Q. A number of drugs in development for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) have failed phase III clinical trials. Why do you think this is?

There have been a number of high-profile phase III clinical trial failures recently, raising the question why are these efforts not showing more promise? So far, there does not seem to be a single answer to this question. Certainly, a number of these trials used drugs that targeted either decreasing amyloid protein production or targeting fibrillary amyloid plaques with antibodies to assist the immune system in removing constituent proteins. With regard to decreasing amyloid production, both β-secretase and gamma-secretase inhibitors have failed. Potential reasons are: (i) adverse effects of these medications; (ii) targeting the disease in too late of a disease stage where progression is not reversible and several other neurodegenerative processes will continue whether or not amyloid is present; (iii) inhibiting amyloid production may inhibit disease process in dominantly inherited mutation-associated patients where there is excess amyloid production, but the vast majority of Alzheimer's patients have late-onset sporadic or late-onset familial forms of the disease where the mechanisms are more related to amyloid clearance failure; (iv) it may be that the amyloid hypothesis is wrong.

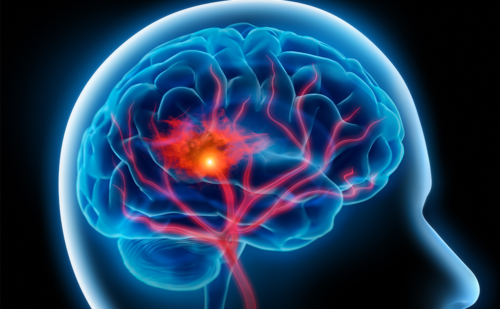

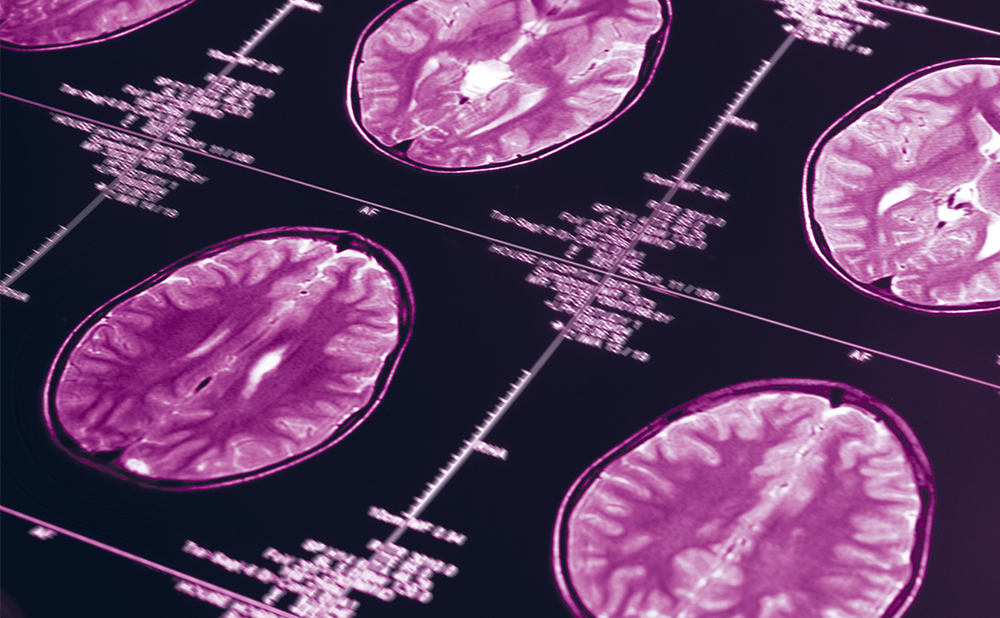

The other major approach is to use monoclonal antibodies targeting oligoclonal amyloid proteins and fibrillary proteins in plaques. A phase Ib aducanumab study has shown promise in patients with mild stage AD.1 The protocol used pushed antibody to relatively high doses and accepted a relatively high level of amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA). ARIA has since proven to be less clinically significant and more manageable as an adverse effect than originally thought. It was then determined that most other anti-amyloid antibody studies that had been enrolling patients were greatly under dosing levels of antibodies required to achieve amyloid plaque removal and potential clinical efficacy. Several trials have since been modified or new trials initiated using higher levels of antibody dosing. There also has been a move to target Alzheimer's patients at earlier mild cognitive impairment (MCI), or even earlier, amyloid positive on PET scan, but pre-symptomatic stages.

Q. What are the limitations of targeting amyloid-beta peptide (Aβ) in AD?

The major limitations of targeting Aβ are as follows:

(1) Too high a dose of antibody advanced too rapidly causes microhemorrhage and/or vasogenic edema.

(2) Mild or moderate stages of disease may be too late with damage already done with other ongoing disease mechanisms continuing.

(3) Drugs that inhibit amyloid production have had toxicities.

(4) Expensive to select patients with amyloid present at baseline or measure amyloid removal (assessment requires lumbar puncture or amyloid positron emission tomography [PET]).

(5) Very small percentage (typically <2%) of antibodies administered gets into the central nervous system limiting potential efficacy.

(6) There are many other newly recognized targets, dozens of potential mechanisms of action or therapeutic targets for investigational drugs, as a consequence of various genes recently discovered to cause Alzheimer's disease. The major effort is currently focused on anti-tau antibodies and/or drugs that interfere with tau metabolism and/or processing.

Q. What other therapeutic targets are being investigated in AD?

There is progressively more interest in microglia and various inflammatory-related pathways as major targets for future therapy of this illness.

Q. What agents in clinical development appear to be most promising?

The most promising agent currently publicly disclosed would be aducanumab. Other β-secretase inhibitors and anti-amyloid and/or anti-tau antibodies are still wait and see.