The novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 has caused a worldwide pandemic, and its impact on healthcare systems around the world is still being investigated. The potential effect of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on people living with dementia and the ability of COVID-19 to precipitate the risk of developing dementia are particular areas of concern. This article provides an overview of the current understanding of the impact of COVID-19 on dementia risk, mortality, diagnostics and prevalence. It also provides advice on how to protect vulnerable populations of people with dementia based on the available scientific data.

Older adults during coronavirus disease 2019

Older adults are among the populations most vulnerable to the COVID-19 due to their decreased immunity and increased risk of underlying medical conditions. Older adults have been hit disproportionately hard by the pandemic, with most deaths occurring among people aged 75 or older. Age is the single most important risk factor for both COVID-19 infection and mortality.1 Older adults have required hospitalization and intensive care due to COVID-19 more often than younger people.2 The underlying health conditions of geriatric patients, such as hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease, make them more susceptible to the virus.3–5 These conditions can also make recovery more difficult. Geriatric patients tend to suffer from long-term effects of the virus, such as fatigue, difficulty breathing, muscle weakness and cognitive impairment.6–8 Indirect effects of the pandemic, such as isolation and the disruption of normal routines, might also lead to depression and anxiety among older adults.9,10

Except for direct infection, people living with dementia are also vulnerable to the societal and conditional changes that might occur during a pandemic. Such changes may indirectly precipitate increased mortality among people living with dementia, for example, through decreased social interaction, decreased care and isolation. A recent meta-analysis of mortality among people living with dementia during the COVID-19 pandemic showed that they experienced increased mortality during pandemic conditions, even without being infected by COVID-19.11 The vulnerability of people living with dementia makes it difficult for stakeholders to accurately predict the impact of pandemic conditions.

Coronavirus disease 2019 and the ageing nervous system

The nervous system transforms with age, leading to a variety of physical and cognitive changes. As we age, our muscles become less flexible, and our reflexes slow down.12 Additionally, our sensory abilities, such as vision and hearing, begin to decline.13 Neurotransmission also begins to slow down, leading to difficulty in processing information, forming memories and making decisions.14–16 Previous pandemics have shown that infections might cause long–lasting neurological sequelae.17–19 No pandemic in modern times has been as widespread as the COVID-19 pandemic, which thus represents an unknown challenge for neurologists and neurogeriatricians going forward.

COVID-19 can have a profound effect on the nervous system. The virus can affect the brain, spinal cord and peripheral nervous system, causing a range of neurological symptoms.20 These symptoms may include confusion, memory loss, difficulty speaking, difficulty walking and blurred vision.21,22 In more severe cases, COVID-19 can cause encephalopathy resulting in seizures, coma and even death.23,24 In addition, the virus can cause the inflammation of the brain and spinal cord, which can lead to permanent neurological damage.25,26 COVID-19 can also cause neuropsychiatric symptoms such as depression, anxiety and insomnia.27,28 There is also evidence of autonomic nervous system influence, with postural orthostatic tachycardia being reported as a sequela of COVID-19 infection.29

Coronavirus disease 2019 and the risk of dementia

It is well known among geriatricians and neurologists that all infections in older adults, including COVID-19, may lead to an increased risk of cognitive impairment and subsequent dementia.30,31 These concerns have been raised in conjunction with the current pandemic, and many studies have reported an increased risk of cognitive impairment or dementia following COVID-19 infection.32–36 There are also studies suggesting that COVID-19 might increase the progression of dementia.37–39 This is due to the ability of the virus to attack the brain and central nervous system and to cause inflammation of the brain tissue.

COVID-19 is thought to cause neurological damage in two primary ways. First, the virus has been found to induce a cytokine storm, leading to the inflammation of the brain tissue and subsequent neuronal damage and impairing cognitive functioning.40,41 Neuroinflammation is a well-established component of dementia, and there is an almost linear relationship between neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration.42 Second, COVID-19 has been found to cause damage to the brain and central nervous system. The virus causes microvascular changes or damage to lung function resulting in impaired flow of oxygen to the brain with subsequent impaired cognitive function.43–46

COVID-19 has an additional risk dimension when it comes to Alzheimer‘s disease (AD), as COVID-19 has been shown to exacerbate the main pathological components of AD, such as beta-amyloid neurotoxicity and pathological tau accumulation.47–51 It has also been suggested that COVID-19 might impair amyloid processing and mimic cerebrospinal fluid and serum biomarkers of AD, with decreased amyloid beta loads even in cognitively typical patients.52,53 Patients with COVID-19 who experience neurological symptoms can exhibit biomarkers commonly used in the diagnosis of AD. GFAP and tau levels tend to rise in COVID-19 with neurological symptoms, at least during the acute phase, indicating axonal damage and astrocyte response.49,54

The most well–characterized genetic risk factor for AD, Apolipoprotein E (ApoE),55 has been shown to have a negative impact on both disease severity and progression in patients with COVID-19. Human and mouse studies indicated that ApoE facilitates severe COVID-19 disease and subsequent sequelae.56,57 Patients carrying the at-risk variants of ApoE could, therefore, be considered a particularly vulnerable population due to the increased risk not only of dementia but also of severe COVID-19 infection.

