Diabetes and ischaemic stroke are common conditions that often co-occur. The relationship between diabetes and stroke is bidirectional. On the one hand, people with diabetes have a more than two-fold increased risk of ischaemic stroke compared to people without diabetes.1 On the other hand, acute stroke can give rise to abnormalities in glucose metabolism, which in turn may affect outcome.2 In the current review, which is based on a recent paper from our group in the Lancet Neurology,3 we describe the management of diabetes both in the acute stage of stroke and in the longer term, with regard to secondary prevention.

Diabetes and the Risk of Stroke

A recent meta-analysis of prospective studies including 530,083 participants reported a hazard ratio for ischaemic stroke of 2.3 (95 % confidence interval [CI] 2.0–2.7) in people with versus people without diabetes.1 Considering that the estimated world-wide prevalence of diabetes in adults is around 10 %, this implies that one in eight to nine cases of stroke is attributable to diabetes.

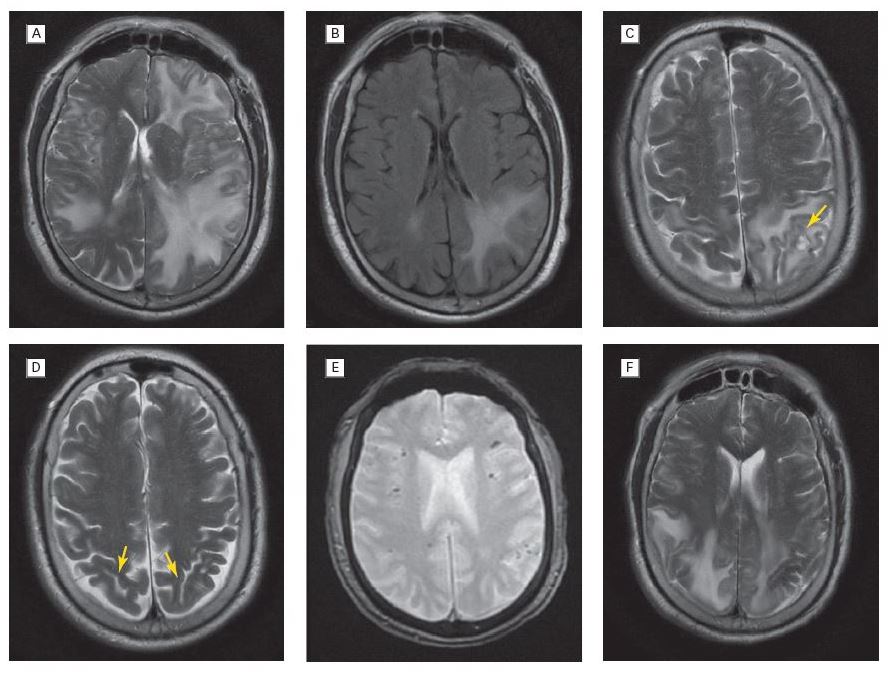

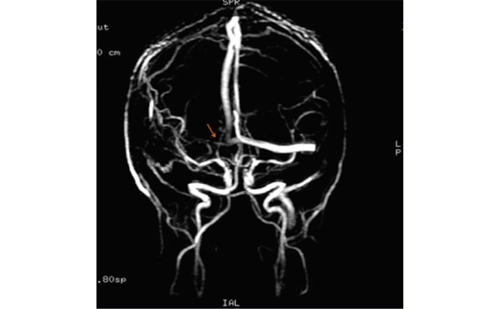

Diabetes is associated with different aetiological subtypes of ischaemic stroke, including lacunar and athero- and cardioembolic strokes.4–6 Moreover, the risk of atrial fibrillation, the major cause of thromboembolic stroke, is increased by 40 % in diabetes.7 Diabetes-associated risk factors for stroke include diabetes-specific factors (e.g. hyperglycaemia) and vascular risk factors (e.g. hypertension, dyslipidaemia), but also genetic, demographic, and lifestyle factors. The contribution of these factors, many of which are strongly interrelated, is likely to differ according to diabetes type and age.

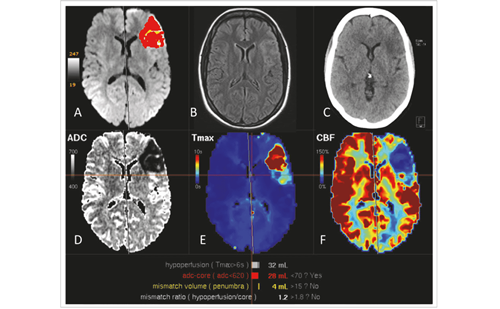

Hyperglycaemia and Stroke Outcome

Hyperglycaemia occurs in 30–40 % of patients with an acute ischaemic stroke.2,8 The majority of these patients does not have a known history of diabetes.2 In a proportion of patients hyperglycaemia reflects pre-existing but unrecognised diabetes, but more often it is due to an acute stress response, commonly named ‘stress hyperglycaemia’. Stress hyperglycaemia is defined as a fasting glucose >6.9 mmol/l or a random glucose >11.1 mmol/l during hospital stay that spontaneouslyreverts to normal range after discharge.9 Hence, glucose levels at admission generally do not distinguish between stress hyperglycaemia and diabetes. In this setting, elevated glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels (≥6.5 %) can help to identify previously undiagnosed diabetes.9,10

To view the full article in PDF or eBook formats, please click on the icons above.