Epilepsy is one of the most common serious neurological conditions, has no geographic, social or racial boundaries and can affect people of all ages.1 It is frequently associated with co-morbidities, not just seizures, and is a condition that is linked with a high rate of premature death compared with that in the general population.1 The consensus proposal by the ad hoc Task Force of the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) Commission on Therapeutic Strategies defined drugresistant epilepsy (DRE) as the failure of two appropriately chosen and tolerated anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) (whether as monotherapy or in combination) to control seizures when used for an adequate period of time.2,3 The ideal goal for treating newly diagnosed epilepsy is to eliminate seizures while having minimal side-effects; however, in DRE, the treatment goals are required to be more modest.2,4,5 These involve: optimizing long-term seizure control, maximising quality of life (QoL), minimising side effects, maximising adherence and decreasing seizure severity and the postictal period.

The consequences of DRE have significant QoL implications for patients. These include: depression and anxiety;5–7 raised risk of mortality and morbidity;6,8–10 increased healthcare utilisation;4,11,14 more adverse events (AEs) with long-term use of AEDs;5–7,13 cognitive and memory impairment;6,7,14 seizure-related injuries;6,7 and impaired ability to obtain educational and work goals; to drive; establish families; and develop and maintain social relations.7,13 Out of a population in Europe of 850 million people, a conservative estimate of people with active epilepsy is 6 million (prevalence of 8.2/1000).15 Of these 6 million people, epilepsy is well controlled with AEDs in 70 %.15 In the remaining 30 % with DRE, onequarter to one-third (450 000–600 000 people) are potential candidates for epilepsy surgery.15 Two-thirds to three-quarters of the people with DRE (approximately 1.4 million) are candidates for other therapies such as vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) Therapy, ketogenic diet, deep brain stimulation (DBS) or experimental AEDs. According to a recent survey of epilepsy clinicians who were asked about the DRE treatment gap, around 40 % of DRE patients have undergone a comprehensive evaluation and, of this 40 %, the proportion who had not received VNS Therapy or epilepsy surgery was 83 %.16

Risks Beyond Seizures

In addition to the risks associated with seizures (e.g. falls), there are risks linked with the underlying disease, neurobiological dysfunction, social stigma and AEs. These create a complex picture, for example, the risk of depression may be heightened by other risk factors such as AED-associated side effects and social stigma.17,18 Estimates for the prevalence of adults with depression in epilepsy range from 20 to 55 %.17,19–23 Furthermore, depression can increase the risk of drug resistance, surgical failure and treatment-related AEs.18,24 There may even be common neurobiological–pathogenic mechanisms between the two conditions so that epilepsy may promote depression and vice versa.25–27 Mood disorders are a possible side effect of AEDs28 and these are the main determinants of QoL in people with epilepsy.29

Memory decline and dysfunction also represent major concerns in patients with DRE. In a longitudinal study of 249 patients with temporal lobe epilepsy followed for 2–10 years, significant progressive memory decline occurred in 53 % of 102 of medically treated patients, in 60 % of 147 of surgically treated patients (primarily left hemisphere surgery). Memory decline was accelerated by unsuccessful surgery.30 Memory deficits can also be aggravated by a number of AEDs31 and, withdrawal of AEDs following epilepsy surgery has been shown to lead to improved intelligence quotient scores in children.32

Seizure-related injuries can be severe and even lethal. In a Canadian population-based study, patients with epilepsy appeared to have more domestic-related injuries, although sports-related injuries occurred in these patients less often for the unfortunate reason of them having fewer opportunities to participate in sport, which again impacts on their health.33 The biggest difference in comparison with the general population can be seen in terms of premature death with a four to eightfold higher risk of premature death.34,35

One of the reasons for the greater risk of premature death in people with epilepsy is the raised risk of suicide in those patients with comorbid psychiatric disease. This corresponds to an adjusted rate ratio (95 % confidence interval [CI]) of 9.86 (8.11–12.0; p<0.0001) in men and 23.6 (18.6–30.1; p<0.0001) in

