In modern medicine, the concept of wellness is accompanied by many misconceptions. Adopting wellness as a treatment approach has been well defined and implemented in cardiovascular disease, diabetes and some types of cancer management but has not yet been widely applied to neurologic diseases.1–5 The commercialization of the wellness industry has led to the misconception of wellness as expensive and only accessible to a niche population who can afford gym memberships, massages, personal chefs and spa retreats.6 Hence, it is important to define wellness clearly. Wellness includes both preventative and holistic features and can best be defined as “the active pursuit of activities, choices and lifestyles that lead to a state of holistic health”.7 Wellness is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “the optimal state of health for individual and groups”.8 It represents a strengths-based approach to health, which focuses on a person’s positive attributes, a contrast to the traditional medical paradigm, which focuses on symptom mitigation.7

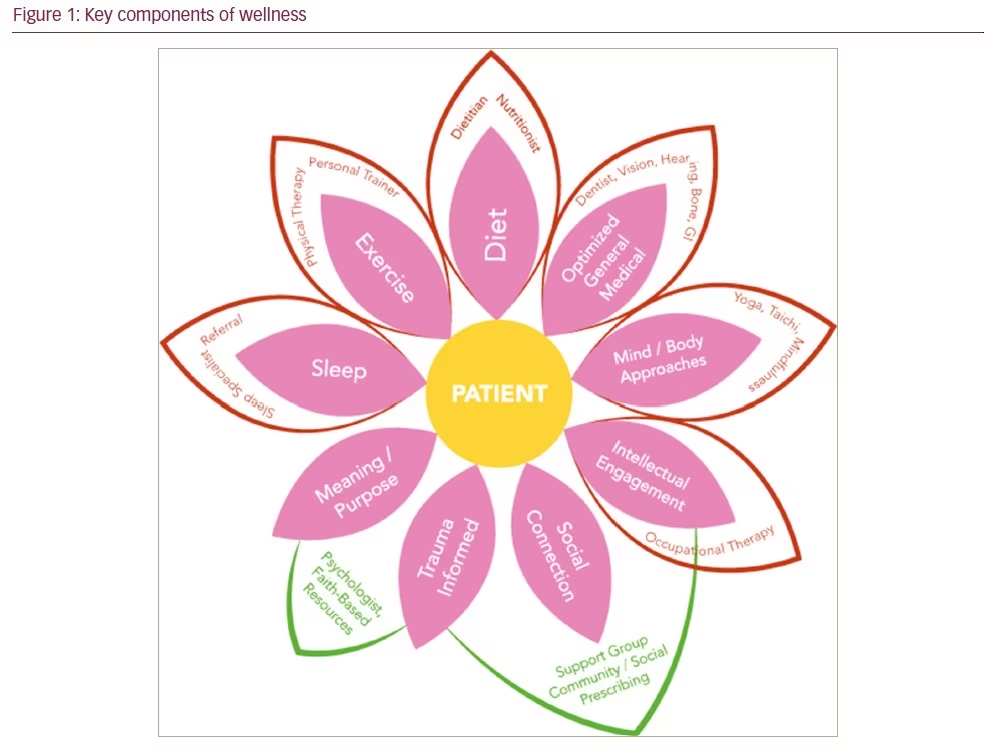

The WHO defined health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”.9 Wellness includes being engaged in attitudes that enhance the quality of life and maximize personal potential; hence, the wellness model fits well with this broader WHO definition of health. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health was established to provide a comprehensive system for conceptualizing health in a holistic manner by considering the interplay between the psychological, biological and social components of one’s ability to function optimally.10 The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health model encourages clinicians to both inquire about and consider the viewpoint of the individual patient regarding their health and wellness. Specific models of holistic health have been recently popularized, including the Veteran’s Affairs Whole Health model.11 This model of wellness is a multidimensional patient-driven approach to health encompassing lifestyle, environment, social support and spiritual, mental, and physical wellbeing. For people with Parkinson’s disease (PWP), the key components of wellness are a healthy diet, exercise, sleep, mind–body approaches and social connection.12–15 Figure 1 illustrates these key components of wellness, including the many referrals and collaborations that can enhance care for PWP.16 This figure is an updated version of the “The patient is the sun” figure by Bloem et al.17 We propose “the active pursuit of more holistic health through individual lifestyle choices and not just the absence of disease” framework as a revised approach to health provision for PWP.7