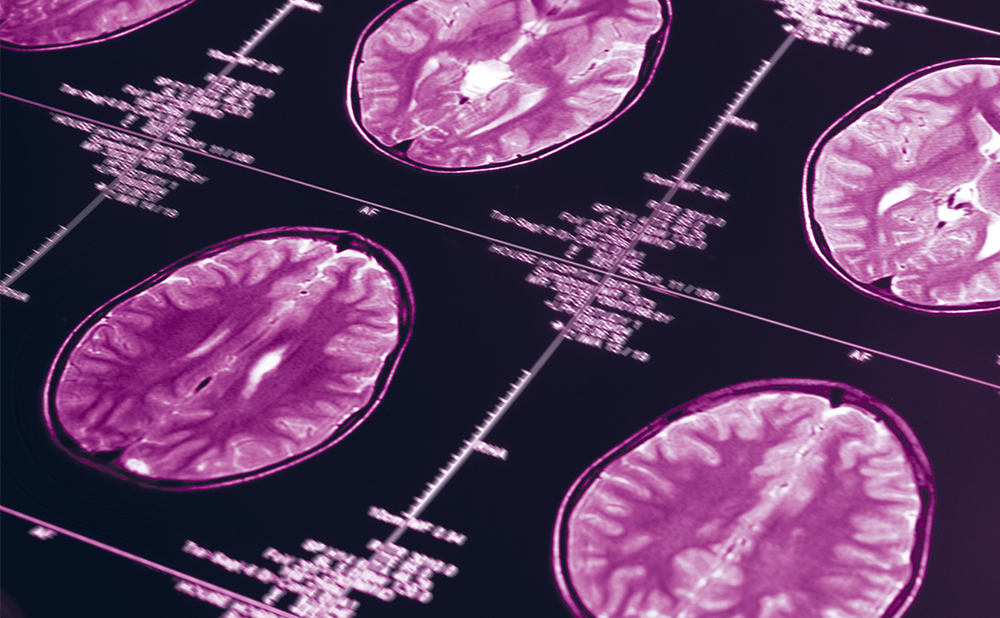

Neuroimaging data support the notion that COVID-19 causes detectable neurological atrophy, which might contribute to cognitive decline.58–60 In particular, damage to olfactory pathways, grey matter density, hippocampal size and orbitofrontal cortex has been noted.58–60 Although the significance of this change remains up for debate due to the lack of consistent terminology in the evaluation of COVID-19–induced pathology in neuroimaging and of long–term follow–up studies. The most likely outcome (i.e. that COVID-19 causes at least some permanent neurological damage) has to be evaluated in the coming years to detect any hallmarks of degenerative spread that could contribute to cognitive decline in survivors of COVID-19.

Electrophysiology is a common biomarker for AD, and it is easy to administer.61,62 Most of the literature attributes the neurological manifestations of COVID-19 to a parainfectious response rather than direct infection.63 This limits the useability of specific electrodiagnostic signatures to differentiate COVID-19 from other forms of neurophysiological abnormalities. Since neurophysiology is a relatively early biomarker for AD, clinicians should assess any potential confounding variables, such as previous COVID-19 infection, while evaluating dementia patients using electrophysiology.

Another way in which COVID-19 infections can lead to cognitive decline is by increasing cortisol levels.64 An increase in cortisol levels is known to lead to impairment of memory and other cognitive processes.65 The exposure would have to be chronic and sustained for cortisol levels to represent a significant risk factor. There is, however, currently no significant evidence of chronically elevated cortisol serum levels in patients after COVID-19 infections.

The pathological changes indicated by the biomarkers mentioned above might not result in a direct increase in symptomatology among patients with AD; however, it is not unreasonable to suspect that the increased brain pathology might speed up disease progression, representing a unique risk factor for post–COVID-19 infection in patients with AD.

