Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder and the most common form of dementia.1 It is characterized by two hallmark pathologies: the deposition of amyloid-β plaques and the neurofibrillary tangles of hyperphosphorylated tau.1 The clinical presentation of AD includes a progressive decline in two or more cognitive domains, which include memory, language, executive and visuospatial function, personality, and behaviour.1 These, in turn, can impair the ability to perform instrumental and/or basic activities of daily living.1

AD is a growing public health concern, which is predicted to affect 131 million people worldwide by 2050.2,3 The global cost of AD is also substantial and rising, up to an estimated US$2 trillion by 2030.2,3 As such, disease-modifying therapies in AD are urgently needed.2

Evolution of Alzheimer’s disease treatment

Cholinesterase inhibitors and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists

For many years, there have been only four approved medications to help improve cognition in patients with AD: the cholinesterase inhibitors donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine;4–6 and the NMDA receptor antagonist memantine.7 Cholinesterase inhibitors exert their therapeutic effect by increasing the concentration of acetylcholine at neurotransmitters through reversible inhibition of its hydrolysis by acetylcholinesterase.4–6 Memantine exerts its therapeutic effect via uncompetitive binding to the NMDA receptor, thereby attenuating the persistent NMDA receptor activation that is thought to contribute to AD symptomatology.7 While these treatments are effective in providing symptomatic relief for patients with AD, they are not disease-modifying treatments that can slow the progression of the disease.4–7

Therapies targeting amyloid-b and neurofibrillary tangles of hyperphosphorylated tau

Targeting the known pathological hallmarks of a disease is an established therapeutic strategy. Unfortunately, although there has been a great deal of research over past decades into AD treatments directed towards amyloid-β and neurofibrillary tangles, no clear advances have yet been made. Perhaps the most promising is the humanized monoclonal antibody aducanumab.8

Neuroinflammatory-directed therapies

Increasing evidence suggests that AD pathogenesis involves immunological mechanisms in the brain, with misfolded and aggregated proteins binding microglia and astrocytes.9 These trigger innate immune responses and the release of inflammatory mediators, thereby contributing to disease progression and severity.9 It seems increasingly likely that external factors, including systemic inflammation and obesity, can also interfere with the immunological processes of the brain and further promote disease progression.9 While there has been some evidence of a positive effect on cognitive decline in patients with AD receiving non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, these have not been replicated in later, larger trials.9 Nevertheless, it is important to diversify how we approach AD and its interventions, and the recognition that the immune system contributes to AD pathogenesis and offers potential routes for disease-modifying therapies.9

The role of the gut microbiome

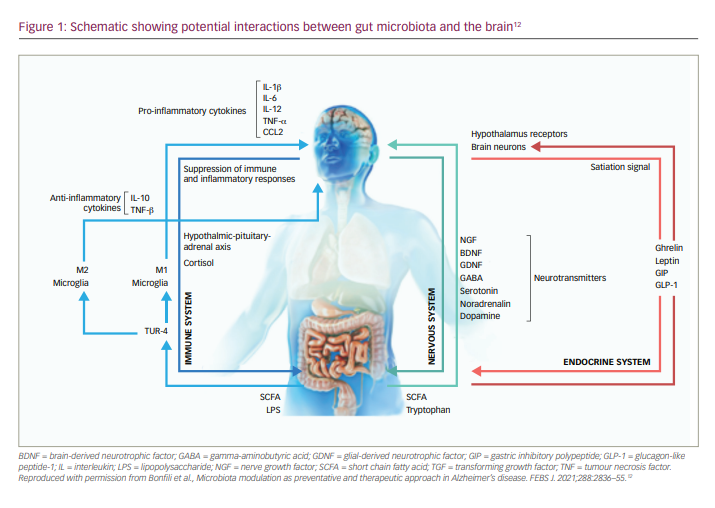

In recent years, the gut microbiome has increasingly become a focus of scientific investigation, and has been shown to play a key role in progressive neurodegenerative disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease.10,11 Central to this role is a dynamic interaction between the gut microbiota and the brain, termed the microbiota–gut–brain axis (Figure 1),11,12 which may contribute to both the ageing process and the trajectory of neurodegenerative disorders.10 This discovery led to research into the potential role of the microbiota–gut–brain axis in the pathogenesis and progression of AD, as well as the development of new therapeutic agents to target this mechanism and potentially slow the progression of the disease. There is now a growing body of evidence indicating a dysbiosis of gut microflora in patients with AD.12,13 Not only have studies shown that the gut microbiota is altered in patients with AD, but also that these differences may play a role in AD pathogenesis.14,15 Differences in gut genera have also been shown to be highly predictive of mild cognitive impairment, suggesting involvement at the very early stages of AD.16 Of potential therapies, multi-strain and mono-strain probiotic formulae have shown some efficacy in slowing cognitive decline in animal models of AD.11 Other potential therapeutic approaches aimed at modulating the gut microbiome include faecal microbiota transplantation, prebiotics, calorie restriction, digestion-resistant fibres and dietary supplementation.12

Recent developments

At the 13th and 14th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD) conferences in 2020/2021 (as well as the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference in 2021), there were many presentations of novel AD treatments related to amyloid-β, neuroinflammation and the gut microbiome. In one particular presentation by Professor Jeffrey Cummings, details of a planned global, phase III, multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 52-week trial (GREEN MEMORY [NCT04520412]) of the dietary compound sodium oligomannate (GV-971, Green Valley, Shanghai, China; 900 mg/day; capsule administration) in 2,046 patients with mild-to-moderate AD, were discussed.17,18 Sodium oligomannate is a marine-derived oligosaccharide that stimulates specific gut microbiota.19 The aim of the GREEN MEMORY study is to confirm the findings of a pivotal, phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 36-week clinical trial in 818 Chinese patients with mild-to-moderate AD conducted at 34 Chinese sites.19 In this study, patients with AD receiving oral sodium oligomannate (900 mg/day; capsule administration) showed a significant cognitive improvement compared with placebo after 36 weeks (mean modelled difference: -2.15 points on the 12-item Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS-cog12); p<0.0001; unadjusted difference: -2.54 points), with a similar incidence of treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs; 73.9% and 75.4%, respectively).19 Of the most common TRAEs, the incidence of hyperlipidaemia and nasopharyngitis appeared greater in the sodium oligomannate treatment group compared with the placebo group (7.1% versus 3.4% and 7.4% versus 5.6%, respectively); all other common TRAEs were similar between groups.19 The GREEN MEMORY study has now begun recruitment, with the first patient receiving their first treatment on February 3 2021. The study is expected to be completed in December 2025.18

The assessment of sodium oligomannate is of particular interest given the accelerated US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in June 2021 of aducanumab – the first potentially disease-modifying treatment for AD.20

Summary

For many years, only four approved pharmacological treatments have been available for people with AD: donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine and memantine. However, these only provide symptomatic relief. The accelerated approval of aducanumab, the GREEN MEMORY trial and information from the CTAD 2020 conference provide hope that new therapeutics with novel mechanisms of action may provide disease-modifying effects, and help slow disease progression in people with AD.