Restless legs syndrome (RLS), or Willis–Ekbom disease (WED), is a sensorimotor disorder having well-known standardised diagnostic criteria1 that have been revised recently by the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group.2 The genetic basis of RLS has not been definitively established,3 but the most important biochemical findings are dopaminergic dysfunction and iron deficiency.4

The interest for RLS is relatively recent, with the number of publications on this issue growing exponentially. A current PubMed search shows 3,601 papers on this topic from 1966 to today, 2,967 published from 2000 to 2015 (541 from 2000 to 2004; 1,045 from 2005 to 2009; 1,381 from 2010 to February 24, 2015). Many of these reports are related to the development of efficacious drugs – especially dopamine agonists, the most effective for the treatment of RLS/WED.

In this review, we summarise the main findings related to neuropharmacological aspects of idiopathic RLS (iRLS) and to nonpharmacological therapies

Search Strategy

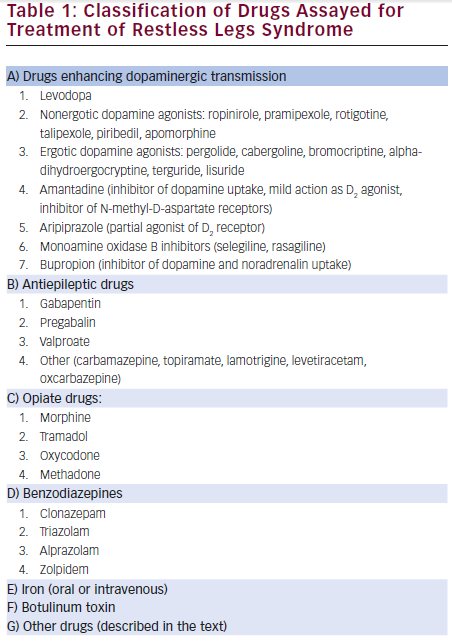

References for this review were identified by searching PubMed from 1966 until February 25, 2015. The term “restless legs syndrome” was crossed with “pharmacology”, “neuropharmacology”, “treatment” and “therapy”. This search retrieved 2,192 references, which were individually examined, with related references of interest (n=274) selected. According to this search, drugs essayed for the treatment of iRLS are summarised in Table 1.

Drugs Enhancing Dopaminergic Neurotransmission

Levodopa

The results of studies on the efficacy of levodopa (the precursor of dopamine) in the treatment of iRLS are summarised in Supplementary Table 1. All these studies, independent of their design, showed significant improvement of RLS symptoms and/or periodic limb movements (PLMS).5– 17 Some of them mentioned the presence of a rebound phenomenon in the last part of the sleep time when using regular-release levodopa,7,14–16 which was improved by the use of sustained-release levodopa alone15,16 or combined with regular-release levodopa.14

Stiasny-Kolster et al.18 validated the so-called “levodopa test” for the diagnosis of RLS. This consisted of the application of a single dose of benserazide/levodopa 25/100 mg with a subsequent 2-hour period of observation, considering as “positive” a 50 % improvement in “symptoms in the legs” (sensitivity 80 %; specificity 100 %) and “urge to move the legs” (sensitivity 88 %; specificity 100 %) in 15-minute intervals.

Guilleminault et al.19 investigated the rebound phenomenon in 20 RLS patients treated with a bedtime dose of controlled-release carbidopa/levodopa 25/100 mg. Even though at 4 to 7 weeks none of the patients exhibited subjective RLS symptoms, and PLMS reduced by 80 % after 11±2 months of follow-up, seven subjects reported the re-emergence of disturbing RLS symptoms between 8:00 pm and 11:00 pm. This rebound phenomenon disappeared in four patients after drug withdrawal (with reappearance of the RLS symptoms) and reappeared after its reintroduction. Rebound phenomenon was adequately controlled in the seven patients after placing them on two doses of controlled-release carbidopa/levodopa 25/100 mg (at night and in the morning). The other important long-term side effect of levodopa (and dopamine agonists) is the augmentation phenomenon, defined as a loss of circadian recurrence with progressively earlier daily onset and increase in the duration, intensity and distribution of symptoms.20 This complication has been found in up to 82 % of patients treated with levodopa, mainly in those having more severe symptoms and in those using higher doses of this drug.21 Vetrugno et al.22 showed a temporal relation between low plasma levodopa levels and signs of augmentation in a patient, with improvement of RLS symptoms 75 minutes after oral levodopa administration and reappearance of these symptoms after 3 hours, coinciding with rapid rise and fall of plasma levodopa concentrations.

