In the US, the incidence rate of new or recurrent stroke is approximately 795,000 per year, and stroke prevalence for individuals over the age of 20 years is estimated at seven million.1 Mortality rates in the first 30 days post-stroke have decreased owing to advances in emergency medicine and acute stroke care. There is also strong evidence that organised post-acute, inpatient stroke care delivered within the first four weeks by an interdisciplinary healthcare team results in an absolute reduction of deaths.2,3 Despite these achievements, 25–74 % of stroke survivors require some assistance or are fully dependent on caregivers for activities of daily living (ADLs).4,5 Thus, stroke continues to represent a leading cause of long-term disability and long-term care placement.

Despite the publication of the Agency for Healthcare Policy and Research (AHCPR) Guideline for Post-Stroke Rehabilitation in 1995,6 many healthcare providers are unaware not only of stroke survivors’potential for motor recovery, but also common secondary complications of stroke. Since this time, a number of clinical practice guidelines have attempted to educate interdisciplinary stroke rehabilitation teams about many of these issues. This article summarises the best available evidence-based recommendations for interdisciplinary management of the stroke survivor and caregivers. The recommendations emanate from the work of the US Departments of Veterans Affairs and Defense (VA/DoD),7 the American Heart Association (AHA) Councils on Stroke and Cardiovascular Nursing,8 the Canadian Stroke Strategy (CSS),9 the Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (SIGN)10 and the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE).11 The article is organised into the two major sections of unique characteristics of the guidelines and common clinical recommendations.

Unique Characteristics of the Guidelines

Each of the guidelines has its own methodology for developing its guideline. A set of researchable questions and associated key terms were developed within a number of focus areas. Inclusion criteria were developed for the literature search. The literature search resulted in a body of evidence that was critically reviewed for the strength of its findings. Each panel reviewed the body of evidence that addressed a particular question using an established method, formulated recommendations, and graded the evidence supporting each recommendation.

Department of Veterans Affairs and Defense Guideline

The VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Stroke Rehabilitation is divided into seven sections, including topics in rehabilitation in the acute phase, medical rehabilitation problems (e.g. bowel, bladder, stroke prevention), medical comorbidities (e.g. hypertension, cardiac, depression), impairments (e.g. motor, sensory, communication, cognitive), basic and instrumental ADL, the rehabilitation program (e.g. needs, setting, interventions, community re-entry), and discharge from the rehabilitation programme (e.g. medical follow-up). The guideline offers three algorithms for the assessment of inpatient rehabilitation, the re-assessment of inpatient rehabilitation, and the assessment for community services. The first algorithm provides a framework for the evaluation of impairments and activity limitations and participation restrictions, medical comorbidities, potential secondary complications, and triage of rehabilitation services.

The second algorithm assesses functional progress and whether the stroke survivor in inpatient rehabilitation still requires inpatient services. The final algorithm assesses the need and environment for community-based rehabilitation services. All of the algorithms include the stroke survivor and caregiver in education and decision-making that are central to the patient-centred process.

American Heart Association Council on Stroke and Cardiovascular Nursing Guideline

The AHA Councils on Stroke and Cardiovascular Nursing guideline divides up rehabilitation care using two classification schemes. First, the guideline considers rehabilitation care in inpatient and outpatient environments, in chronic care, and at end-of-life. Each of the environments is defined, and the services provided to the stroke survivor are described. Second, the guideline uses the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF)12 as an organisational framework to provide an overview of the interdisciplinary team approach to rehabilitation. The ICF model acknowledges that stroke recovery is a multifaceted process encompassing the interplay of the pathophysiologic processes directly related to the stroke and its associated comorbidities, the impact that stroke has on the stroke survivor, and contextual factors such as personal and environmental resources. As a result, the impact of stroke is described in terms of loss of body functions and structures; activity limitations that stroke survivors experience in basic and instrumental ADLs; and participation restrictions that stroke survivors encounter when re-establishing previous or developing new life roles and societal involvement. Personal factors may include internal attributes (e.g. gender, comorbidities, ethnocultural background), whereas environmental factors include external attributes (e.g. family support, social attitudes, architectural barriers, healthcare resources).

