Overview of Fibromyalgia

FM is a common condition with an estimated prevalence of 2% of the general population (3.4% for women, 0.5% for men). Although all ages are affected, the prevalence increases with age, reaching greater than 7% in women aged 60 79 years. Given that the vast majority of FM patients are female, there is suspicion that gender-specific factors (e.g. ovarian steroids) may play a role in its development. In the US alone, FM is thought to affect as many as 10 million people, yet despite its prevalence, there are currently no medications indicated for the treatment of the disorder.

While the phenomenon of chronic widespread pain appears in the medical literature as early as the beginning of the last century, diagnostic criteria for classification and research purposes were not formalized until 1990, when the American College of Rheumatology published the consensus of a multicenter criteria committee. Accordingly, FM is classified by the presence of widespread pain in a symmetrical, primarily axial, distribution for a minimum of three months and the demonstration of tenderness to light palpation (4kg force) in at least 11 of 18 anatomically defined tender points. While the value of these criteria to the diagnosis and management of the disorder is the subject of enduring debate, they are the de facto diagnostic criteria in the clinical setting.

Besides the presence of chronic widespread pain, patients were also noted in the original classification document to commonly experience symptoms involving multiple bodily systems, including chronic fatigue and sleep disturbances, disturbed bowel function, genitourinary problems, and such allergic phenomena as persistent sinus congestion. A more recent document the Canadian Clinical Case Definition also places increased emphasis on neurological phenomena associated with the disorder, which include dysautonomia, nondermatomal paresthesias, headache, temporospatial dysmetria, restless legs syndrome, and cognitive dysfunction characterized by impaired concentration and shortterm memory consolidation, impaired speed of performance, inability to multi-task, and frequent cognitive overload.

Models of Fibromyalgia Pathology

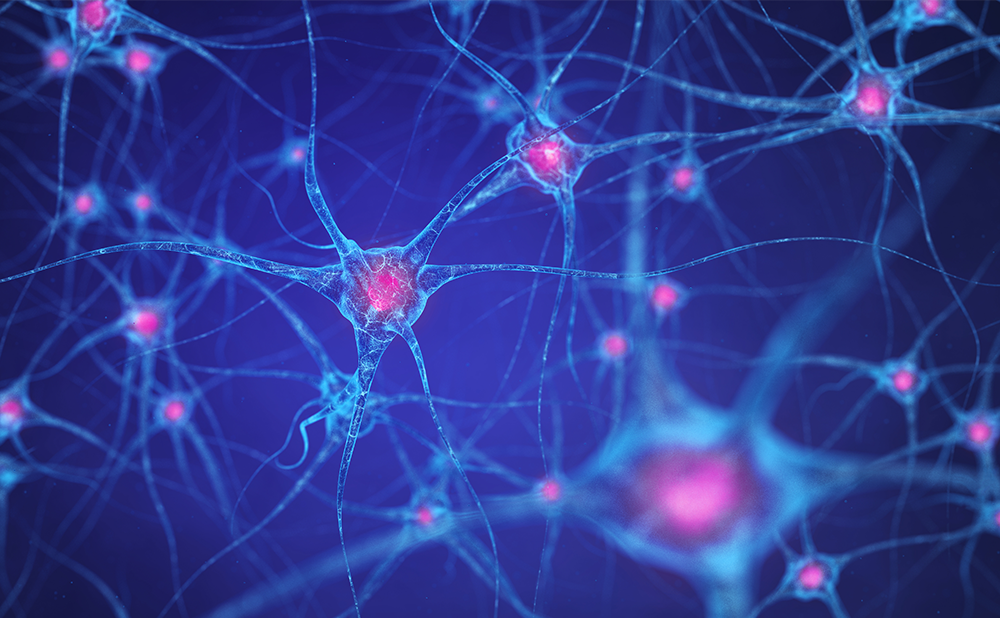

Among the obstacles to the development of effective treatments for FM is a persistent lack of understanding regarding the pathology underlying its chief symptom, i.e. chronic widespread pain. Broadly speaking, somatosensory perception may be conceptualized as involving three interrelated neurological processes: flow of afferent somatosensory information from the peripheral to the central nervous system; supraspinal processing of somatosensory information; and outflow of efferent signals via descending spinal tracts that modulates afferent drive by inhibiting or facilitating somatosensory input. A disruption of any one of these might ostensibly result in the subjective experience of increased pain.