García-Borreguero et al.23 studied circadian changes in dopaminergic function by means of measurement of responses of growth hormone (GH) and prolactin (PRL) to two acute administrations of carbidopa/levodopa 50/200 mg (one at 11 am and other at 11 pm) in 12 iRLS patients and 12 healthy controls. Though basal plasma GH and PRL levels were similar in both groups, nocturnal administration of levodopa induced a more pronounced inhibition of PRL release and an increase in GH secretion, PRL plasma levels being correlated with the PLM index in polysomnography. This group determined dim light melatonin onset (DLMO), a marker of circadian phase, in eight previously untreated iRLS patients before and after a 3-week open-label treatment with carbidopa/levodopa 100/400 mg and showed a significant anticipation of DLMO after levodopa treatment.24 These findings suggest increased circadian variations in dopaminergic function in iRLS patients.

Two systematic reviews, including nine eligible trials, concluded that the short-term treatment of RLS and PLMs with levodopa showed efficacy and safety; however, the assessment of the usefulness of long-term treatment and the development of the augmentation phenomenon has not been investigated sufficiently.25,26

Shariff27 reported increased duration of the action of carbidopa/levodopa induced by entacapone (a peripheral inhibitor of catechol-ortho-methyltransferase [COMT]) in a patient who had RLS. Afterwards, Polo et al.28 confirmed that the association of entacapone to carbidopa/levodopa was useful to prolong symptom control in a randomised, double-blind, crossover study with polysomnography.

Dopamine Agonists

The studies of ropinirole,29–41 pramipexole,42–73 rotigotine,74–85 pergolide86–94 and cabergoline,95–101 respectively, in the treatment of iRLS are summarised by Supplementary Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6. All these studies comparing dopamine agonists with placebo showed a significant improvement in the severity of RLS (assessed with several scales, being the most frequently used the International RLS Study Group Scale), in the IRLS frequency of “responder” rates (improvement in >50 %), in the Clinical Global Impression Improvement (CGI-I) and Patient Global Impression Improvement (PGI-I), in the quality of life (QoL) and in polysomnographic (PSG) measurements.

The efficacy, safety and tolerability of sumanirole (a highly selective D2 agonist) has been assessed in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised, parallel-group, dose-response study involving 270 patients with iRLS randomised to sumanirole 0.5,1.0, 2.0, 4.0 mg or placebo.102 Even though this drug was well tolerated, only the dose of sumanirole 4.0 showed improvement in the International Restless Legs Scale-10 (IRLS-10) compared with placebo or with lower doses of sumanirole. PSG variables, especially the periodic leg movements index (PLMI), improved in a doserelated manner during sleep.102

Other dopamine agonists, including bromocriptine,103 talipexole,104 amantadine,105 alpha-dihydroergocryptine,106 piribedil,107 terguride,108 aripiprazole,109 apomorphine (subcutaneous)110–112 and lisuride (transdermal)113,114 have shown efficacy in the treatment of RLS, most of them in open-label studies having a low sample size.

Two studies showed higher efficacy of pergolide86 and cabergoline101 in comparison with levodopa. In particular, the study with cabergoline was of higher duration, involved an important number of patients and found less frequent augmentation for cabergoline than for levodopa.101 Improvement of RLS obtained with pramipexole did not differ significantly from that obtained with levodopa60 or with ropinirole67 in two comparative studies.

Several systematic reviews and/or meta-analysis on the efficacy or dopamine agonists in the short-term treatment of RLS have been reported to date:

(a) A systematic review and meta-analysis of six randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trials involving 1,679 RLS patients (835 receiving immediate-release ropinirole and 844 placebo) showed evidence that ropinirole improved sleep quality and adequacy, and decreased daytime somnolence, in RLS patients.115

(b) An evidence-based review showed a clear evidence of the effectiveness of pramipexole in studies published up to 2004, both in reduction of the leg movements associated with RLS and in improvements in both the International Restless Legs Syndrome Rating Scale (IRLSSGRS) and in the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scores, with moderate evidence of improving sleep quality.116

(c) A meta-analysis of studies published until 2013 showed a favourable effect of pramipexole in comparison with placebo in IRLSSGRS and sleep quality (p<0.00001 each), with nausea (RR 1.82–3.95; p<0.001) and fatigue (RR 1.14–2.93; p=0.013) the most common adverse effects and, in general, good tolerance to pramipexole.117

(d) Quilici et al.118 reported data from a meta-analysis of studies on the efficacy and tolerability of pramipexole and ropinirole published up to 2008. Both dopamine agonists were significantly better than placebo in improving IRLSSGS scores and CGI-I scale; pramipexole showed a higher incidence of nausea than placebo; and ropinirole showed a higher incidence of nausea, vomiting, dizziness and somnolence than placebo. The indirect comparison of pramipexole and ropinirole showed significantly higher reduction in IRLSSGS score and higher improvement in CGI-I scale, as well as lower incidence of nausea, vomiting and dizziness for pramipexole.