Canadian Stroke Strategy Guideline

The CSS guideline draws its evidence from the web-based Evidence-Based Review of Stroke Rehabilitation.13 Like the AHA guideline, the CSS guideline attempts to make recommendations based upon the environment in which stroke rehabilitation takes place. In addition, it organises guidance into sections on best practices, rationale, system implications, and performance measures. For example, the best practice for prophylaxis of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) states: “Patients at high risk of venous thromboembolism should be started on venous thromboembolism prophylaxis immediately…” While the rationale for DVT prophylaxis is obvious, the system implication suggests: “standardized evidence-based protocols for optimal inpatient care of all acute stroke patients, regardless of where they are treated in the healthcare facility…” The related performance measure is defined as the: “percentage of patients with stroke who experience complications (such as venous thromboembolism) during [their] inpatient stay…”

As a result, this recommendation scheme proposes potential solutions to operationalise and monitor guideline implementation. Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network Guideline The SIGN guideline also bases its recommendations on the WHO ICF classification scheme. It is divided into five sections: organisation of services; management and prevention strategies; transfer from hospital to home; roles of the multidisciplinary team; and provision of information. The section on transfer from hospital to home takes into account community re-entry issues, such as post-discharge support, driving, and follow-up by a primary care provider. The section on roles of the multidisciplinary team emphasises the need for collaboration and communication. The section on provision of information emphasises active education and counseling techniques that take into account the needs, values, and preferences of the stroke survivor and his caregivers. The section concludes with a list of Scottish stroke advocacy and caregiver websites.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Guideline

Finally, the NICE guideline is the oldest of the guidelines, having been issued in July, 2008. The guideline encompasses comprehensive stroke care, of which rehabilitation comprises two sections: recovery phase from impairments and limited activities; and long-term management after recovery. The recovery phase sections consist of 52 sub-sections that cover general topics, a number of specific treatments, common impairments seen after stroke, activity limitations and personal and environmental adaptations and equipment. The long-term management section discusses monitoring disability and episodes of further rehabilitation, long-term support and care at home, management in nursing homes and residential care, and caregiver support. Following these recommendations, the guideline organises recommendations that are pertinent to nurses, physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech-language pathologists, and nutritionists. The guideline is scheduled for updating in December, 2011.

Common Clinical Recommendations

According to the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Stroke Rehabilitation,7 the primary goal of rehabilitation is to prevent complications, minimise impairments, and maximise function. A number of key points influence the types of recommendations on which the guidelines are based:

• Early assessment and intervention is critical to optimise rehabilitation.

• Secondary prevention is fundamental for preventing stroke recurrence.

• Every candidate for rehabilitation should have access to an experienced and coordinated rehabilitation team in order to ensure optimal outcome.

• The patient and family and/or caregiver are essential members of the rehabilitation team.

• Standardised evaluations and valid assessment tools are essential to the development of a comprehensive treatment plan.

• Evidence-based interventions should be based on functional goals.

• Patient and family education improves informed decision-making, social adjustment, and maintenance of rehabilitation gains.

• The rehabilitation team should use community resources for community reintegration.

• Ongoing medical management of risk factors and comorbidities is essential to ensure survival.

Based upon this paradigm, a number of recommendations made by most or all of the guidelines are summarised. To simplify the recommendations from the different clinical practice guidelines, the recommendations and classification scheme described by the CSS guideline is used (see Table 1).9 The summary of recommendations can be seen in Table 2.

Conclusion

A number of well-organised clinical practice guidelines in stroke rehabilitation have been published over the past three years. They all are updated from previous editions, have established methods for collecting and rating the scientific evidence, have established techniques for reaching professional consensus, and have clear structure in stating and justifying each recommendation.

