About 20% of all brain infarcts are caused by atherothrombotic macroangiopathy.1,2 The prevalence of atherosclerotic carotid disease increases with age. Epidemiological data show a prevalence of 3.1% for men and 0.9% for women in individuals with ≥70% North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) criteria carotid stenosis who were 80 years or older. For ≥50% carotid stenosis, prevalence is 7.5% for men and 5.0% for women.3A pooled analysis of the general population indicates a prevalence of ≥70% carotid stenosis of 1.7% (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.7–3.9%).4 Due to improvements in medical therapy, the annual ipsilateral stroke risk of asymptomatic carotid stenosis ≥50% has decreased within the last decades from about 2% to 0.5–1.0%.5–7 Data are inconsistent as to whether the grade of stenosis (>70–99%) increases stroke risk.8–10 Risk of recurrent stroke in recently symptomatic carotid stenosis is reported with 6% in the first month and about 20% within the first year.11 Other data show a higher risk (21% in the first two weeks and 32% within 12 weeks).12More recent studies indicate a high risk (6–21%) of recurrent stroke in the first 72 hours after initial stroke symptoms, but a lower risk of 11.5% at 14 days, and 18.8% at 90 days.10,13,14 Quite low rates of recurrent stroke were seen under aggressive medical therapy with acetylsalicylic acid, clopidogrel and simvastatin (2.5% within 90 days).15Carotid atherosclerosis is also a marker for high risk of myocardial infarction and vascular death.16 Considering all these facts, patients with carotid stenosis should receive intensive medical therapy with statins and antiplatelets; treatment of hypertension and diabetes; they should follow a healthy diet, and perform lifestyle modifications.17–18