(e) Bogan119 reviewed all clinical trials of rotigotine in RLS and concluded that this drug was efficacious in improving RLS symptoms and was generally well tolerated, with low risk of developing clinically significant augmentation.

(f) Several systematic reviews assessing the efficacy of dopamine agonists as a generic group concluded that these drugs showed moderate efficacy in short-term studies (up to 7 months) in improving the IRLSSGS score and CGI-I scores and in QoL scales scores, a higher frequency of IRLSSGS “response” (defined as a >50 % reduction in IRLSSGS score),120–125 a higher improvement in QoL scales scores120,122–126 and an important reduction in PLMI,120,122–125 though with a significantly higher frequency of adverse effects and likelihood of dropout than patients under placebo.120–122 Active controlled and long-term studies are scarce.122,123

Three studies analysed the results of long-term treatment of RLS (5 years or longer) with dopamine agonists:

(a) Ondo et al.,127 in a 7-year longitudinal retrospective study, showed that efficacy of dopamine agonists was maintained across time but with a moderate significant increase in dose and presence of augmentation (usually modest) in 48 % of patients, most of them having a positive family history of RLS and lack of neuropathy in nerve conduction studies.

(b) Silver et al.,128 in a 10-year longitudinal retrospective study of RLS patients treated in a tertiary care centre with pramipexole or pergolide, found annual rates for discontinuing treatment of 9 % for pramipexole and 8 % for pergolide, with annual rates of augmentation of 7 % for pramipexole and 5 % for pergolide. Only 58 % of patients under pramipexole and 35 % under pergolide continued the treatment for more than 5 years.

(c) Data from a prospective open extension period of a preceding doubleblind placebo-controlled trial with rotigotine80 are summarised in Supplementary Table 4.

The effect of controlled withdrawal of dopamine agonists has been studied for pramipexole by Trenkwalder et al.129 in 150 RLS patients who had responded to pramipexole (mean dose 0.50 mg) during at least 6 months and were randomised to receive placebo or to continue receiving pramipexole 0.125–0.75 mg/day for 3 months. A total of 88.5 % patients randomised to placebo versus 20.5 % to pramipexole, worsened more often and more quickly in a CGI-I (p<0.0001). Augmentation was not reported as side effect by any of these patients.

The response of RLS symptoms to ropinirole seems to be independent of age130 and serum ferritin levels.131 Both ropinirole132 and pramipexole65 improved depressive symptoms in RLS patients. Dopaminergic drugs can be related to pathological gambling (7 %) and increased sexual desire (5 %) in RLS patients.133

As previously commented, the augmentation phenomenon is an important long-term side effect of dopamine agonists. Several studies addressed the frequency of augmentation in patients under dopamine agonist treatment:

(a) Augmentation was present in 3.5 % of RLS patients under ropinirole and in less than 1 % of patients under placebo during the doubleblind phase, as well as in 3 % of RLS under ropinirole during the open-label phase, of a study involving 404 patients in a 26-week double-blind flexible-dose treatment with ropinirole or placebo, followed by an open-label phase involving 269 of these patients under ropinirole.134

(b) Ferini-Strambi135 reported augmentation in 8.3 % of 60 RLS patients under pramipexole therapy in an open-label clinical series, this sideeffect being more frequent in patients who had secondary RLS (4/21) than in those who had iRLS (1/39). Augmentation was unrelated to severity of RLS or with doses of pramipexole. Silber et al.136 reported augmentation in 33 % of 60 RLS patients, which increased to 48 % in 50 patients with a long-term follow-up period under pramipexole.137 Finally, Winkelmann et al.138 reported augmentation in 32 %, and tolerance in 46 %, of 59 RLS patients treated with pramipexole

(c) Beneš et al.139 retrospectively reviewed data from two doubleblind placebo-controlled 6-month trials involving 745 rotigotine and 214 placebo subjects, as well as from two open-label 1-year trials involving 620 rotigotine subjects looking for the frequency of augmentation according to the Max Planck diagnostic (MPD) criteria,140 which included usual time of RLS symptom onset each day, number of body parts having RLS symptoms, latency to symptoms at rest, severity of the symptoms when occurring and effects of dopaminergic medication on symptoms. They found that 8.2 % of subjects (11 subjects under rotigotine and one under placebo) reporting clinically relevant augmentation in the double-blind trials and 9.7 % (2.9 % having clinically relevant augmentation) fulfilled MPD criteria for augmentation.