However, the publication of these updated guidelines emphasises a major shortcoming. Despite the advances in stroke rehabilitation since the publication of the AHCPR Guideline for Post-Stroke Rehabilitation in 1995, the reader should note that many of the recommendations still carry an evidence level C rather than an evidence level A. There are still many questions to be answered to improve the level of evidence in stroke rehabilitation. As researchers continue to answer many of these questions, stroke survivors will be able to benefit from proven tools that decrease impairments, increase activity limitations and participation restrictions, and ultimately improve quality of life.

Stroke Rehabilitation – An Overview of Existing Guidelines and Standards of Care

Abstract

Overview

Over seven million stroke survivors live in the US today. Despite the publication of the first post-stroke rehabilitation clinical practice guideline in 1995, many healthcare providers are unaware not only of stroke survivors’ potential for functional recovery, but also common secondary complications of stroke. This article summarises the best available evidence-based recommendations for the interdisciplinary management of stroke survivors and caregivers from five sources: two in the US, one in Canada, and two in the UK. Unique characteristics of each guideline are described, followed by a list of common clinical recommendations found in most, if not all, of the guidelines. Despite the advances in stroke rehabilitation over the past 16 years, much research still needs to be done to improve the level of evidence in stroke rehabilitation.

Keywords

Stroke, rehabilitation, practice guideline, standard of care, review, societies

Article

References

- Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al., On behalf of the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2011 update: a report from the American Heart Association, Circulation, 2011;123:e18–e209.

- Briggs DE, Felberg R, Malkooff M, et al., Should mild or moderate stroke patients be admitted to an intensive care unit?, Stroke, 2001;32:871–6.

- Evans A, Harraf F, Donaldson N, et al., Randomized controlled study of stroke unit care versus stroke team care in different stroke subtypes, Stroke, 2002;33:449–55.

- Anderson C, Linto J, Stewart-Wynne E, A population-based controlled study of the impact and burden of care giving for long-term stroke survivors, Stroke, 1995;26:843–9.

- Kalra L, Langhorne P, Facilitating recovery: evidence for organized stroke care, J Rehab Med, 2007;39:97–102.

- Gresham GE, Duncan PW, Stason WB, et al., Post-Stroke Rehabilitation. Clinical Practice Guideline, No. 16. Rockville, Md: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; May 1995, AHCPR Publication No. 95-0662. Available at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/ NBK16656/#A27307 (accessed April 16, 2011).

- The Management of Stroke Rehabilitation Working Group on behalf of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense, and The American Heart Association/American Stroke Association, VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Stroke Rehabilitation. Available at: www.healthquality.va.gov/Management_of_Stroke_ Rehabilitation.asp (accessed April 16, 2011).

- Miller E, Murray L, Richards L, et al., On behalf of the American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Nursing and the Stroke Council. A comprehensive overview of nursing and interdisciplinary rehabilitation care of the stroke patient, Stroke, 2010;41:2402–48. Available at: http://stroke.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/short/41/10/2402 (accessed April 16, 2011).

- Lindsay MP, Gubitz G, Bayley M, et al., Canadian Best Practice Recommendations for Stroke Care (Update 2010). On behalf of the Canadian Stroke Strategy Best Practices and Standards Writing Group. Ottawa, Ontario Canada: Canadian Stroke Network, 2010. Available at: www.strokebestpractices.ca/index.php/stroke-rehabilitation

(accessed April 16, 2011). - Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, Management of patients with stroke: Rehabilitation, prevention and management of complications, and discharge planning. A national clinical guideline, Edinburgh, Scotland: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2010. Available at: www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/118/index.html (accessed April 16, 2011).

- Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party, National clinical guideline for stroke, 3rd edition. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2008. Available at:

http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG68 (accessed April 16, 2011). - World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). 2008.

- Teasell R, Foley N, Salter K, et al., Evidence-based review of stroke rehabilitation executive summary (13th Edition). Available at: www.ebrsr.com (accessed April 16, 2011).

