Cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) is a rare condition.1–3 While thrombophilias, contraceptive pill, hormonal replacement therapy, and neoplasms are well-established predisposing factors, steroid use is a less-common possible risk factor, particularly with regard to anabolic androgenic steroids (AAS).1–4

We intend to describe what is known about AAS and present a case of CVT associated with AAS use in a young patient.

Case presentation

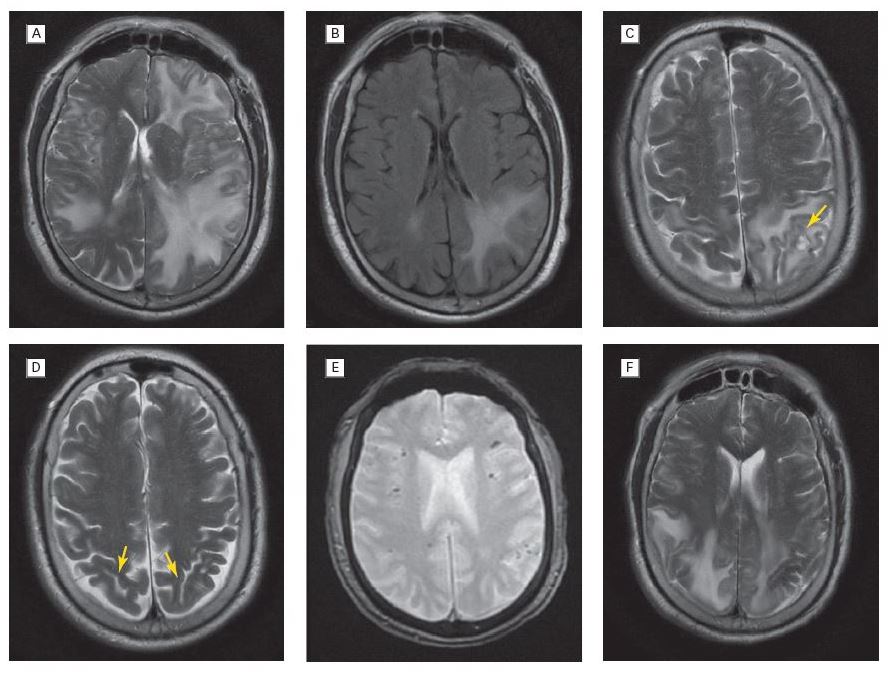

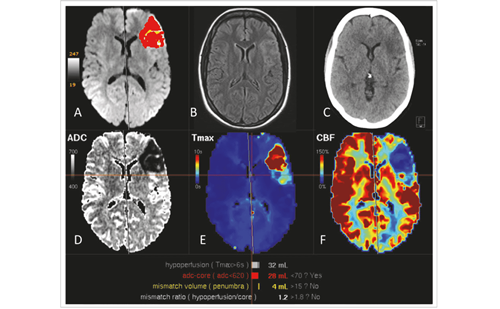

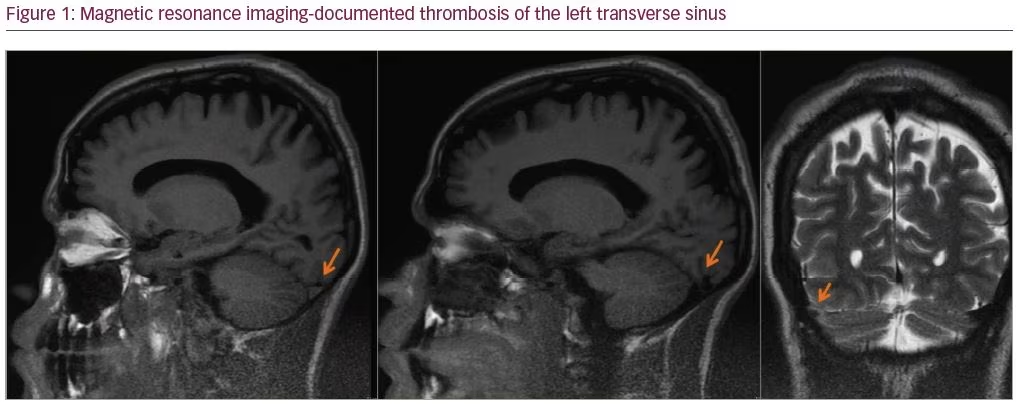

A 27-year-old man was admitted with a severe holocranial headache, nausea, vomiting, photophobia, and diplopia, which had begun 3 days before. He had no relevant past medical antecedent, no previous migrainous headache, nor any pertinent family history of hypercoagulability. However, he had been taking AASs for 1 year to increase muscle mass (intramuscular testosterone weekly, in addition to 400 mg of oxymetholone and 300 mg of nandrolone daily). On examination he had papilledema and bilateral sixth nerve palsy. Blood tests revealed thrombocytosis with 263,000 platelets/mm3 without other alterations on hemogram like polycythemia. Computed tomography venography documented thrombosis of the left transverse and sigmoid sinuses (Figures 1 and 2). The workup ruled out other causes of CVT, such as hereditary thrombophilia, infection, or neoplasia. Autoimmune diseases and vasculitis syndromes were ruled out by appropriate investigations (e.g., screening for antinuclear antibodies [ANA], antiphospholipid antibodies [APLA], antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies [ANCA], cytoplasmic and perinuclear ANCA [cANCA and pANCA]). Vitamin B12, folic acid, and serum homocysteine levels were normal.

The patient was started on anticoagulant therapy with enoxaparin 1 mg/kg every 12 hours. A combination of analgesics and acetazolamide were introduced because of refractory headache. The follow-up magnetic resonance imaging, performed 6 months later, showed resolution of thrombosis.

Discussion

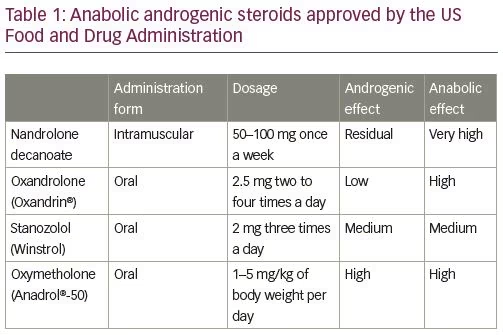

There are two main types of steroids, namely corticosteroids and AASs; the latter carrying a greater risk of thrombosis. Since their synthesis in 1935, AASs began to be widely consumed: firstly, by the elite athletes to improve their sports performance, and then by the general population, especially the younger, with the purpose of increasing muscle mass as well as a recreational drug, disregarding their harmful effects.5–6 In fact, AASs are synthetic derivatives of testosterone with a strong anabolic effect and only residual androgenic action.7 For that reason, they are used to treat several medical conditions, namely many forms of anemia, especially aplastic anemia; acute and chronic wounds; renal failure (in combination with recombinant human erythropoietin); protein-calorie malnutrition with associated weight loss, such as HIV-associated wasting syndrome; and cancer-associated cachexia. AASs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, and their respective common dosages, are listed in Table 1.

Notwithstanding their benefits, the chronic use or abuse of AASs can cause several pathologic alterations, including hepatic, cardiovascular, reproductive, musculoskeletal, endocrine, renal, immunologic, and hematologic dysfunction, as well as psychological and psychiatric effects. Indeed, sudden cardiac death, suicide, and violent deaths have been reported to be more frequent than in the population in general in individuals with a history of long-term AAS use.8–16

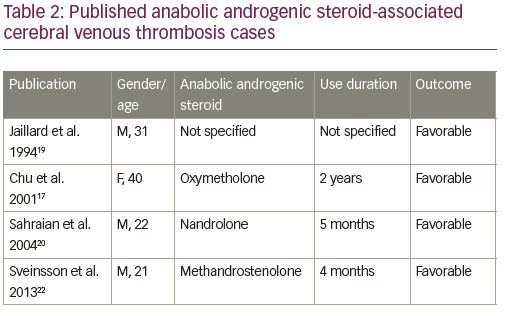

From the neurological point of view, some CVT cases have been reported in the last decade among AAS consumers, and there are probably many non-diagnosed cases due to the illegality of its use. AAS-associated CVT cases published until now are listed in Table 2, highlighting the type of AAS consumed, duration of use, and outcome of CVT.17–22 The exact mechanism by which AASs cause CVT is unknown; however, the existing evidence suggests that they promote fluctuations on the hemostatic system from an antithrombotic to a prothrombotic state. Additionally, in vitro experiences have shown that AASs can favor platelet agreggation.1–3,19

Despite the small number of published cases and the uncertainty about the exact mechanism by which AASs promote thrombosis, the fact that the patient had no medical relevant antecedents or risk factors, associated with the complete recovery after therapy, supports the conviction that high-dose and long-lasting AAS use should be considered a possible cause of CVT. Accordingly, it is very important to inquire about AAS use in cases of suspected CVT.

Minor post-publication correction: Compliance with ethics statement updated