Pick complex refers to a spectrum of diseases with a variety of overlapping and pathological features. Although not ubiquitous, the presence of tau inclusions is a common feature in Pick complexes.1 The main neuropathological phenotypes comprise tau-frontotemporal lobar degeneration (tau-FTLD), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) and corticobasal degeneration (CBD).2 Although PSP and CBD were previously described as parkinsonian syndromes, cognitive disorders related to tau-FTLD are also observed clinically and pathologically.3 Extrapyramidal involvement in tau-FTLD has also been described,4 and there is considerable overlapping between these different diseases.5,6 PSP and CBD can have typical pathological features but there are also subtypes involving the cerebral cortex and basal ganglia.7 Tau-positive glial inclusions have been found in PSP and CBD, as well as in tau-FTLD.8

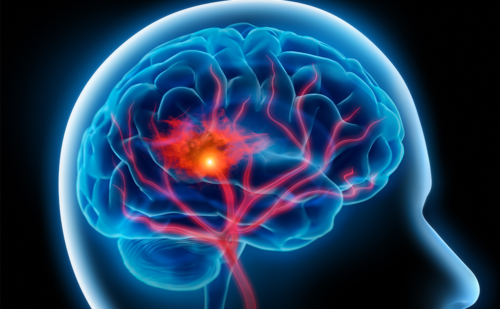

As there is considerable overlap between the subtypes of the Pick complex we wanted to evaluate the impact of small cerebrovascular lesions in these disease groups; it has already been observed that they are infrequent in frontotemporal lobar degeneration9 in contrast to their high incidence in Alzheimer’s disease10 and in Lewy body dementia.11

The present post-mortem study investigated the severity and the topographic distribution of small cerebrovascular lesions histologically and with 7.0-tesla magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in post-mortem brains of the various subtypes of the Pick complex compared with controls.

Material and methods

Seventy patients, who had been followed up at the Lille University Hospital underwent an autopsy and post-mortem MRI. This sample comprised 14 patients with tau-FTLD, 22 with PSP, 6 with CBD and 28 controls who had no history of brain disease. One fresh cerebral hemisphere was deeply frozen for biochemical examination. The remaining hemisphere, the brainstem and most of the cerebellum were fixed in formalin for 3 weeks.

Neuropathological examination

Diagnoses of tau-FTLD, PSP and CBD were made according to a standard procedure examining samples from the primary motor cortex, the associated frontal, temporal and parietal cortex, the primary and secondary visual cortex, the cingulate gyrus, the basal nucleus of Meynert, the amygdaloid body, the hippocampus, the basal ganglia, the mesencephalon, the pons, the medulla and the cerebellum. Slides from paraffin-embedded sections were stained with haematoxylin–eosin, luxol fast blue and Perl’s stain. In addition immune staining for tau protein, β-amyloid, α-synuclein, prion protein, TDP-43 and ubiquitin was performed.

A whole coronal section of a cerebral hemisphere at the level of the mammillary body was taken for the semi-quantitative evaluation of small cerebrovascular lesions such as white matter changes (WMCs), cortical microbleeds (CoMBs), and cortical microinfarcts (CoMIs). The mean values for WMCs ranking scores were: no change (R0), a few isolated WMCs (R1), frequent WMCs scattered in the corona radiata (R2) and WMCs forming confluent lesions of myelin and axonal loss (R3). For the other cerebrovascular lesions, their mean values corresponded to their percentage number.12

MRI examination

A 7.0-tesla MRI Bruker BioSpin SA was used with an issuer–receiver cylinder coil with an inner diameter of 72 mm (Ettlingen, Germany), according to a previously described method.13 Three coronal sections of a cerebral hemisphere were submitted to T2 and T2* MRI sequences: a frontal section, a central section and a section at the level of the parietal and occipital lobe. The brain sections, previously cleaned from formalin, were placed in a plastic box filled with salt-free water; the size of the box did not allow significant tissue movements.

The ranking scores of severity of the WMCs were evaluated separately in the different brain sections using the same method as the neuropathological section: no change (0), a few isolated WMCs (1), frequent WMCs scattered in the corona radiata (2) and WMCs forming confluent lesions (3). The number of small cerebrovascular lesions was also determined by consensus evaluation. The inter-rater reliability resulted in an interclass correlation coefficient of 0.82.

Statistical analyses

Comparisons between the three diseases and the normal controls were carried out separately. Univariate comparisons of unpaired groups were performed with Fisher’s exact test for categorical data. The non-parametric Mann-Whitney U–test was used to compare continuous variables. The two-tailed significance level was set at ≤0.01 for significant and at ≤0.001 for highly significant. Values set at ≤0.05 and >0.01 were considered marginally significant and were not classed as relevant due to the relatively small sample sizes.

Results

The average age at death was 67 (standard deviation [SD]: 13) years for the patients with tau-FTLD and 71 (SD: 5) years for the patients with CBD; neither were statistically different from the age at death for control subjects, which was 66 (SD: 9) years. On the other hand the patients with PSP with an average age of 74 (SD: 10) years were statistically older than the controls (p≤0.01). The gender distribution was similar in all groups with a male percentage of 64% in the controls, 38% in tau-FTLD, 55% in the PSP and 33% in the CBD brains.

Overall neuropathological examination showed a low incidence of cerebrovascular lesions in the control groups as well as in the Pick complex subgroups. Only WMCs were statistically increased in the tau-FTLD group (p≤0.01). CoMBs were increased in the tau-FTLD and CBD brains (p≤0.01) (Table 1).

On MRI examination, WMCs were most significantly increased in the frontal (p≤0.001) and the central (p≤0.01) sections of the tau-FTLD group. Also in the PSP and CBD groups, WMCs were statistically more frequent in the frontal sections (p≤0.01) (Figure 1). No topographic differences in CoMIs and CoMBs were observed between the different coronal sections of the control and the Pick complex subgroups (Table 2).

Discussion

All Pick complex subgroups showed a similarly low incidence and topographic distribution of the cerebrovascular lesions compared to the control group with the exception of WMCs in the frontal sections. As previously demonstrated the latter are particularly severe in FTLD and are considered as part of the neurodegenerative process rather than representing additional cerebrovascular disease.14 The increase of CoMBs occurs in the most affected inferior frontal and superior temporal gyri of FTLD brains.15 In PSP brains microbleeds mainly occur in the brainstem and the cerebellum, where the neurodegenerative process is also the most prominent.16 The present study showed a similar increase of CoMBs in the most affected regions of the brains with CBD.

Although tau inclusions are rare in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS),17 a favourable vascular risk profile is also observed.18–20 ALS is associated with FTLD in 15% of cases.21

An inverted region on chromosome 17 is linked to many Pick complex diseases.22 Also in FTLD-associated ALS and the sporadic cases of ALS a novel locus at 17q 11.2 is observed.23,24 However, the significance of these associations is difficult to explain. All Pick complex diseases and the sporadic cases of ALS share a novel locus on chromosome 17 and have a favourable vascular risk profile.