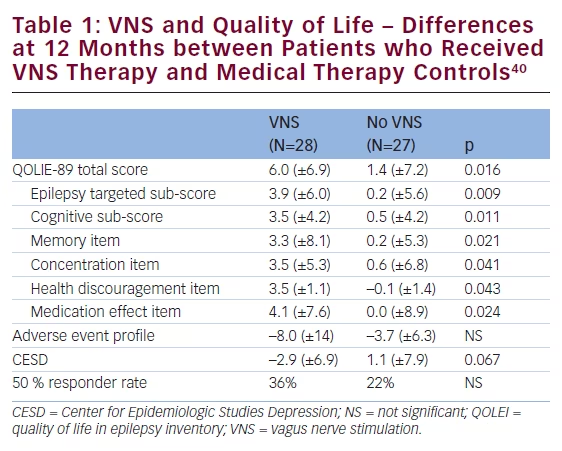

women.36 Sudden unexplained death in epilepsy (SUDEP) is another main reason for premature death in people with epilepsy and is the second principal neurological cause in terms of years of potential life lost.37 The incidence of SUDEP in patients with epilepsy is approximately 1.16 per 1,000 (0.95–1.36).37 There appears, however, to be as much as 100-fold variation in the incidence of SUDEP between the various patients groups. SUDEP occurred with the highest incidence in studies of candidates for epilepsy surgery and epilepsy referral centres (2.2:1000–10:1000) and with the lowest incidence in children (0–0.2:1000).38 In a study of long-term mortality in childhood-onset epilepsy, 245 children (median age 3 years) were followed up for 40 years, nearly half of the subjects (51/107) who were not in 5-year terminal remission died (i.e., ≥5 years seizure-free at the time of death or last follow-up).39 Of the total 60 deaths, 33 (55 %) were related to epilepsy, including SUDEP in 18 subjects (30 %). New data including 34,000 patients aged 10–54 years (232,000 years of follow-up) indicate that VNS therapy is associated with a rate reduction in SUDEP. VNS therapy has also been associated with a significant improvement in QoL (see Table 1).40

Defining Treatment Success in Difficult-to-manage Epilepsy

Successful epilepsy surgery has been defined by several different endpoints in the literature.41–43 These include 1-, 2-, 5- and 10-year seizure freedom rates, withdrawal of all AEDs, acceptable side effects, return to education or work, improved QoL or mood and decreased healthcare utilisation. When a patient is not an epilepsy surgery candidate, suggested definitions of successful ongoing treatment might

include: fewer seizures (especially dangerous seizures), decreased rescue therapy use, good tolerability of treatment (long-term retention), QoL/mood improvements, lack of drug interactions, ease of use and good adherence to treatment. Concerns with the older medications include: prominent drug interactions (phenobarbital, phenytoin and carbamazepine); poor oral absorption in children (phenytoin and carbamazepine); long-term side effects such as an undesirable serum lipid profile (phenobarbital, phenytoin and carbamazepine); negative effects on bone heath (phenobarbital, phenytoin, carbamazepine and valproate) and teratogenic effects (phenobarbital, phenytoin, carbamazepine, valproate and topiramate).

Patient-rated tolerability is a major determinant of QoL.44 Tolerability as assessed by long-term retention rates for several AEDs and VNS therapy, are shown in Figure 1. VNS therapy has a long-standing association with enhanced QoL.40 Good adherence to treatment is equally critical and leads to a number of beneficial outcomes, such as improved seizure control,45–48 enhanced QoL,46 lower rate of seizurerelated job loss,46 hospitalisation and emergency department visits,4,45,49 lower fracture and motor vehicle accident rates45,46 and lower mortality rate in adults.45 VNS therapy has also been associated with reduced healthcare utilisation and costs (see Table 2).50,51

Mood is another factor in defining treatment success. Depression is a common co-morbidity in epilepsy52 and depressed mood is a predictor of poor subjective sleep quality and increased daytime sleepiness.53 Further, depressed mood and anxiety are correlated with increased rates of AED-associated AEs54,55 and these symptoms are also significant predictors of QoL.44

In summary, managing epilepsy well is about more than controlling seizures and this needs to be recognised in planning and delivering services.56 When seizure freedom cannot be achieved, addressing depressive comorbidity and reducing the burden of AED toxicity is likely to be far more beneficial than interventions aimed at reducing the frequency of seizure alone.57

Closing the Treatment Gap in Drug-resistant Epilepsy – A Japanese Success Story

There are multiple possible causes that underlie the treatment gap in DRE. Economic reason is only one of them.58 Some involve the natural history of the disease, for example, the asymptomatic phase of illness or the person’s own explanatory model or treatment-seeking behaviour (e.g. self-neglect). There may also be deficiencies in health service provision; social stigma, which discourages treatment seeking; and other causes that are, at present, unknown due to lack of research.

The treatment gap for DRE should be reduced by identifying the underlying causes and addressing each for each society. In Japan, for example, one of the major causes behind the treatment gap was under-recognition of the significance of palliative therapy for DRE and a specific medical system, in which approval and indication for a novel treatment was strictly controlled by the government, making VNS an so-called ‘orphan device’ in early 2000s. After epileptologists carried out extensive lectures and seminar series, aimed at not only physicians but general citizens and government audiences, which emphasised the significance of palliative treatment. VNS was approved in 2010 and uptake since has been rapid. Responder data from the VNS Japanese all-patient registry are promising. In 385 patients with mean age 24 (±14.8 years), which included 55 % with prior epilepsy surgery, the rates of responders with >50 % seizure reduction were 39.1 % (n=358), 46.6 % (n=356), 56.0 % (n=350) and 58.6 % (n=321) after 3, 6, 12 and 24 months of VNS, respectively. There were no severe complications, and most common AEs were cough (9.1 %) and voice change (9.6 %).