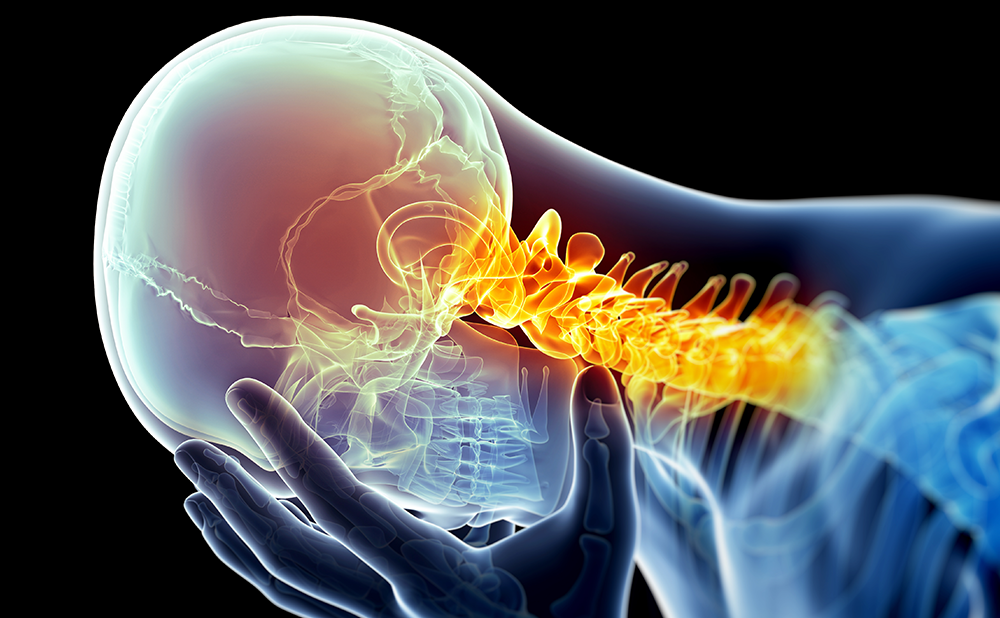

Peripheral sensitization of nociceptive neurons has been postulated as a potential mechanism underlying the pain of FM. For example, compromise of the vagus nerve, which produces a disruption of parasympathetic tone, results in an adrenergic-dependant reduction in pain thresholds. Intriguingly, autonomic imbalance characterized by sympathetic dominance has been demonstrated in FM, which has led to the proposition that FM pain may stem from disruption of normal autonomic function. Sensitization of the peripheralspinal interface (i.e. the dorsal root ganglia and spinal dorsal horn) secondary to increased activity of spinal n-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors has been demonstrated to result in the development of chronic pain. The suggestion has thus been raised that FM might likewise result from sensitization of central NMDA receptors. However, while initial experimental evidence appeared to support this hypothesis, subsequent re-evaluation of the experimental phenomena upon which the proposition was originally based appears to make it unlikely that sensitization of spinal NMDA receptors is the source of pain in FM.A failure of spinal descending inhibition represents another potential mechanism for the development of FM. Reversible disruption of spinal descending systems in animal models results in hyperactivity of spinal nociceptive neurons characterized by increased background activity, decreased threshold of stimulation, and an increased magnitude of response to noxious stimulation. A failure of descending inhibition in patients could ostensibly result from mechanical abnormalities in the foramen magnum or cervical spinal canal, or from a physiological failure of the neurotransmitters upon which these systems depend, i.e. endogenous opioids, serotonin, norepinephrine, or dopamine. Conversely, an increase in descending facilitation arising from dysfunction at the level of the peri-aqueductal gray or rostral ventromedial medulla might also result in the development of increased pain perception.

Subjective awareness of sensory experience is constituted by the flow of excitatory information from the spinal cord that is largely received in the thalamus and distributed for processing within parallel brain networks. While the majority of excitatory events are transacted by the amino acid glutamate, a vast array of neurohormonal factors modulates these events. Thus, an imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory factors could lead to generalized amplification of somatosensory data resulting in poly-modal sensitivity. For example, a failure of dopaminergic neurotransmission has been suggested to represent the primary pathology in FM, a proposition based on three critical observations: the development of FM is frequently associated with stressful events; the experience of chronic stress disrupts dopaminergic activity in the otherwise intact organism; and dopamine plays a fundamental role in pain inhibition in multiple brain regions, including the thalamus, basal ganglia, and the limbic cortex.

