These three streams, which provided the impetus for the explosion of knowledge of the complexity of chronic pain and the role of psychosocial and behavioral factors along with physical ones in understanding and treating chronic pain patients, culminated in the creation of the first multidisciplinary pain treatment centers. Rehabilitation-oriented multidisciplinary pain centers (MPCs) exploded onto the healthcare scene between the 1970s and 1990s.The prototype MPC was founded by Bonica at the University of Washington; however, numerous variants evolved. Several features that capture the essence of these facilities, including the presence of a range of healthcare professionals (e.g., physicians of different specialties, physical therapists, psychologists), some emphasis on a biopsychosocial model in treatment planning, diverse healthcare professionals working as an integrated team, emphasis on rehabilitation and accompanying self-management and not cure, and emphasis on functional outcomes and not only decreases in pain.4

Since the development of rehabilitation-oriented MPCs there have been a large number of studies5 and meta-analyses 6–8 supporting the clinical and cost effectiveness of these integrated programs. Paradoxically, despite the fact that there are more published studies substantiating the effectiveness of MPCs than any other treatment for pain,4 these programs are becoming an endangered species. Contributing to the paradox is that given all the calls for evidence-based medicine and the buzz phrase— ‘pay for performance’—third-party payers are refusing to reimburse for treatment at MPCs or are trying to ‘carve’ parts out, potentially diluting the effectiveness. Part of the problem is associated with the fact that despite general descriptions there are no standards regarding what constitutes an MPC. So there are all types of solo practitioners promoting themselves as MPCs even when they consist of a single modality.The result is that third-party payers have little basis for judging whether a facility that labels itself as such is, in fact, a multidisciplinary center.

Another contributing factor to the decline, if not complete demise, of MPCs is the perception that these programs are expensive. After all, if multiple disciplines are involved, they all need to be paid and the amount of space required is larger than would be required for a solo practitioner. However, even the most advanced single modality treatments for pain—surgery, implantation of spinal cord stimulators and drug administration systems, neural blockade, and state-of- the art pharmaceutical treatments—are expensive, especially when the cost of maintenance and treatment for iatrogenic consequences are factored into the equation. Consideration of the cost factors involved for rehabilitation-oriented MPCs and the alternatives has led some to conclude that MPCs are substantially more cost-effective than surgery, implantable devices, and neuroagumentation procedures.5 This message has not been acknowledged by third-party payers.

The consequence of reimbursement issues is resulting in a return to the earliest treatments of chronic pain where a solo practitioner utilizes a preferred method drugs, surgery, electrical modalities, physical modalities, and so on. Examination of the literature on the effectiveness of these approaches is, however, disconcerting. For example: the most potent medications available reduce pain by only about 30 40%, in fewer than 50% of patients; based on observation of the effects of single pharmacological treatments, a number of commentators have advocated the use of multiple medications ( rational polypharmacy ) to treat patients with chronic pain. However, there has been a dearth of controlled clinical trials evaluating the effectiveness and potential adverse effects of using drugs in combination; a substantial proportion of patients who are exposed to spinal surgery continue to report considerable pain, functional impairment, and complications associated with the treatment; implantable devices are expensive, and even carefully selected patients may not be pain free and show only modest improvements in physical and emotional functioning; and the long-term benefits of any treatment for chronic pain are largely unknown due to the brief duration of clinical trials. The current pain management armamentarium relies heavily on the ancient one. Opioids, non-steroidals, surgery, thermal agents, and physical modalities continue to be the mainstay of pain management. What has changed has been the development of new routes of administration of pharmacological agents (e.g., pumps, topical agents), electrical current (spinal cord stimulators, transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS), electrical stimulation of acupuncture needles), and the development of newer pharmacological preparations (e.g., antidepressants, anticonvulsants).