(d) Allen et al.141 assessed the frequency of augmentation, using National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines, in a community sample of 266 patients who had RLS under long-term dopamine agonist therapy. A total of 20 % of patients were classified as having definitive or probable augmentation, the main risk factors being the presence of most frequent RLS symptoms pre-treatment, greater severity of RLS symptoms pre-treatment and longer treatment duration.

(e) Two studies that reported augmentation in 10.65 % of 338142 and 11.7 % of 162 RLS patients143 who had long-term dopaminergic therapy showed significantly lower serum ferritin levels in patients who had augmentation than in patients who did not experience this side effect.142,143

Studies using transcranial magnetic stimulation showed reduction in the short latency intracortical inhibition144 and shortening in the cortical silent period145 (both inhibitory phenomena) in RLS patients, reversed with cabergoline treatment.144,145 The amplitude of the motor evoked potential after a rest period was increased after pramipexole treatment, suggesting delayed facilitation.146

In the evaluation of results of clinical trials involving RLS patients, it is very important to consider the placebo responses. This issue has been addressed by De la Fuente-Fernández,147 who, after analysing two large multicentre trials on the efficacy of rotigotine in RLS, showed that in RLS trials dopaminergic pretreatment should condition the interpretation on the apparent effect of new dopaminergic drugs by decreasing the placebo effect in the placebo arm but not in the active treatment arm. Moreover, Fulda et al.148 reported a response rate for placebo of around 40 % in a pooled study of 24 eligible trials of RLS treatments.

Monoamine Oxidase B Inhibitors

One open-label study described a significant improvement (p<0.0005) of PLMI during sleep in a cohort of 31 RLS patients treated with selegiline,149 and an anecdotal report described improvement of RLS symptoms in a patient with an 8-year history of RLS who developed Parkinson disease 7 years later.150

Bupropion

This antidepressant, which inhibits dopamine and noradrenalin reuptake, has been reported to improve RLS symptoms in some patients.151,152 A double-blind, randomised, controlled trial involving 29 patients who had moderate to severe RLS receiving bupropion 150 mg/day and 31 controls receiving placebo showed a significant improvement in IRLSSGRS score for bupropion at 3 weeks (p=0.016), but the difference did not reach statistical significance at 6 weeks.153

Antiepileptic Drugs

Gabapentin

Supplementary Table 7 summarises the studies on the efficacy of gabapentin (gabapentin enacarbil in most of them) in the treatment of RLS.154–168 Most of them showed a significant and considerable efficacy of different doses of gabapentin in relation with placebo. Two studies showed maintenance of the efficacy over the long term,163,166 and others demonstrated similar efficacy for gabapentin as for ropinirole.158

VanMeter et al.169 analysed the summarised results (efficacy and safety) of three 12-week studies, involving 760 patients, using gabapentin 600 (163 patients), 1,200 (269 patients), 1,800 (38 patients) and 2,400 mg/ day (45 patients) or placebo (245 patients). They found a significant short-term improvement in IRLSSGRS score (13.6±0.71 versus 9.3±0.55; p<0.0001), and in CGI-I responder rate (70.2 % versus 42.2 %; p<0.0001) for gabapentin 600 mg compared with placebo, with similar benefits for the three higher doses of gabapentin. However, most studies suggest that the most effective dose, for improving both RLS symptoms and associated sleep disturbances, is 1,200 mg/day.170

Sun et al.,171 in a mixed treatment comparison of gabapentin enacarbil, pramipexole, ropinirole and rotigotine (compared with placebo) in moderate to severe RLS, in which they identified 28 clinical trials, showed similar efficacies for the four active drugs assessed by changes in IRLSSGRS scores, IRLS responders, CGI-I responders and RLS-6 scores (with the exception of higher changes in IRLSSGRS for rotigotine than for ropinirole).

