Dementia is a term used to describe acquired cognitive impairments that interfere with day-to-day functioning. In addition to describing a clinical syndrome, dementia also refers to the disorders that cause cognitive impairment.AD is the most common form of dementia, representing about two-thirds of all cases. Vascular dementia, dementia associated Parkinson s disease, and related disorders each represent about 10 20% of all dementias. Although different types of dementia have different clinical and pathological characteristics, it is not uncommon for multiple types of dementia to exist in the same individual.

Two pathological characteristics are observed in AD patients at autopsy extracellular plaques and intracellular tangles in areas of the brain essential for cognitive function. Plaques are formed mostly from the deposition of amyloid beta, a peptide derived from amyloid precursor protein (APP). Filamentous tangles are composed of neurofilament and hyperphosphorylated tau, a microtubule-associated protein.

There are two main risk factors for AD. The first and most important is age.The older a person is, the more likely they are to suffer from AD.The second risk factor is genetic predisposition. Specific disease-causing mutations in three different autosomal dominant genes presenilin 1, presenilin 2, and APP have been identified in association with familial, early-onset AD, which represents about 5% of all cases. For late-onset AD, one major susceptibility gene has so far been identified the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene. The APOE gene has different forms or polymorphic variants. Unlike the early-onset familial mutations, the E4 variant of the APOE gene is associated with a two to three times greater risk of developing AD, but having one or two copies of this form of the gene does not necessarily mean AD will occur.This illustrates the fundamental difference between a susceptibility gene with different variants and their attendant disease risk, and a specific mutant form of a gene that inevitably leads to a disease.

In the early stages of AD, specific aspects of memory are affected, namely short-term episodic memory.This may manifest as patients being able to remember what happened to them 20 years ago, but having difficulty remembering what they had for breakfast. A core clinical feature of AD is decreased ability to make new memories, i.e. learn new information, as opposed to recalling previously learned material. When episodic memory loss is the only clinical manifestation, it is referred to as mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Individuals with MCI have about a 50% risk of progressing to AD over a five-year period.

Early diagnosis leads to early intervention, yet with AD and other dementias early recognition is often problematic. If someone is in pain or is urinating more frequently, they seek medical advice sooner rather than later. Ironically, the very signs of early AD short-term memory loss, lack of concern or indifference, and impaired judgment often prevent an individual from appreciating the presence and significance of such symptoms and limit their ability to seek help. This makes it extremely helpful, almost essential, to have an informant available who knows the patient well for an evaluation.

The standard clinical practice of the diagnosis of AD has not changed significantly over recent years, and is based on taking a history of the cognitive behavior of the individual. However, there are some tests that could potentially become part of the standard diagnostic protocol of AD.

The ApoE4 test is already commercially available, but not widely used. Although it may be useful in specific situations, such as helping to confirm the diagnosis in a younger individual, it is currently not appropriate for routine clinical use.Diagnostic tests based on cerebrospinal fluid markers of beta-amyloid and tau are also available, but also not recommended for routine use at present. An increase in beta-amyloid levels and a decrease in tau levels are fairly accurate indicators for AD in a patient who has dementia. However, this test is not perfect, and may become more widely used in helping to predict whether an individual with MCI will go on to develop AD.

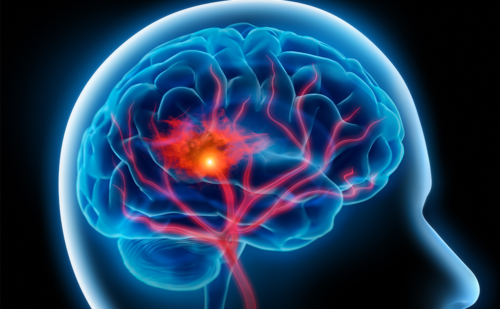

Structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans are currently most useful for ruling out non-AD dementias, such as vascular dementia, traumatic brain injury, and normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Research studies are currently under way to standardize measures of the earliest structural changes in the brains of AD patients, which is typically volume loss in the medial temporal lobe structures that subserve episodic memory. Newer MRI imaging techniques, such as diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), are being investigated as a possible means of identifying the loss of connections between brain cells in AD.

Although structural brain imaging is primarily used clinically to rule out AD, functional brain imaging offers the prospect of helping to confirm the diagnosis of AD and other dementias based on functional changes. In particular, positron emission tomography (PET) scanning using radioactivelylabeled glucose allows for the assessment of functional brain metabolic activity. In AD, metabolic activity is typically decreased in the medial temporal and parietal lobes, which is distinct from other dementias. Frontotemporal dementia (FTD), by contrast, is characterized by decreased brain metabolic activity in the frontal and anterior temporal lobes. PET brain imaging studies that assess patterns of metabolic activity are currently being reimbursed by Medicare in the US on a trial basis to help confirm the diagnosis of FTD. PET brain imaging studies such as these may gain more widespread acceptance in the differential diagnosis and pre-clinical detection of dementia. The greatest excitement in the field is reserved for amyloid PET imaging using the Pittsburgh-B compound. In these studies, the radioactive tracer injected into the patient shows how much amyloid has been deposited in the brain and where it is located, as opposed to showing metabolic activity as with standard PET imaging.