Experimental Findings

An unfortunately intransigent misconception among many clinicians is that FM patients essentially have nothing wrong with them, a position that stems from the frustrating lack of readily demonstrable pathology in the soft tissues or blood. In reality, research has demonstrated a variety of abnormalities in association with the disorder

Abnormal Sleep-related Brain Activity

The first objective findings associated with FM were reported in 1975 by Moldofsky et al., who described anomalous alpha wave activity (dubbed ‘alpha-delta’ sleep) on sleep electroencephalograms (EEG). Indeed, by consistently disrupting stage IV sleep in young, healthy subjects, Moldofsky was able to produce a significant increase in muscle tenderness similar to that experienced by FM patients, which resolved when subjects resumed normal sleep patterns. Other EEG sleep abnormalities have since been described in subgroups of FM patients.

Poly-modal Sensitivity

In addition to chronic widespread pain, patients demonstrate sensitivity to multiple modalities including pressure, heat, cold, electrical, and chemical stimulation. Experiments examining pain regulatory systems have also demonstrated a dysregulation of diffuse noxious inhibitory control, an exaggerated wind-up response to repeat stimulation, and the absence of exercise-induced analgesia.Together, these results point to dysregulation of the nociceptive system at the central level.

Neuroendocrine Disruption

Disrupted neuroendocrine function has been demonstrated in FM, characterized by mild hypocortisolemia, hyper-reactivity of pituitary adrenocorticotropin hormone release, and glucocorticoid feedback resistance. A progressive reduction of serum growth hormone levels has also been documented—at baseline in a minority of patients, while most demonstrate reduced secretion in response to exercise or pharmacological challenge. Other abnormalities include reduced melatonin secretion, reduced responsivity of thyrotropin and thyroid hormones to thyroid-releasing hormone, a mild elevation of prolactin levels and disinhibition of prolactin release in response to challenge, and hyposecretion of adrenal androgens. Hyperactivity of hypothalamic corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) has been postulated as an explanation for the neuroendocrine disturbances that have been described. Intriguingly, an increase in cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of CRH has recently been demonstrated, with a positive correlation between CRH concentrations and pain.Autonomic Dysfunction

Functional analysis of the autonomic nervous system in FM has demonstrated hyperactivity of the sympathetic nervous system at baseline with reduced sympathoadrenal reactivity in response to stress orthostatic challenge and mental stress. Patients demonstrate a decrease in heart rate variability (HRV), an index of sympathetic/parasympathetic balance that which is more pronounced at night. Given that decreased HRV is an indicator of sustained sympathetic hyperactivity and/or parasympathetic hypoactivity, these findings are especially intriguing in light of preclinical data that demonstrate compromised parasympathetic activity results in an adrenergicdependent hyperalgesia.

Cerebrospinal Fluid Abnormalities

Perhaps the most reproducible laboratory finding in patients with FM is an elevation in cerebrospinal fluid levels of substance P, a putative nociceptive neurotransmitter. As previously noted, elevated concentrations of CRH have also been reported, as have increased concentrations of nerve growth factor, endogenous opioids, and metabolites of excitatory amino acids. In addition, reduced concentrations of metabolites of multiple antinociceptive bioamines (i.e. serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine) have also been reported.

Brain Imaging Studies

Evidence of abnormal brain function has been provided via functional neuroimaging. Single positron emission computed tomography (SPECT) of FM patients has demonstrated baseline abnormalities in regional cerebral blood flow within elements of the cortex, thalamus, basal ganglia, and inferior pontine nucleus. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has demonstrated hyperactivation of the primary and secondary somatosensory, anterior cingulated, and insular cortices in response to noxious stimulation, with a relative hypoactivation within the thalamus and basal ganglia. Neural activation in response to nonpainful stimuli has also been reported in such pain-related areas as the prefrontal, supplemental motor, insular, and cingulate cortices. Finally, a recent evaluation of presynaptic dopamine function using positron emission tomography (PET) reported a reduction in presynaptic dopamine activity within the brain stem, thalamus, and multiple regions of the limbic cortex, wherein dopamine plays a putative role in pain modulation, in part by inhibition of excitatory neurotransmission.

