Migraine is the sixth most common form of disability globally that affects young, otherwise healthy subjects at the peak of their productive years.1 The management of chronic or refractory migraine with traditional pharmacological approaches can often prove challenging and unsatisfactory. In recent years, migraine therapy has witnessed rapid advance of techniques that offer a valid alternative to the common preventive treatments, with generally limited and tolerable side effects.

Noninvasive neuromodulation approaches act through the transcutaneous stimulation of either cortical areas or peripheral nerves that are involved in pain. They allow to extend a treatment previously reserved to a select subgroup of patients also to sufferers experiencing less severe forms of migraine, who nonetheless desire avoiding the common side effects caused by medication.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a noninvasive technique that was first discovered in 1985.2 It is applied externally to the scalp and creates a fluctuating magnetic field capable of inducing an electrical current to the underlying cerebral cortex, which in turn has the effect of changing the firing pattern of neurons. TMS has been shown to disrupt the wave of cortical spreading depression, which is thought to be the experimental correlate of migraine aura.3,4 CSD may indeed induce head pain via cortico-thalamic circuits.5 TMS has been used in a variety of research and clinical settings, including headache, mainly because of its safety and non-invasiveness.6,7 It can be delivered as one pulse or as trains of repeated stimulations; single-pulse TMS (sTMS) has been studied as a treatment for acute and prophylactic therapy in migraine, while fewer studies have evaluated the effect of repetitive TMS (rTMS).

A preliminary study using table-top sTMS device had shown good tolerability and efficacy in treating acute attacks in 42 migraine patients.8 A more feasible, hand-held sTMS device was tested in a randomised controlled trial (RCT) involving 164 migraine with aura patients.9 In this study, two TMS pulses separated by a 30-second interval were administered over the occipital cortex to treat a migraine with aura attack within one hour of symptom onset. TMS showed a 17% gain in pain-free rates at two hours with respect to the sham stimulation (39 vs. 22%). The effect was sustained at 24 and 48 hours. Given these positive results, a portable sTMS device has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration in the USA and Conformité Européen (CE) marked in Europe for the acute treatment of migraine with aura. A post-market pilot programme was performed in the UK to assess the impact of a three

month treatment with SpringTMS® (eNeura, US) on migraine patients with and without aura, both episodic and chronic.10 A total of 190 patients were involved, and the overall effect of sTMS was positive: there was a significant reduction of migraine days and attack duration, as well as a decrease in disability scores. No serious adverse events were reported. Furthermore, the study showed that the positive effect of TMS develops more the longer the treatment continues. A similar observational study is currently ongoing in the US and is aimed at evaluating the efficacy of sTMS in migraine with or without aura (NCT02357381). An RCT testing the use of rTMS over the visual cortex in preventing chronic migraine is also ongoing (NCT02122744). Limitations to the use of sTMS come from the observation that the main study exploring its efficacy was exclusively directed to aura patients; as in all device trials, it is also difficult to exclude a certain degree of unblinding although this was very well balanced in this study. The second study, although directed to a broader population of migraine patients, was not a RCT.

Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS)

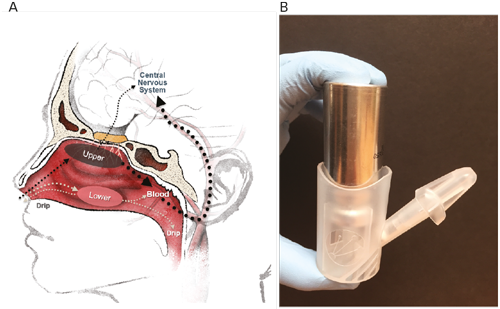

Invasive vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) was initially used as a treatment for epilepsy11 and depression;12 interestingly, its effect on headache was first suggested by observing a reduction in the frequency of migraine attacks – and not seizures – in a patient who was implanted with a VNS device for epilepsy;13 other preliminary reports further confirmed this result.14–16 The positive outcome of VNS on headache led to the development of a portable transcutaneous non-invasive device (GammaCore®; electroCore, US), which when administered on the neck stimulates the cervical portion of the vagus nerve by producing a mild electrical current then transmitted through the skin. The effect of transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS) has been studied in both the acute and preventive treatment of migraine, with generally mild and well-tolerated side effects such as skin redness, raspy voice and neck twitching.

The wide anatomical and physiological connections of the vagus nerve to major pain centres of the brain – with its afferents terminating in the trigeminal nucleus caudalis and dural nociceptive fibres being received by the nucleus tractus solitarius – may explain the effect of nVNS on headache, ultimately through a reduction of glutamate levels and neuronal firing in the spinal trigeminal nucleus17,18 and therefore by an ascending antinociceptive effect on the trigeminal nuclear complex.

An initial open-label single-arm pilot study investigated the use of nVNS in acute migraine attacks19 in 27 patients with episodic migraine. A total of 80 attacks were treated with two unilateral 90-second doses, separated by 15-minute intervals. Of the 54 moderate or severe attacks, 22% were completely aborted at two hours, while 43% had a significant reduction in pain scores. A further study gave similar results in 48 patients with high-frequency episodic and chronic migraine, confirming the positive effect of nVNS as an acute treatment.20 The use of nVNS in prevention of migraine has also shown promising results. The recent report from the EVENT study, a double-blind, sham-controlled pilot study in chronic migraine, showed that treatment with two 90-second doses administered three times a day caused a reduction of approximately two headache days per month in the treatment group, compared to no change in the sham group. This reduction reached almost nine days after the six-month open-label phase, compared to 5.5 in those initially assigned to sham, suggesting that long-term prophylaxis might be needed.21 Another open-label report on patients with episodic and chronic migraine showed an overall reduction of almost six headache days per month after a three-month nVNS preventive treatment.22 A randomised sham-controlled study for episodic migraine prevention is currently ongoing (NCT02378844). Future trials to confirm these results are warranted, given that the studies treated relatively small numbers of patients and that the double-blind phase for the only available RCT showed a somewhat modest reduction in headache days.

Transcutaneous supraorbital nerve stimulation

The use of transcutaneous electrical current administered to cutaneous sensory or cranial nerves for the treatment of headache has been applied for many years, and reappeared in the modern literature as long as 30 years ago,23 although its use has been limited because of conflicting results.

A novel technique based on the application of electrical current to the supraorbital nerve has recently been studied for migraine prevention in a randomised controlled trial.24 This RCT tested the use of a supraorbital transcutaneous stimulator called the Cefaly® device, applied bilaterally for 20 minutes daily for three months to the supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves, in 67 migraine patients. The treatment group showed a significant reduction in headache days, migraine attacks and use of abortive medications in respect to the sham group. Subsequently, a large survey was performed on 2,313 patients using the device, showing only minor adverse events and an overall high safety and satisfaction with treatment.25 Pitfalls in the study include unblinding caused by paresthesias induced by the device, which are quite noticeable and uncomfortable, as well as a relatively small improvement measured in terms of number of headache days. In 2014, the FDA gave nonetheless approval for the use of Cefaly device in the prevention of migraine, and the device is also CE-marked in Europe.

Conclusions

Noninvasive neuromodulation is an exciting and useful method that is being increasingly recognised as a valid strategy for migraine management. It not only offers a safe and effective alternative to pharmacological treatments, but also provides interesting insights into the biology of migraine itself. Further RCTs need to be undertaken in the future, however, to confirm these promising results.