Although amyloid imaging studies are much more technically demanding and can only be done at major research centers in research studies, this technique may play a key role in detecting the earliest neuropathological changes in the brains of individuals who have yet to show any clinical symptoms of AD. Studies are currently under way to develop PET tracer agents that bind to amyloid like the Pittsburgh B compound, but would be applicable to more conventional PET imaging techniques that are widely available.

The current standard treatments for AD vary according to the severity of disease. Mild-to-moderate AD is treated with a class of drugs known as anticholinesterases, which increase the brain chemical acetylcholine. Examples include Aricept® (donepezil hydrochloride, Eisai/Pfizer), Exelon® (rivastigmine,Novartis), and Razadyne® (galantamine, Johnson & Johnson). Aricept® and Razadyne® are once-daily drugs, whereas Exelon® is dosed twice daily.The most common adverse effects of these drugs are nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Studies so far have shown that around 60–80% of sufferers have either slightly improved or stabilized over six months when taking these treatments.

There is only one approved drug for the treatment of moderate-to-severe AD—Namenda® (memantine, licensed by Forest Laboratories from Merz), an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist that decreases the level of another brain chemical thought to play a role in hastening brain cell death. A recent study suggested that combining drugs from these two main classes provides more benefit than either one alone. Although currently approved uses are specific to different stages of AD, it is likely that all drugs may benefit patients at any disease stage.

Both classes of drug are viewed to be symptomatic therapy. There has been no clear evidence from clinical data that suggests they alter the course of the underlying disease. However, pre-clinical data suggest that they might. Further studies to investigate the neuroprotective effects of variations of these treatments are on-going. A neuroprotective treatment would slow disease progression or prevent it in the first place even after the treatment is discontinued.

Currently, diagnosis of AD is triggered by the appearance of symptoms.The goal of researchers is to develop techniques that could diagnose people at risk before symptoms appear. This would then tie-in to new treatments for AD. Currently, there are no presymptomatic treatments for AD. Trials have been conducted with existing drugs such as Aricept®, and results suggested that the onset of AD could be delayed by up to one year, but the number of people who went on to develop AD did not change.

When it comes to new treatments under development for AD, the most exciting therapeutic prospects are anti-amyloid therapies.This includes the modulation of enzymes that breakdown the amyloid protein into less pathological forms, and long-term strategies that focus on the development of a vaccine. Vaccine programs targeting AD have shown some success in animals, but the one human trial that was conducted resulted in the death of some participants owing to autoimmune inflammatory processes in the brain. However, autopsies of these patients did show anti-amyloid effects, a case of winning the battle but losing the war.

The focus is now on improving safety through passive immunization, where antibodies raised against amyloids are injected into the body to bind to excess amyloid in the brain. Theoretically, this will not pose as much risk as active immunization, which resulted in the deaths in the earlier human trial. The vaccine approach to treat AD may have more promise than enzymatic modulation but is at an earlier stage of development.

Looking to the next three to five years, a number of new agents are in advanced clinical development and could see approval. Examples include:

” Alzhemed”! (Neurochem) designed to act on two levels, firstly to prevent and stop the formation and deposition of amyloid fibrils in the brain as well as to bind to soluble beta-amyloid, and secondly to inhibit the inflammatory response associated with amyloid build-up in AD.The drug is currently in phase III.

” Flurizan”! (R-flurbiprofen, Myriad Genetics) a selective amyloid beta 42 lowering agent that has been shown in cellular and animal studies to reduce levels of the toxic amyloid beta 42 peptide through the allosteric modulation of gamma-secretase. The drug is also currently in phase III.

” Leuprolide (Voyager Pharmaceuticals) this novel approach to treating AD has shown mixed results. It is based on the hypothesis that the condition is due to abnormal cell replication in the brain stimulated by increased gonadotropin levels in older adults who have lost reproductive function. Investigations are on-going as to whether, by lowering gonadotropin levels, a sustained-release implant of leuprolide (called Memryte) can have a positive impact on the disease.This is also in phase III.

” Xaliproden (SR 57746, Sanofi-Aventis) is designed to increase the production of neurotrophins such as nerve growth factor. ” Avandia (rosiglitazone, GlaxoSmithKline), which is used to treat diabetes, has been demonstrated to interfere with the degradation of beta-amyloid. Although there was no overall significant effect in a clinical trial, it showed benefit in a subgroup of AD patients that did not have the Apo E4 gene.

” Statin drugs, e.g. Lipitor® and Zocor®, are also being tested in large-scale clinical trials as potential neuroprotective agents to slow AD disease progression.

” CX 717 (Cortex Pharmaceuticals) is a glutamate alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor (AMPAR) modulator in phase II trials for MCI.

Alternative treatments such as ginkgo biloba have also shown some promise. While a 2002 study of healthy people who took over-the-counter ginkgo for six weeks reported no differences in memory or mental function, recent studies are reporting that a ginkgo biloba extract, called EGb 761,may slightly improve the memory of patients with mild-to-moderate AD.

The potential benefit of some of these drugs brings up an important issue. Data suggest that future treatments of AD may not adhere to a one-size-fitsall approach. We may have to look to personalized medicine to treat AD based on individual genetic characteristics. Investigations into new treatments and diagnostics of AD will likely converge at the level of the core pathologies in AD, but will also have to account for the heterogeneous and multifactor nature of the disease to be optimally successful.