Novel Pharmacotherapy A Rapidly Developing Enterprise

As previously noted, there are currently no medications approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of FM.Among the suggestions raised by a review of pathophysiological models is that increasing synaptic levels of antinociceptive bioamines may represent a viable therapeutic strategy in the management of FM.The question then becomes which one might be most appropriate for this purpose: serotonin, norepinephrine, or dopamine? A number of trials have evaluated the efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for the treatment of FM symptoms with limited results. In general, agents with higher specificity for serotonin are less successful than those with mixed serotonin/norepinephrine activity. If dopaminergic dysfunction plays a role in FM, then the propensity of serotonergic agents to disrupt dopaminergic activity might explain the failure of these agents to treat the core features of FM and, indeed, may represent a therapeutic liability.

A number of mixed serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are currently under evaluation for the treatment of the disorder, including milnacipran (Ixtel), duloxetine (Cymbalta), and desvenlafaxine (DVS-233). Of these, only duloxetine is currently available for use in the US. Other reuptake inhibitors with no serotonergic activity appear to warrant consideration for formal therapeutic trials, including reboxetine (Edronax), a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor approved of in Europe for the treatment of depression, and radafaxine (GW-353162), a stereoisomer of a bupropion metabolite that acts as a mixed norepinephrine/dopamine reuptake inhibitor.While serotonin is better known for its role in descending inhibition, it also plays a role in descending facilitation via a tract that originates within the rostral ventromedial medulla. Studies in Europe have demonstrated benefits in FM from treatment with tropisetron (Navoban), a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist that ostensibly blocks spinal descending facilitation.An alternative strategy for limiting pain-related neurotransmission is to inhibit the release of excitatory amino acids. Accordingly, controlled trials of pregabalin (Lyrica), which inhibits presynaptic glutamate release by binding the alpha-2-delta subunit of voltagedependent calcium channels, have shown promise in the treatment of the disorder.

The proposition that sympathetic hyperactivity may play a fundamental role in the development and expression of FM symptoms inspired the author of the current review to conduct a trial of pindolol (Visken), a mixed beta-1/beta-2 receptor antagonist, for the treatment of the disorder.While limitations of the study included an open-label design and limited subject enrollment, the results were encouraging enough to garner this agent a prominent role in the local management of the disorder.

Given the evidence for dopaminergic dysfunction in FM, it is perhaps not surprising that trials of dopamine agonists pramipexole (Mirapex) and ropinirole (Requip) have met with success in alleviating symptoms of the disorder. Controlled studies have also demonstrated significant benefit from treatment with sodium oxybate (Xyrem), a sodium salt of gammahydroxybutyrate with marked sedative properties. While the benefits of sodium oxybate have been largely attributed to its capacity to consolidate and improve deep sleep, it is intriguing to note that gamma-hydroxybutyrate also increases dopamine synthesis while simultaneously decreasing the threshold for burst firing of dopaminergic neurons, which is thought to be responsible for the analgesic capacity of dopaminergic neurotransmission.

Conclusion The Winds of Change

Despite recent advances in our understanding of the disorder, FM remains a controversial entity. This notwithstanding, objective evidence of demonstrable pathology within the central nervous system makes the unbeliever s position increasingly untenable. It is perhaps ironic that the writings of one of the fathers of modern neurology inspired a nearly century-long quest for pathology in the peripheral tissues. While FM has traditionally fallen under the therapeutic auspices of the rheumatology community, there is growing dissent among its rank and file regarding their role in its management. If the disorder indeed stems from abnormalities within the central nervous system, then neurology may anticipate being asked to play a more prominent role. The mounting evidence of dopaminergic dysfunction in FM invites comparison with another condition that involves a disruption in dopaminergic activity, i.e. Parkinson s disease, which is likewise associated with chronic fatigue, autonomic dysfunction, genito-urinary and gastro-intestinal disturbances, sleep-related abnormalities, frequent psychiatric involvement, and mysterious musculoskeletal pains. For those who would rise to the challenge, the observation is offered that both personal and professional satisfaction results from providing meaningful relief to patients afflicted by what remains one of medical science s enduring mysteries.