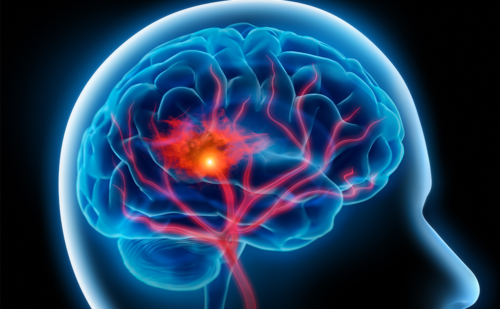

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the commonest cause of dementia. It is characterised by the presence of senile amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles and clinical characteristics consistent with gradual deterioration in memory function of at least six months duration together with other neuropsychological deficits, most typically aphasia, agnosia, apraxia and disturbance in executive function. Although, strictly speaking, AD cannot be diagnosed in the absence of clinical features, it is generally accepted that there is a preclinical phase that can be present for several years during which the underlying pathological features are progressing. Sometimes a further prodromal phase is defined, manifested as amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI)1. aMCI is a state where memory function is impaired at least 1.5 standard deviations below the mean, but where other cognitive domains remain relatively unaffected and where there is none or only minimal impairment of social function and activities of daily living (ADL). Once a person has entered the clinical phase of AD, non-memory cognitive domains are progressively involved together with deterioration in ADL. Figure 1 demonstrates this schema of AD progression.

A Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale2 has been devised to reflect this progression in both cognition and ADL. The CDR rating can take the value of zero for absence of dementia, 0.5 very mild, 1.0 mild, 2.0 moderate and 3.0 severe dementia.

In addition, progression to clinical AD may also be accompanied by behavioural changes. Such changes may occur at any phase and insome types of AD, such as that seen in adults with Down syndrome (DS), typically occurs at an early stage and may be an initial symptom.3 Moreover, some psychological or behavioural symptoms may pre-date clinical AD by several years and thus be considered as predictors of progression.

In this review, we will consider cognitive and behavioural predictors relevant to each stage of AD progression as represented in Figure 1.

To view the full article in PDF or eBook formats, please click on the icons above.