It is estimated that <1 % of Japanese patients with DRE receive VNS therapy. The treatment gap for DRE must be reduced by identifying the underlying causes and properly acting to address each cause. There is a large treatment gap in Asian countries that is disproportionately large considering its rapidly growing economy.

Drug-Resistant Epilepsy – Overview of Neuromodulation Treatment Options

Neurostimulation targets and modalities may be intracranial and extracranial; the former includes closed loop DBS and cortical stimulation or closed loop responsive neurostimulator system (RNS).59

Anterior nucleus thalamus-DBS has been investigated in the SANTE trial.60,61 One hundred and ten patients with medically refractory partial seizures from 17 US centres were randomised. A reduced seizure frequency with DBS treatment was observed compared with the control group, which was reduced further over time: 56 % at 2 years and 69 % at 5 years. Thirty-four per cent of patients experienced side effects of some sort. In another randomised controlled trial of responsive intracranial stimulation using cortical or intracranial electroencephalography (EEG) as a readout (n=240) in which one-third of the patients had undergone prior epilepsy surgery or VNS therapy, a 37 % seizure reduction was reported for those who had undergone DBS versus 17 % in controls.62,63 Also in this trial, seizure outcome improved after longer follow up (up to 6 years). No negative effects were noted in mood or cognition.

In a pilot study of 10 patients with epilepsy who received non-invasive VNS via auricular branch VNS three times a day for nine months, five out of the seven patients who completed the study experienced significant seizure reduction.64 The therapy was safe and well tolerated.

There is limited experimental evidence for non-invasive VNS, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) and trigeminal nerve stimulation (TNS).

There is preliminary evidence that trigeminal nerve stimulation, which is available via dermal application with a subcutaneous option, may be safe and effective in reducing seizures in patients with DRE.65,66 However, further investigation is needed before trigeminal nerve stimulation can be considered a recommendable approach.

A randomised, double-blind, sham-controlled trial was carried out in 21 patients, with malformations of cortical development and refractory epilepsy, who underwent five consecutive sessions of low-frequency rTMS.67 rTMS decreased significantly the number of seizures in the active group compared with the sham rTMS group (p<0.0001), and this effect lasted for at least 2 months. Further, preliminary cognitive evaluation suggested improvement in some aspects of cognition in the active rTMS group, although, again, validation of this approach in further studies is warranted.

There is also evidence that transcranial direct current stimulation reduces neuronal excitability68 and brings about a seizure reduction in animal models. Clinical studies conducted to date, however, have shown mixed results.69,70

The autostimulation feature of the latest AspireSR® VNS therapy device (Cyberonics, Inc., Houston, TX, US) works in a closed-loop modality, and is based on the premise that heart rate increases in over 80 % of all seizures.71 AspireSR senses heart beats and a cardiac-based seizure detection algorithm continuously analyses changes in relative heart rate. Stimulation is delivered when the heart rate increases above a programmable threshold. This algorithm was studied in Europe (E-36 study)72 and the US (E-37 study) and 51 patients admitted to the Epilepsy Monitoring Unit (EMU) for seizure and electrocardiogram (ECG) recording were evaluated during their EMU stay and followed-up over a long-term period. The primary endpoint of ≥80 % sensitivity for at least one algorithm setting was met with a very low false positive rate (maximum 7/hour). Significant improvements in clinical outcomes were achieved including seizure cessation, reduced seizure duration and severity and improved QoL.

Conclusions

- DRE has a major negative impact and increases risks for patients.

- While there is a clear definition of DRE there are often significant delays in identifying and evaluating patients with DRE.

- There is a major treatment gap in patients with DRE that needs to be addressed (see Figure 2).

- Mood, memory disturbances and seizure-related injuries adversely affect quality-of-life in patients with DRE. Addressing depressive comorbidity and reducing the burden of AED toxicity is likely to be far more beneficial than interventions aimed at reducing the frequency of seizure alone.

- Several non-pharmacologic options (diet, devices) exist for patients with drug-resistant epilepsy who are not candidates for epilepsy surgery

- Long-term retention rates are much higher for VNS compared with AEDs (see Figure 1), and seizure outcomes continue to improve over longer follow-up periods.

- Closed-loop VNS is available and early data show great promise in reducing seizure burden and improved quality of life.