Pregabalin

The efficacy of pregabalin in the treatment of RLS was first reported in a preliminary study involving 16 secondary RLS (most of them resulting from neuropathy) and three iRLS, which showed subjective improvement in RLS symptoms in 16 patients (the other three withdrew the drug because of side effects), with a mean daily dose of 305±185 mg during a mean of 217 of follow-up.172

A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial with PSG control involving 58 patients (selected from 98 patients who underwent a singleblind phase with placebo) showed a higher IRLS responder rate (63 % versus 38.2 %; p<0.05); a greater improvement in CGI-I, RLS-6 scale and Medical Outcomes Study Sleep Scale (p<0.01 each); a greater reduction in the PLMI (p<0.001) and improvement in sleep architecture with an increase in slow wave sleep (p<0.01) and decrease in wake after sleep onset and stages 1 and 2 (p<0.05) for pregabalin (mean dose 322.50±98.77 mg/day) than for placebo.173

A 6-week, six-arm (pregabalin 50, 100, 150, 300 or 450 mg or placebo), randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled dose-response study involving 137 patients who had moderate to severe iRLS showed a significantly higher improvement in the IRLSSGRS score for pregabalin (with mean dose of 123.9 mg providing 90 % efficacy), as well as a higher proportion of CGI-I responders for 300 and 450 mg of pregabalin.174

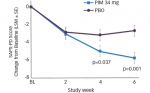

Two further studies compared the efficacy of pregabalin with pramipexole. García-Borreguero et al.,175 in a 4-week randomised, doubleblind, crossover trial with PSG, involving 85 patients with moderate to severe iRLS who used pregabalin 300 mg/day, pramipexole 0.5 mg/day and placebo, showed a significant improvement in sleep maintenance (p<0.0001) and in the number of awakenings after sleep onset (p<0.0001) and an increase in subjective total sleep time (p<0.0001) and in slow wave duration (p<0.0001) for pregabalin than for pramipexole and placebo, as well as a significant reduction in PLMAI compared with placebo (p<0.0001) that was similar to that obtained with pramipexole.

Allen et al.,176 in a 52-week randomised, double-blind trial assigned 719 patients to pregabalin 300 mg/day, pramipexole 0.25–0.5 mg/day or 12 weeks of placebo followed by 40 weeks of active treatment with these drugs. Patients treated with pregabalin showed greater reduction IRLSSGRS score (p<0.001) and higher percentage of CGI-I than those treated with placebo (71.4 % versus 46.8 %; p<0.001) at 12 weeks, and the rate of augmentation over 40–52 weeks was significantly lower with pregabalin than with pramipexole 0.5 mg (2.1 % versus 7.7 %; p=0.001) but not than with pramipexole 1 mg (5.3 %; p=0.08).

Other Antiepileptic Drugs

Slow-release valproic acid 600 mg showed similar efficacy to slow-release 50/200 benserazide/levodopa in reducing PLMS and PLM arousal index, with a higher decrease of intensity and duration of RLS symptoms for valproic acid (p=0.022), in a randomised, placebo-controlled, crossover double-blind study involving 20 RLS patients.177

Data from a preliminary study with six patients showed improvement in several patients with carbamazepine,178 and a double-blind study involving 174 patients showed a significant improvement of RLS symptoms both for placebo and carbamazepine (p<0.01 for both), with a significantly higher efficacy for carbamazepine (p=0.03).179,180

Several anecdotal reports described improvement or RLS symptoms with topiramate,181 lamotrigine,182 levetiracetam183,184 and oxcarbazepine.185

Opiates

The first observations of improvement of RLS186–189 and of PLMS190 with opiates including oxycodone186 were reported approximately 30 years ago. Moreover, intrathecal or peridural administration of morphine has shown relief of RLS symptoms in several patients with severe RLS.191–196 RLS has been described as a transient complication of opiates withdrawal,197 although treatment with the opioid antagonist naloxone worsened neither RLS symptoms nor periodic movements during sleep and did not alter adrenocorticotropic hormone, cortisol, PRL or GH levels in drug-naive RLS patients.198

The efficacy of tramadol (50–150 mg/day in an evening dose) has been assessed in an open-label study with a follow-up period of 15–24 months, involving 12 RLS patients, in which 10 patients reported a significant improvement, other slight amelioration and other no effect, and none reported major tolerance problems.199 Several patients under tramadol therapy for RLS showed augmentation200,201

The efficacy of oxycodone was assessed in two studies. A 2-week randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial involving 11 RLS patients showed significant improvement in leg sensations (p<0.009), motor restlessness (p<0.006) and daytime alertness (p<0.03), and reduction in PLMS/hour sleep (p<0.004) and in the number of arousals/hour sleep (p<0.009), for oxycodone (mean dose 15.9 mg/day) in comparison with baseline or placebo.202