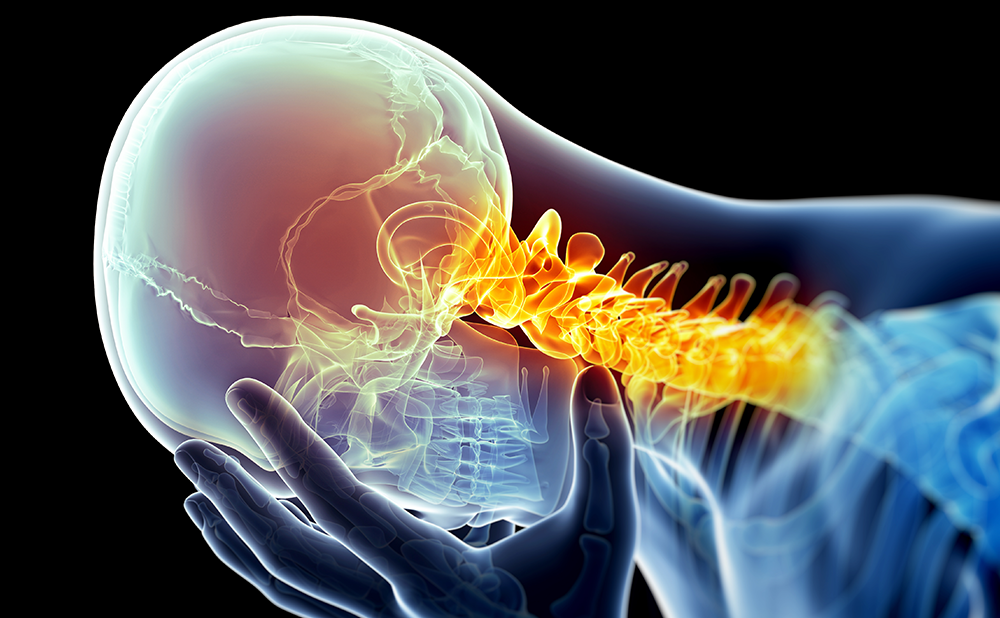

New Approaches in Neuralgia

Developments in medication coming on-line to treat neuropathic pain illustrate some of the advances in the clinicians treatment armamentarium. Neuropathic pain is now considered an integral part of chronic pain syndromes. It represents a variety of complex symptoms and is associated with a wide spectrum of disease states, including diabetes, cancer, stroke, spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis (MS), and post-herpetic and trigeminal neuralgia. Diabetes is one of the most common causes of neuropathic pain. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), of the estimated 18.2 million people with diabetes in the US, nearly 50% will have some form of neuropathy.

Treating neuropathic pain can be problematic, with few US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved options available. However, the use of off-label prescription drugs is common practice in pain treatment and particularly in the management of neuropathic pain. Treatment modalities have included: tricyclic antidepressants; selective serontinin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs); anticonvulsants; opioids; corticosteroids for cancer pain; anti-arrhythmics for neuropathic pain; and beta-blockers for migraine prophylaxis.

The successful use of off-label drugs has led to the development of specific treatment options. The firstgeneration anticonvulsant carbamazepine was the firstFDA-approved drug for trigeminal neuralgia. More recently, the second-generation anticonvulsant gabapentin was approved for post-herpetic neuralgia. This has been followed by FDA approvals for duloxetine (for diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain) and topiramate (for the prophylaxis of migraine in adults). Duloxetine belongs to a new class of antidepressants known as serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).Topiramate was first marketed as an anticonvulsant.

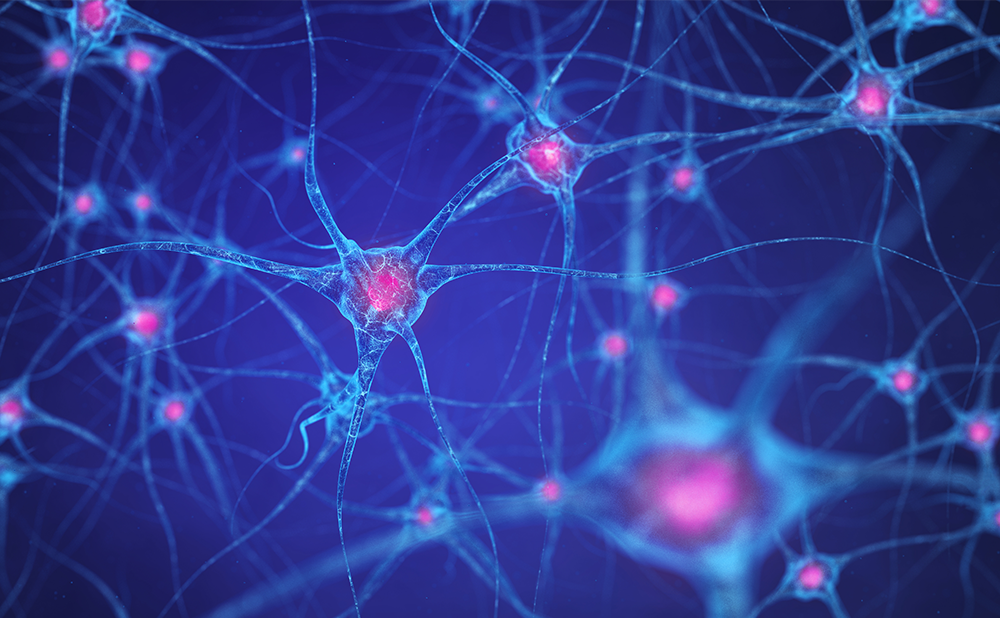

As the understanding of neuropathic pain mechanisms improves, so will opportunities for the treatment of chronic pain. Drugs under investigation include SNRIs for fibromyalgia syndrome, anticonvulsants for painful HIV-associated neuropathy, third-generation anticonvulsants for diabetic polyneuropathy, and cannabinoids.

What of the future, the decade of 2010 2020? As Niels Bohr acknowledged, Prediction is very difficult, especially about the future. But there are some areas where predictions can be made with some confidence. Advanced knowledge of neurophysiology, neuroanatomy, and neuroimaging will see the development of new classes of medications and more sophisticated surgical and other invasive approaches. Understanding of genetics will likely permit the customizing of treatment to individuals genetic codes. It is the authors belief that there will continue to be multidisciplinary teams involved in pain management. The composition, however, will be different to the past when they were made up exclusively of heathcare providers. The new multidisciplinary teams will consist of one or more healthcare providers along with an accountant. Coverage for psychosocial services will be an uphill battle despite evidence supporting their importance.