- Guyatt GH, Cook DJ, Jaeschke R, et al., Grades of recommendation for antithrombotic agents: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice

Guidelines (8th edition). [published erratum in Chest 2008;34:47], Chest, 2008;133(6 Suppl.):123S–31S. - Wolf SL, Winstein CJ, Miller JP, et al., Effect of constraintinduced movement therapy on upper extremity function 3 to 9 months after stroke. The EXCITE randomized clinical trial, JAMA, 2006;296(17):2095–104.

Article Information

Disclosure

Richard D Zorowitz participated in the American Heart Association article that is discussed in this article. He serves on advisory boards for Allergan, Inc., Medergy Medical, Victhom Human Bionics, NDI Medical, and SPR Therapeutics and is a Research Safety Monitor for Bioness, Inc. None of these activities result in conflicts of interest for this article.

Correspondence

Richard D Zorowitz, 4940 Eastern Avenue, AA Building, Room 1654, Baltimore, MD 21224-2735, US. E: rzorowi1@jhmi.edu

Received

2011-04-20T00:00:00

Further Resources

Trending Topic

The prevalence of unruptured intracranial aneurysms (IAs) is approximately 3% of the population, with incidence on the rise due to the increased utilization of neuro-imaging for diverse objectives.1,2 The average risk of rupture for unruptured IA is estimated to vary from 0.3% to exceeding 15% per 5 years.3 Ruptured IA is the primary aetiology of […]

Related Content in Stroke

What is the Stroke Action Plan for Europe? Stroke is one of the most enormous burdens to healthcare services.1 Despite our combined efforts, it affects more than one million people annually in Europe. Although we have abundant knowledge regarding stroke ...

Introduction The term 'stroke' is used to describe an adverse clinical state involving interference of blood circulation to the brain due to obstruction or rupture of blood vessels.1 Stroke was previously categorized into a cardiovascular disorder until the release of ...