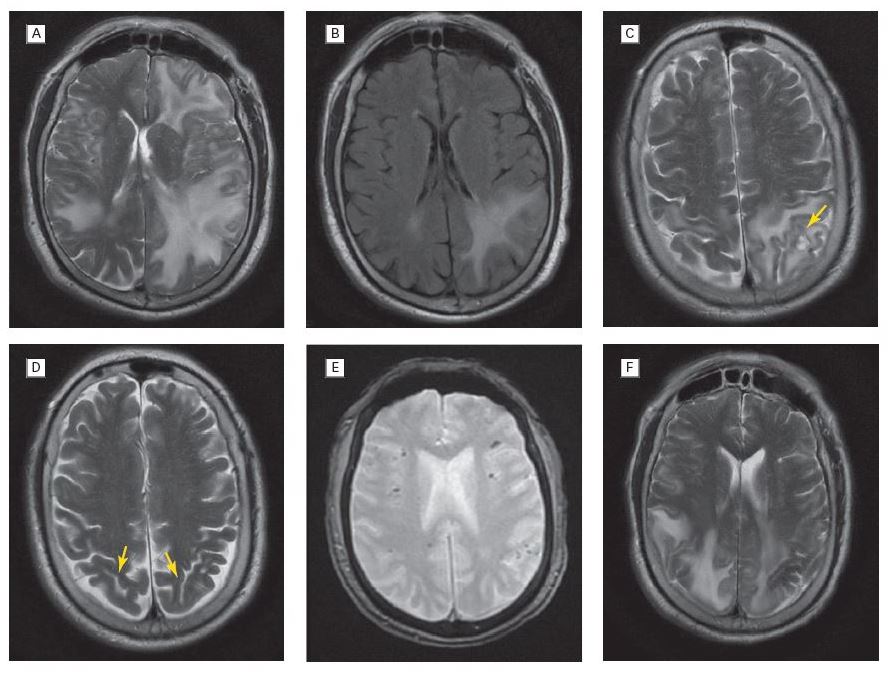

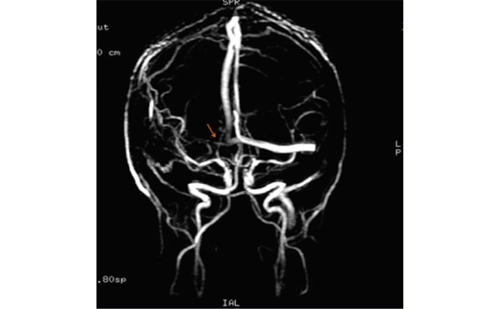

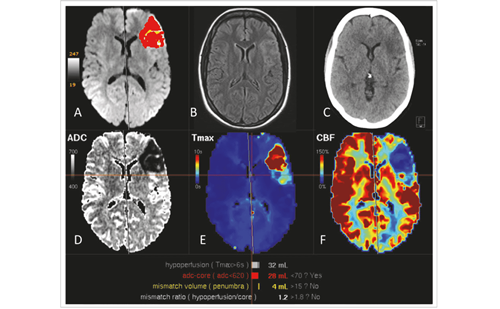

Discussions about invasive treatment of asymptomatic carotid stenosis are currently controversial. The recently published Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial-1 (ACT-1) study confirmed that carotid artery stenting (CAS) was non-inferior to carotid endarterectomy (CEA) in a cohort of 1,453 patients below 80 years of age with high-grade (70–99% lumen reduction) asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis.19 However, due to advances in preventative medicine, it is currently unclear whether any additional intervention by CEA or CAS actually has a beneficial effect. Interventional treatment may be justified in patients with progressive carotid stenosis and carotid embolism because of unstable plaque morphology, reduced cerebrovascular reserve, and the presence of silent embolic infarcts when risk of stroke or death induced by the intervention is ≤3%.4 A key issue here is to identify patients who are at a higher risk for ischaemic stroke using imaging techniques. Vulnerable plaques are one of the reasons for an increased stroke risk. Characteristics of vulnerable plaques as intraplaque haemorrhage, ruptured fibrous cap and lipid-rich necrotic core can be identified using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), intraplaque haemorrhage being the most well-studied parameter.20–21 A new protocol allows an accelerated acquisition time for the detection of intraplaque haemorrhage of five minutes, making it feasible for clinical routine.21 In addition, hypoperfusion caused by carotid stenosis can increase stroke risk and can be assessed by Doppler sonography, computed tomography (CT) or MR-perfusion and positron-emission tomography (PET).22–24

Burning questions, without recent evidence from randomised trials, are: whether CAS or CEA are still superior to a modern optimal medical therapy (OMT) in the primary prevention of ischaemic stroke in patients with a severe asymptomatic carotid stenosis; and whether CAS is at least non-inferior to CEA in terms of safety and efficacy. To gain data on this topic the investigator-initiated multicentre controlled randomised Stent-protected Angioplasty in Asymptomatic Carotid Artery Stenosis vs. Endarterectomy (SPACE-2) trial started recruiting in 2009. Unfortunately, after a study period of almost five years, the SPACE-2 trial had to be stopped due to low recruitment rates. Other trials exploring the best therapy in asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis are on-going: the Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial 2 (ACST-2) trial comparing CEA with CAS; the European Carotid Surgery Trial 2 (ECST-2) comparing CEA with OMT; and the Carotid Revascularization for Primary Prevention of Stroke (CREST-2) trial, which has a similar design to SPACE-2 study design (updated protocol).25–27A planned common database by the Carotid Stenosis Trialists Collaboration including all SPACE-2 data will be a platform for a combined analysis of all current randomised trials on asymptomatic carotid stenosis. This approach aims to give evidence-based answers to the optimal treatment of asymptomatic carotid disease. As medical treatment has led to a substantial decrease in stroke risk, most patients with carotid artery stenosis, especially when asymptomatic, should be treated with medical therapy only. If an intervention is planned, as many patients as possible should be treated within randomised trials.

Symptomatic carotid stenosis with acute neurological deficits within the previous six months, referable to this stenosis has to be treated more aggressively. If the grade of stenosis is ≥70% and not a near occlusion, treatment with CEA is evidence based and recommended in most guidelines if peri-interventional risk of stroke or death is ≤6% (level I, grade A). Moreover, patients with ≥50% stenosis and elevated stroke risk should be treated with CEA. CEA should be performed within two weeks of the last symptomatic event (level I, grade B). Alternatively, guidelines estimate CAS as a treatment option. In general, CAS carries a higher risk of embolic stroke whereas myocardial infarction is found more frequently in patients treated with CEA. CEA is recommended in older patients (>70 years), severe calcified stenosis or aortic arch, whereas CAS could be chosen in patients with distal carotid stenosis, cardiac comorbidity, radiation-induced stenosis, recurrent carotid stenosis after CEA, or contralateral paresis of recurrent laryngeal nerve.4,28–30CAS seems to be equal to CEA regarding long-term risk for ipsilateral stroke and myocardial infarction.31–32 In all cases, patient life expectancy should be at least five years, as the benefit of CEA/CAS emerges from one year after intervention.

Summary

Carotid stenosis has an increasing prevalence with age. CEA in recently symptomatic carotid stenosis ≥70% is an evidence-based therapy in secondary stroke prevention. CAS may be considered as alternative treatment in selected patient groups. Because of improved medical treatment effects, additional benefit of CEA or CAS of asymptomatic carotid stenosis is currently a controversial topic. Hopefully, on-going studies and pooled analyses of these trials will answer the question of how to treat patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis.