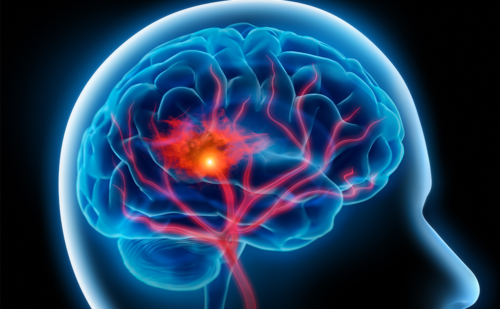

This delay in recognition of AD as a major neurological disease of aging does not reflect its impact.There are the personal tragedies that accompany the disease—the tragedy of having one’s memories, accumulated over a lifetime, gradually stripped away; the tragedy of watching someone you have loved and admired slowly losing their powers of thought, language, and often their personality; and the tragedy that comes with caregivers having to sacrifice to provide needed care, often at the expense of family disruption, financial loss, and depression. In addition, the economic cost to society is substantial; it has been estimated that close to US$100 billion is spent in the US per year in care and treatment of AD patients.

Due to the increased longevity of the US population, the absolute number of people afflicted by AD is expected to grow substantially.1 The US will see a 44% increase in the number of individuals with AD by 2025, affecting close to eight million Americans.Yet, given the demographics of the disease, if a treatment was developed that would push back the onset of the disease by only five years, the number of people with AD would be reduced by approximately half.

Of the current therapies for AD, most are based on the idea of neurotransmitter replacement. The most successful class of medications has been the cholinesterase inhibitors (tacrine, donepezil, rivistigmine, and galantamine). By enhancing cholinergic transmission, these drugs attempt to address the marked cholinergic deficits (up to 90%) seen in AD. The benefit of these medications is modest, but replicable across agents. On average, patients taking cholinesterase inhibitors (CEIs) may experience a transient improvement in cognitive performance measures, trending back to their baseline by six to 12 months.2 Similarly, differences between treated and untreated patients can also be seen on functional and behavioral scales. Due to the absence of multi-year placebo-controlled trials, the long-term effect of CEIs in AD is unclear. However, using data obtained from treated patients that have been followed in open label studies, there may be a sustained benefit lasting at least five years compared to historical controls.

Side effects of these medications are generally tolerable and include nausea, anorexia, and diarrhea. Often these bothersome cholinergic effects can be avoided by slow titration of the drug, or managed by concurrent use of peripheral anticholinergics such as glycopyralate or dicyclomine.

Some have questioned the cost-effectiveness of using CEIs. Many, but not all, pharmacoeconomic studies have found that this class of drugs is either cost neutral or actually results in cost savings, mostly by deferring placement in residential care or reducing caregiver time spent assisting patients.3 The place of CEIs in mild cognitive impairment is still unresolved. The term ‘mild cognitive impairment’ (MCI) is commonly applied to individuals that have memory deficits more than expected for age, relative preservation of other cognitive spheres, and no decline in day-to-day function. The majority of patients that fit the criteria for MCI have AD in an early stage. Studies of cholinesterase inhibitors in MCI have reported mixed results. One of the larger trials of donepezil versus vitamin E versus placebo only showed a reduction in progression to dementia in those on donepezil for the first 12 months of the three-year study.4

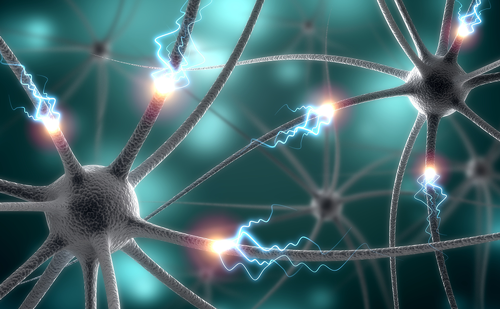

The other commonly used medication for AD is memantine. Glutamate is the principle excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain but may be abnormally regulated in AD. Memantine is an uncompetitive, low affinity N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-channel blocker that modulates glutamanergic transmission. Studies have shown that memantine can result in improvement in cognitive and behavioral spheres in those with moderate to severe AD.5 There have also been clinical trials of the combination of memantine and a CEI, suggesting a possible additive effect. Memantine is generally well-tolerated but may cause headache, dizziness, or confusion.

At this point in time, there is no evidence in humans to suggest that the effect of cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine are anything but symptomatic; that is, it is not yet known if they can in anyway protect against the underlying neuronal degeneration that occurs in AD. On the other hand, there is an abundance of research focused on discovering drugs that modify disease progression. There are over 100 clinical drug trials currently in progress or about to start in AD.

Many of these medications in development are designed to interfere with the production and deposition, or enhance clearance of, beta-amyloid, the protein felt by many to play a key role in the pathogenesis of the disease. A particularly intriguing approach has been utilizing immunotherapy techniques.6 A recent trial of a beta-amyloid vaccination in AD was cut short due to meningoencephalitic symptoms in 6% of patients, but a subset of patients showed a slower rate of cognitive decline. Several immunological strategies ranging from gamma globulin and other passive immunization protocols to safer vaccines are under development or testing.

In addition to novel medications being studied, there has been interest in the potential of drugs or supplements currently available for other indications to be used in AD.Already there has been a large trial of vitamin E in moderately severe AD, suggesting a dose of 2,000 international units (IU) per day may delay functional decline. Though no significant risk was recognized in the trial, subsequent reviews have questioned the safety of high-dose vitamin E. A variety of other agents including statin drugs, rosiglitazone, and Gingko biloba are presently in clinical testing.

A common challenge in clinical care of the AD patient is management of behavioral disturbances. Unfortunately, there is a paucity of well-designed studies to guide prescribing practices for specific behaviors. A recent trial of atypical antipsychotic medications for psychosis, aggression, or agitation in AD found that side effects from these drugs seemingly offset their efficacy.7

In the upcoming decades, and in the absence of a cure, practitioners that manage elderly individuals will increasingly face the task of treating AD. Currently, the physician has a handful of medications that provide modest symptomatic benefit with which to work. Hopefully, that therapeutic armamentarium will expand in the years ahead.