A further multicentre, 12-week randomised, double-blind, placebocontrolled trial followed by a 40-week open-label extension phase involved 276 patients who had severe RLS (mean IRLSSGRS score 31.6±4.5 points), who were randomised to prolonged release oxycodone/ naloxone (5/2.5 mg/12 hours as initial doses, up to a maximum of 40/20 mg/12 hours, 132 patients) or to placebo (144 patients). In the extension phase, the 190 patients enrolled also used oxycodone/naloxone 5/2.5 mg/12 hours as initial doses, up to a maximum of 40/20 mg/12 hours. At 12 weeks, the mean improvement in IRLSSGRS scores was superior for the prolonged release oxycodone/naloxone group (16.5±11.3 versus 9.4±10.9 for placebo; p<0.0001). The IRLSSGS score at the final of the extension phase was 9.7±7.8. Seventy-three per cent of patients of oxycodone/naloxone versus 43 % of the placebo group in the doubleblind phase and 57 % of patients during the extension phase reported adverse events, but only in 2 % under oxycodone/naloxone were they serious (vomiting with concurrent duodenal ulcer, constipation, subileus, ileus, and acute flank pain).203

The efficacy of the synthetic opiate methadone in the treatment of RLS was first reported by Ondo,204 who administered methadone 5–40 mg/day (mean 15.6±7.7 mg/day) to 27 RLS patients resistant to dopaminergic therapy as added-on therapy. Seventeen patients remained on methadone therapy 15.5±7.7 mg/day during 23±12 months (two died because of chronic renal failure, and five withdrew from treatment because of adverse events, two for lack of efficacy, and one for other reasons) and reported a 75 % reduction of their symptoms, with no cases of augmentation. Silver et al.,128 in a 10-year longitudinal assessment of methadone in the treatment of RLS involving 76 patients treated with this drug, described a 15 % of withdrawal rate during the first year of treatment (sedation in 4 %, depression and anxiety in 3 %, altered consciousness in 3 % and lack of efficacy in 3 %) and absence of augmentation during the follow-up period.

Finally, Walters et al.205 analysed the medical records of 493 patients with RLS. One-hundred and thirteen patients had been on opioid therapy. Thirtysix of these patients were under opiate drugs in monotherapy (23 of them resistant to dopaminergic or other treatments, 20 of them continued in opiate monotherapy during nearly 6 years, only one of the 16 withdrawals was related with addiction or tolerance) and 77 patients used opiates in combination with other drugs. Decrease in PLMS index, PLMS arousal index and PLM while awake index, as well as improvement in sleep parameters (increase in stages 3 and 4 and REM sleep, total sleep time, sleep efficiency and decrease in sleep latency) assessed by PSG in seven patients, was maintained at 7 years of monotherapy.

Benzodiazepines

After the first description of improvement or RLS with clonazepam by Boghen,206 two randomised double-blind crossover trials versus placebo involving short series of RLS patients207,208 confirmed these findings showed efficacy of clonazepam 0.5–2 mg in reducing the PLMS index in PSG studies.209–211

There have been described improvements of RLS symptoms 212 and in PLMS with triazolam,213,214 as well as of RLS symptoms with alprazolam215 and zolpidem216 based on anecdotal reports or on short series of patients.

Iron

Studies on the efficacy of oral and intravenous supplements or iron in RLS (most studies involved patients with low-normal serum ferritin levels) are summarised in Supplementary Table 8.217–229 Although retrospective chart reviews suggested short-term improvement of RLS with oral iron supplements,219,220 the results of short-term randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies were te opposite,213,218 and other short-term studies showed similar efficacy than pramipexole.219

Regarding the efficacy or intravenous iron, the results of the studies summarised in Supplementary Table 8, despite their different designs, suggest short-term improvement of RLS symptoms that are not maintained at long-term follow-up periods.

Botulinum Toxin A

Rotenberg et al.230 reported, in an observational study involving three patients, improvement of refractory RLS with botulinum toxin A (BTXA). All patients were injected in the areas of maximal discomfort in both legs, and one of them in lumbar paraspinal muscles as well. Improvement of RLS symptoms was maintained during 10–12 weeks. In contrast, Ghoyareb and Burbaud231 reported lack of improvement of RLS symptoms in another observational study involving three patients (with evaluations at 2, 4 and 6 weeks), and data from a 4-week single-arm, open-label pilot trial involving a short series of patients showed improvement in the IRLSSGRS score, a visual analogue scale measuring pain and PGI-I.232