Infections, such as those caused by COVID-19, can significantly impact cognitive functioning and lead to cognitive decline and dementia. This is most likely mediated through a series of potential mechanisms related to neurodegeneration and inflammation, as indicated by changes in various biomarkers. Several biomarkers specific to dementia are affected by COVID-19 infection and appear to be linked to both COVID-19 disease duration and severity;45–65 consequently, they represent a diagnostic challenge for physicians. If these changes in biomarkers response are temporary due to acute infection or the result of permanent damage remains to be seen; however, the progression of dementia symptoms post–COVID-19 infection indicate that irreversible neuronal damage is occurring. If so, cognitive impairment will then progress into dementia at increased rates during the coming years among parts of the population, adding to the strain on the healthcare systems. Indirect effects, such as stress brought on by pandemic conditions, should also be considered; these may, in turn promote dementia-related pathophysiology and neuroinflammation through stressor response. It is important to be aware of the potential risks of COVID-19 infection and to take steps to protect patients with dementia from further cognitive decline.

Currently, there is not enough research to conclusively confirm whether COVID-19 leads to dementia. However, it is not unreasonable to assume that COVID-19 causes long-term neurological damage, which might affect neurologically weakened individuals, such as older adults. Further research is needed to understand the full impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on neurological degeneration.

Clinical features and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 in people with dementia

People with dementia and COVID-19 often experience more severe symptoms and have a higher risk of severe disease and hospitalization compared with cognitively typical individuals.66–68 One of the most notable experiences of the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic were the reports of low prioritization of people with dementia in triage, partly due to the lack of standardized assessment protocols and the expected high mortality.69–71 The clinical treatment of people with dementia and COVID-19 is similar to the standard treatment for COVID-19, which includes oxygen supplementation, anticoagulants, anti-inflammatory medications and specific antiviral drugs.72 Patients with dementia are more prone to confusion and delirium due to their underlying condition, which can represent a clinical challenge. In particular, hypoactive delirium can be difficult to correctly identify for an inexperienced clinician due to the diagnosis relying entirely on clinical skills.73 Clinicians treating patients with dementia for COVID-19 should be well versed in the management of delirium and be aware of the detrimental effects of both the infection and the sudden changes in daily routines on people with dementia. Many medications for the management of delirium and confusion are readily available, but the proper use of these treatments often requires the consultation of clinicians with experience in treating patients with confusion, such as neurologists, psychiatrists or geriatricians. Clinicians working with patients with dementia infected with COVID-19 should implement a treatment–escalation plan and be in close contact with relevant consultants in order to react faster to the deterioration in the health condition of patients with dementia.

The diagnostics and prevalence of coronavirus disease 2019 and dementia

Correctly diagnosing dementia is important for identifying the underlying cause of the condition as well as providing symptomatic treatment and support.74–76 In particular, it is important because different causes of dementia require different treatments. For example, dementia with Lewy bodies is treated differently from vascular dementia.77,78 In addition, correctly diagnosing dementia is important for identifying any potential risk factors. Identifying the risk factors of dementia can help slow down disease progression and identify the best treatments for patients who already have the condition.79,80

It is likely that a significant portion of dementia cases have gone undiagnosed during the last 2 years, and a significant backlog of undiagnosed patients has likely developed. Reports of decreased dementia diagnosis rates have been reported by both researchers and patient advocacy groups.81–84 This decrease is likely due to the limited availability of healthcare, fewer doctors’ visits, social isolation and refocus of healthcare efforts during pandemic conditions.85–88 Dementia diagnostics is a complex procedure requiring specialist knowledge.89 There will most likely be an increase in patients requiring specialist assessment due to cognitive impairment and symptoms of dementia during the coming years, which will place a heavy burden on memory clinics worldwide.

Geriatric clinics and associations have not increased diagnostics and/or published recommendations and guidelines to promote greater awareness of this issue. This is worrying, as a correct dementia diagnostics is more important now than ever, with the recent approval by the US Food and Drug Administration of a disease–modifying treatment for AD, lecanemab.90,91 The lack of dementia diagnosis might result in a significant number of undiagnosed AD patients going untreated despite a disease-modifying treatment being available.

As discussed previously, the virus affects older adults through physiological and societal changes, such as social isolation and lack of physical activity, which may increase the risk of cognitive impairment or dementia. Additionally, the stress of the pandemic can lead to cognitive decline and make existing dementia worse. Furthermore, access to medical care has been more difficult during the pandemic. This leads to delays in dementia diagnosis and treatment that may worsen dementia symptoms.

In conclusion, because dementia was underdiagnosed during the COVID-19 pandemic, the prevalence of dementia is likely to increase during the coming years, and stakeholders should take steps to mitigate this.