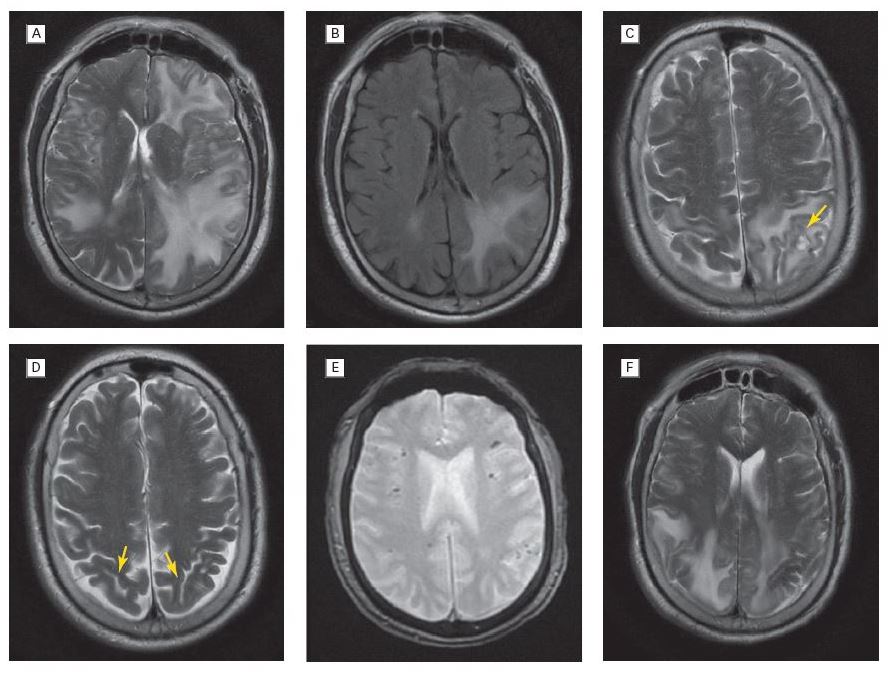

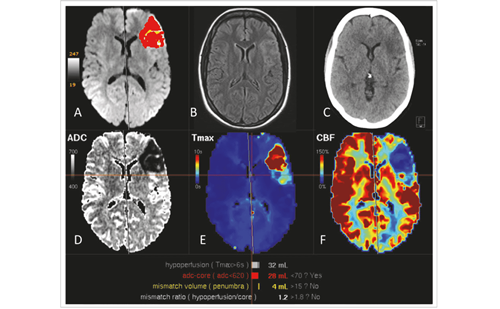

In clinical practice, the definition of penumbra is largely based on neuroimaging and indicates potentially salvageable tissue. Perfusion imaging has been useful in identifying this tissue when obeying ‘the mismatch concept’. The mismatch concept is a surrogate marker for salvageable ...

Ischaemic stroke may occur due to several potential mechanisms. Mechanisms are classically described as large artery atherosclerosis, small-vessel occlusion, cardioembolism, stroke of other determined aetiology (i.e. vasculitis, genetic disorder, etc.) and stroke of undetermined aetiology. Historically, the definition of ...

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), also known as congophilic angiopathy, is a recognized cause of lobar intracerebral haemorrhage in patients above the age of 50 years.1 It is known to be due to deposition of a variant of amyloid (beta-amyloid plaque) in ...

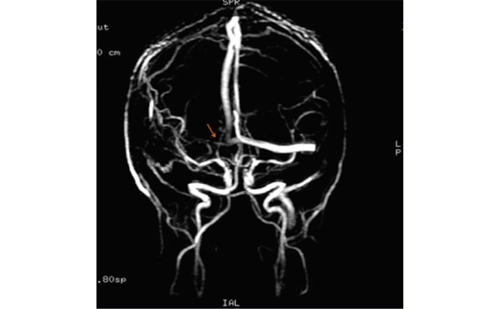

Cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) is a rare condition.1–3 While thrombophilias, contraceptive pill, hormonal replacement therapy, and neoplasms are well-established predisposing factors, steroid use is a less-common possible risk factor, particularly with regard to anabolic androgenic steroids (AAS).1–4 We intend to ...

Globally, a high proportion (around 25%) of transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) and ischemic strokes are cryptogenic.1,2 The Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) classification defines a cryptogenic stroke as a brain infarction that is not caused by definite cardioembolism, ...

In 2018, two randomised controlled trials, DAWN (the Clinical Mismatch in the Triage of Wake up and Late Presenting Strokes Undergoing Neurointervention with Trevo Thrombectomy Procedure) and DEFUSE 3 (Endovascular Therapy Following Imaging Evaluation for Ischaemic Stroke 3), implemented computed tomography (CT) and ...

Charles Bonnet syndrome (CBS) is characterised by the presence of visual hallucinations (VH) and visual sensory deprivation in individuals with preserved cognitive status and without a history of psychiatric illness.1 CBS is a rare, underdiagnosed and under-recognised syndrome, which was ...

About 85% of strokes are ischemic, and the most severe ischemic strokes are caused by large vessel occlusion due to either artery-to-artery embolism or cardiac embolism. Early treatment is essential to rescue potentially salvageable tissue.1 Until recently, the only proven ...

Welcome to the fall edition of US Neurology. This edition features a wide range of articles that provide an opportunity to review developments in the changing treatment landscape for neurological disorders and share expert opinions that should be of ...

Despite substantial evidence to the contrary, there is still a widespread belief that B vitamins to lower plasma total homocysteine (tHcy) do not prevent stroke. This belief is based on the failure of early clinical trials to show a reduction ...

Latest articles videos and clinical updates - straight to your inbox

Log into your Touch Account

Earn and track your CME credits on the go, save articles for later, and follow the latest congress coverage.

Register now for FREE Access

Register for free to hear about the latest expert-led education, peer-reviewed articles, conference highlights, and innovative CME activities.

Sign up with an Email

Or use a Social Account.

This Functionality is for

Members Only

Explore the latest in medical education and stay current in your field. Create a free account to track your learning.