A double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial involving seven patients (BTXA was injected in quadriceps femoris [40 units], tibialis anterior [20 units], gastrocnemius [20 units] and soleus [10 units]) showed lack of improvement in IRLSSGRS and in CGI-I scores at the fourth week.233 Finally, an optimal two-stage, phase II exploratory, open-label, noncomparative trial involving 27 patients who had moderate to severe RLS and who received a series of 20 intradermal injections of 0.05 ml of BTXA showed improvement in the IRLSSGRS score only in six patients, maintained during 46 days.234

Other Pharmacological Therapies

A 1-week double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study involving 10 RLS patients showed improvement of low-dose hydrocortisone (40 mg) compared with placebo (p=0.032) in the severity of sensory leg discomfort during a suggested immobilisation test (SIT).235

A double-blind placebo-controlled crossover trial with hydroquinone (200 mg in the evening and 200 mg before going to bed) involving 68 patients (completed by 59 patients) found lack of improvement using a daily questionnaire and a SIT.236

An 8-week prospective, triple-blinded, randomised, placebo-controlled, parallel design study involving 37 RLS patients showed significant improvement of sleepiness (p=0.01) and IRLSSGRS (p=0.02) with the herbal valerian (800 mg) compared with placebo.237

Several anecdotal reports or open-label studies with short series of patients described improvement of RLS symptoms by the following drug groups:

(a) Drugs acting on cholinergic system: cigarette smoking (attributed to stimulation of nicotine acetylcholine receptors),238 varenicline (partial agonist at the alpha4-beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor),239 physostigmine (a reversible cholinesterase inhibitor,240,241 orphenadrine (an anticholinergic drug of the ethanolamine antihistamine class)242 and hydroxyzine (H1 antihistaminic with anticholinergic properties).243

(b) Drugs acting on adrenergic system, such as the α2-adrenergic agonist clonidine,244 though other authors reported no improvement with this drug.245

(c) Antidepressants, such as amitriptyline,246 and selective serotonin receptor uptake inhibitors (SSRI).246 Although RLS it is a well-known adverse effect of SSRI, a retrospective study involving 43 depressed patients having pre-existent RLS symptoms found reduction in 58 %, and abolishment of RLS symptoms in 12 %, of cases, with only 12 % reporting worsening.247

(d) Inhibitors of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, e.g. ketamine.248

(e) Hormones such as alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH).249

(f) Vitamin E,250 niacin,251 vitamin D,252 magnesium253,254 or selenium supplements.255

(g) Nitroglycerin administered sublingually256 or in patches.257

(h) Herbs,258,259 including yokukansan260 and Saint John’s wort.261

The adenosine A2A receptor istradefylline did not show beneficial effect,262 and melatonin caused worsening263 of RLS symptoms in short open-label studies.

Non-pharmacological Therapies

Acupuncture

Cui et al.264 reported a systematic review on the role of acupuncture in the therapy of RLS up to 2007. Most of the controlled trials were obtained from Asiatic Databases, and only two out of 14 trials with 170 patients met the inclusion criteria. One trial showed no significant differences between acupuncture and medications, and the other showed significant improvement with the combination of acupuncture, massage and mediations in comparison with massage and medications alone, but there were no differences in the duration of RLS symptoms. The efficacy of acupuncture was not sufficiently evident.

Wu et al.,265 in an observational study involving 158 RLS patients (79 assigned to acupuncture combined with TDP radiation and 79 to levodopa), described higher efficacy of acupuncture combined with TDP radiation (91.1 % versus 30.4 % of improvement rate). Finally, Cripps et al.,266 in a retrospective observational study, showed a significantly higher improvement in RLS severity in 16 patients without previous dopaminergic treatment than in three treated previously using these drugs.

Exercise

A 12-week randomised, controlled trial involving 41 iRLS patients (28 of them available, 23 completing the trial, 11 of them have been randomly

assigned to exercise and 12 serving as controls) showed significant improvement in the IRLSSGRS scores (p=0.001) and in a ordinal scale (p<0.001) for the group randomly assigned to the exercise programme (aerobic and lower-body resistance training 3 days per week).267

Yoga

An 8-week observational study with a Iyengar yoga program, involving 13 iRLS patients (completed by 10 of them) showed significant improvement in the IRLSSGRS in an RLS ordinal score, which was correlated with increasing minutes of homework practice per session and with total homework minutes, as well as significant improvement in sleep, perceived stress and mood scales.268

Traction Straight Leg Raise Techniques

The effects of this technique have been assessed in a 15-day observational study involving a cohort of 15 patients who had iRLS (13 completed the study). There were significant improvements, compared to baseline, in IRLSSGRS score (63 % of reduction; p<0.05), in an RLS ordinal scale, and in a global rating of change.269

Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic and Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation

A recent prospective, double-blind, randomised study involving 19 iRLS patients (11 randomised to rTMS and eight with sham stimulation) showed a significant reduction in IRLSSGRS scores for the group treated with rTMS after the fifth to the 10th sessions. Moreover, five patients of the sham stimulation who afterwards received real rTMS showed a significant improvement as well.270

A 2-week double-blind, randomised, sham-controlled performed in 33 drug-naive females who had RLS using cathodal, anodal and sham tCDS with electrodes on the sensorimotor cortex, making assessments at baseline, 3 days and 13 days, showed lack of improvement in IRLSSGRS scores, CGI-I, PGI scale, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, Medical Outcome Study sleep subscale and Beck depression inventory.271

Conclusions

Dopamine agonists should be considered the first-line drugs for the treatment of iRLS, because most of them have shown a significant improvement compared with placebo (although the degree of improvement with placebo in many of the clinical trials is relatively high).147,148 However, several considerations should be noted:

(a) Most of the studies with dopamine agonists have evaluated the results after short-term follow-up periods. Although studies with follow-up periods longer than 5 years described a high withdrawal rate, the effect of dopamine agonists is maintained across the time in an important percentage of patients.80,127,128

(b) Many of the clinical trials have been performed with short-acting dopamine agonists (with the exception of those performed with cabergoline and rotigotine). Although in the clinical setting it is possible that the sustained-release forms of ropinirole and pramipexole might be more useful than the standard-release ones (Jiménez-Jiménez et al., unpublished data), there are (surprisingly) no reports concerning this matter.

(c) Ergotic derivatives (mainly cabergoline and pergolide), though effective, are not recommended because of the risk of developing cardiac valve fibrosis.

Levodopa should be considered as a good option for those patients who developed adverse effects with dopamine agonists. Although its efficacy is similar to that of pramipexole,60 and lower than that of pergolide86 and cabergoline101 (which are not generally recommended because of the risk of cardiac valve fibrosis), the risk for development of rebound or augmentation phenomena is higher than that with dopamine agonists. It is possible that the frequency of these complications could be lessened with the use of sustained-release preparations,19 but to our knowledge, there are no comparative studies between sustained and standard release preparations of levodopa.

Gabapentin should be considered, as with dopamine agonists, as a first-line therapy for iRLS, with a similar degree of efficacy to ropinirole, pramipexole and rotigotine.171 The same observation could be made of pregabalin, which was slightly superior to pramipexole in improving several sleep parameters in short-term studies175 and showed similar efficacy to pramipexole (but with less risk of augmentation) in long-term studies.176 Although studies with valproic acid177 and carbamazepine179,180 are scarce, these might be useful as alternative treatments when first-line drugs have not been useful.

Opiate drugs, mainly oxycodone or methadone, alone or in combination, have shown efficacy in the control of RLS symptoms,202–205 maintained across time in many patients,128,204,205 with no cases of augmentation.128,204 Although patients under opiate treatment risk developing addiction and tolerance, the withdrawal rate reported for these complications was approximately 6 %.205 These drugs should be considered as an alternative therapy for patients who have RLS who have been unresponsive to dopamine agonists or antiepileptic drugs.

Benzodiazepines, in particular clonazepam, have shown efficacy in short series of patients both in the improvement of RLS symptoms and, especially, in reducing PLMS. This drug should be considered as a useful add-on therapy in patients who have high PLMI.

Though the results surrounding the oral supplementation of iron to control RLS symptoms are controversial, the efficacy of intravenous iron is well established, and it should be considered as a useful add-on therapy for refractory RLS. Unfortunately, the duration of the pharmacological effect is short.

The possible role of valerian (a herb having a good profile of side effects), which has shown short-term improvement of RLS symptoms in a triple-blinded, placebo-controlled study with a low sample size,237 seems to be promising, though it awaits confirmation with long-term studies involving greater numbers of patients. Other drugs have not proved their efficacy in the treatment of RLS.

Among non-pharmacological therapies, preliminary studies on exercise,267 yoga,268 traction straight leg raise techniques269 and repetitive transcranial stimulation270 have shown possible efficacy, though transcranial direct current stimulation was not useful271 and the role of acupuncture remains to be determined.

The main conclusions of this review are in the same line as those of several guidelines published in recent years.272–278 A proposed algorithm for the management of iRLS is depicted in Figure 1.