Limiting the impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on people with dementia

Several strategies can be used to limit the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with dementia and people at risk of developing dementia.

Updated guidelines and protocols for memory clinics and primary care physicians for accurately assessing symptoms of cognitive impairment in patients post–COVID-19 infection need to be published. Clinicians should consider the uncertainty of the long-term influence of COVID-19 on common dementia biomarkers when evaluating dementia patients. Dementia has been underdiagnosed during the pandemic, and patients will slowly start to seek healthcare for memory problems as the pandemic regresses. Any increase in dementia populations will be detected in primary care, and efforts should be made to strengthen the first point of patient contact, for example, general practitioners in primary care, to facilitate a correct diagnosis.

On an individual level, caregivers should aim to reduce disruptions to daily activities that are effective at slowing down the deterioration of the symptoms of dementia. These activities include regular social interaction and exercise routines.92,93 Enabling a social and safe environment for people living with dementia can help prevent increases in stress, and in turn prevent adverse health outcomes.

On a societal level, the pandemic has negatively impacted healthcare accessibility.85,94 People with dementia are vulnerable, as they are often older and have more difficulty adapting to the most common methods developed during the pandemic to facilitate access to healthcare, such as online or remote consultations.95,96 To prevent this issue, stakeholders should aim to limit the impact on healthcare accessibility among older adults by facilitating access to healthcare, for example, through mobile teams or close communication between healthcare professionals and support staff at long–term care facilities. Other interventions could contribute to protecting vulnerable populations during pandemic conditions, such as enhancing public awareness of mental health, including dementia, providing adequate self-protection and avoiding environmental changes in long–term care facilities, such as reduced hours and fewer members of staff.

The proper management of dementia, such as by providing symptomatic treatment and adequate support and guidance for people living with dementia, should be prioritized in the post–pandemic world. This will minimize the effects of COVID-19 on adverse outcomes among people living with dementia.

Going forward, the epidemiology of dementia should be carefully monitored. Changes in dementia rates will provide valuable insight into the effects of the pandemic. Even though increased rates of dementia should be expected, decreased or stable rates of dementia diagnoses should be carefully evaluated as potential signs of overburdened healthcare systems.

Long-term cohorts should be established to study the effects of neurological sequelae after COVID-19 infections on people at risk of cognitive impairment and dementia. COVID-19 will likely influence the risk of developing memory problems, which will become more apparent as the world‘s ageing population increases during the coming decades. Dementia and cognitive impairment already represent a significant portion of healthcare spending.97 Even a small increase in dementia prevalence could cause serious disruptions to healthcare systems worldwide, in particular in industrialized countries where the ageing population is expected to increase significantly during the coming decades. Between 2015 and 2050, the proportion of the world’s population over 60 years is projected to nearly double from 12%–22%.98

Due to the high prevalence of COVID-19, with a significant portion of the world population having been infected at least once by 2023,99 particular focus should be directed towards tracking potential sequelae and their correlation with the biomarkers and symptoms of dementia. This objective could be achieved in several ways. The establishment of COVID-19 clinics with a focus on long–term sequelae could be beneficial for tracking any permanent damage caused by COVID-19 among larger patient cohorts. If COVID-19 causes permanent brain damage, which is not unlikely, then patients with memory problems should be carefully monitored to track the increased prevalence of cognitive impairment and/or dementia and to facilitate healthcare efforts.

Older adults, and those caring for them, should be made aware of the importance of social distancing, wearing masks and avoiding large gatherings during pandemic conditions. Avoiding infection is the most efficient way of avoiding the post–infection risk of cognitive impairment. Furthermore, the development of telemedicine and social interactions online might be a promising future area to limit the feelings of loneliness and anxiety among older adults during pandemic conditions. However, these efforts are dependent on accessibility accomodations in order to span the gap of limited digital literacy among older adults.100,101 Examples of these accommodations include screen readers, closed captions and text-to-speech devices.102 Other risk–reducing behaviours, such as a balanced diet and exercise, are also important.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has most likely impacted the future prevalence of cognitive impairment and dementia. This increase is due to multiple factors, including neurological damages caused by the virus, the effects of pandemic conditions on older adults and the catch-up effects of decreased dementia diagnosis during the pandemic. Overall, to reduce the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is essential to focus on dementia diagnosis and treatment. This includes providing access to regular medical care, mental health services and clinical trials. Additionally, it is important to provide support for caregivers, who might be overloaded by the added challenges of the pandemic. Future pandemic waves will most likely cause similar problems, and stakeholders can mitigate the impact through research, updated guidelines and greater awareness of memory–associated symptomatology among people after COVID-19 infection.