ (see Figure 1). All this information is readily related to imaging during surgery, as it was conducted on the cases presented in Figures 1 and 2. It is starting to appear in the market products that integrate information from multiple imaging sources with diffusion of fluids through tissues, such as brain parenchyma for delivery of drugs after resection. This is all achieved with mathematical precision.

Information obtained at the time of resection.

Similar information is being generated with the extent of therapeutic thermal application, electrical current, and radiation. Lasers or radiofrequency ablation, electrical stimulation with smart pacemakers capable of receiving and analyzing physiological clues, and radiation delivery with modulating capabilities are all novel approaches being developed.5,6

The operating room of the future for ‘guided surgery’ requires the realtime anatomical imaging technology to be related to function of the tissue under therapy at the moment of resection or modulation. This allows maximization of resection, drug infusion, and electrical tissue influence, and also taking advantage of radiation strategies to manipulate biological systems. The patient should be minimally invaded and maximally helped with the least expense to the society,7 this is the goal of ‘guided surgery’.