Historically, Parkinson’s disease (PD) was thought to affect motor function, with studies and care largely focused on older Caucasian men. However, it has now been recognized that PD is a complex disorder with multifaceted presentations, including motor and non–motor subtypes with a prodromal period (i.e. before patients meet current diagnostic criteria) of a decade or more.18,19 PD diagnoses are likely to increase dramatically over the next 20–30 years, prompting some authors to suggest that PD is an epidemic.20 Currently, treatment is focused on symptomatic therapies, primarily for physical symptoms, using medications or devices that are tremendously beneficial in restoring motor function and allowing patients to function in daily life.21 However, even with the best current therapies and wellness approaches, patients continue to experience symptom progression and mounting disease burden over decades. It has been proposed that there should be an emphasis on early assessment to allow for effective psychosocial management from the point of diagnosis through to palliative care.22–24

While disease modification is still aspirational, there may even be a role for wellness in counselling patients at risk for developing PD as predicted by genetic testing or in the prodromal phase of PD.25 There have been similar proposals for other neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease.26 Wellness–focused counselling that incorporates motor, non-motor and mental health offerings delivered in a personalized manner that is based on a bespoke dashboard of symptoms related to the PWP as a whole has been proposed. This approach builds upon the ‘dashboard vitals of PD‘, which include comorbidities/polypharmacy and dental, vision, bone and gut health, which go beyond just motor and non-motor issues in PD.27

In the traditional medical paradigm, the patient is often a passive recipient of care, and healthcare interventions are sporadic and often in reaction to a symptom or complaint rather than proactive or preventative. This intermittent interaction with the healthcare system is compartmentalized and remains separate from the patient’s day–to–day life. Patients often see their neurologist for only one 15–30-minute appointment every 6 months. In contrast, the wellness model places the patient at the centre of the care team, with goals defined in accordance with what they consider meaningful for their quality of life in their current social, economic and cultural context. The patient is responsible for making choices in their daily life (with individualized recommendations from their healthcare team) that influence their health outcomes, which cultivates self-agency (a feeling of control over actions and their consequences). This wellness pathway may allow the patient to thrive, going beyond the traditional mitigation of individual symptoms and complaints. Lifestyle choices and actions are integrated into daily life and are not just intermittent; thus, seeking health becomes a continuous pursuit.

Cultural and diversity considerations in wellness

Cultural competence is defined as “the ability of providers and organizations to effectively deliver health care services that meet the social, cultural, and linguistic needs of patients”.28 A newer approach for practising cultural humility, defined as “a lifelong process of self-reflection and self-critique whereby the individual not only learns about another’s culture, but one starts with an examination of her/his own beliefs and cultural identities”, has also been proposed.29

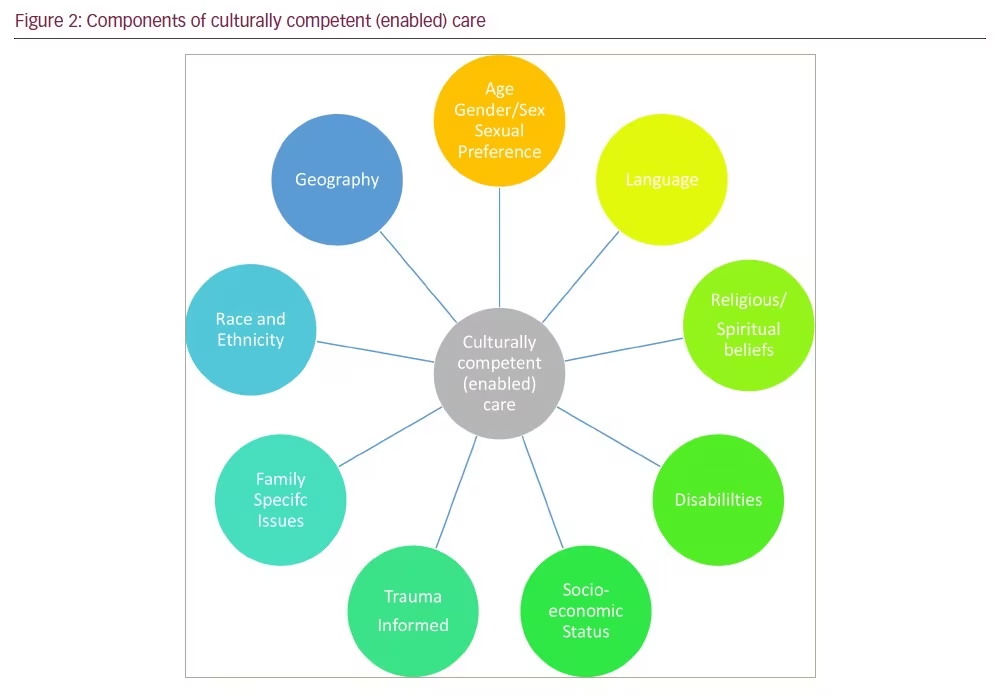

Although most healthcare disciplines are encouraged to provide culturally competent care as part of ethical practice, this is often not well translated into clinical practice. When making clinical recommendations, it is important to consider the individual patient’s cultural components, including age, gender, race and ethnicity, language, culture (including family-specific culture), socioeconomic status, sexual orientation and preference, religious/spiritual affiliation, and disabilities and stage of the disease.30 Geography also plays a large part in the delivery of care; health services may be impacted by internet connections and limitations for travel once patients become less mobile. Figure 2 is a summary of the contributors to culturally competent or enabled care. Personal preferences and patient choice are key aspects of personalized medicine delivery and an integral part of the recently proposed ‘circle of personalized medicine‘ and the previously proposed ‘personalized medicine in non-motor PD‘.30,31

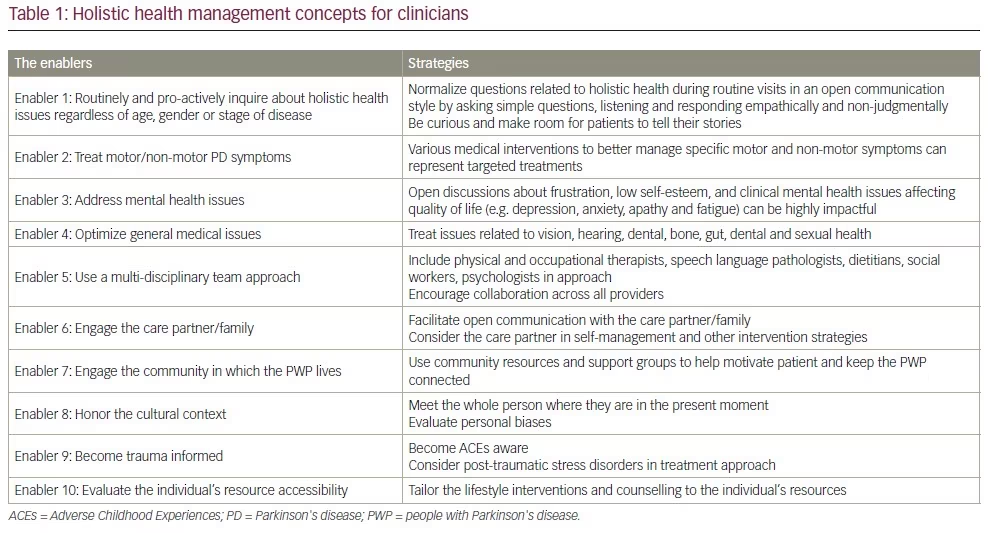

The wellness model approach emphasizes the individual’s environment and cultural context as key components in treatment. It has also been noted that an individual’s competing demands and values may vary in importance over time due to changing life circumstances and stages of the disease.32 Indeed, on any one day or week, the patient may experience a range of symptoms that may either prevent them from participating or enable them to participate in these lifestyle choices. When addressing holistic health, culturally informed care can guide further assessment and significantly change treatment recommendations and adoptability. For example, the wellness model from the First Nation’s Tribe perspective (Indigenous people of North America) includes the land, nature, the ancestors and other nations as model components.33 A traditional healer or leader in a faith community may be critical to healthcare delivery. Other areas in which cultural perspectives are particularly important to acknowledge include attitudes toward ageing, caregiving, dying and mental health, which can often be heavily stigmatized.34–37 A vital component in facilitating collaboration and trust between physicians and their patients is for physicians to actively listen to patients about what they understand about their disease and what caused it. Some people may believe that the person’s past actions may be the cause of their disease, which may contribute to an additional burden of guilt or shame for PWP.38 It is important to understand their values and beliefs while addressing their fears and concerns. This approach is especially important towards the end of life, when a patient’s spiritual and religious beliefs may become even more central and impact the preferred place of death or advanced care planning. These types of discussions are often encouraged in palliative care settings but definitely have value in PD management throughout the disease trajectory. In some cultures, the decision regarding which family members are told the truth about medical issues and who can be engaged to help decide on treatment options can be overly complex.39 Fostering open dialogue with the patients allows physicians to appropriately apply their expertise in ways that positively impact patient outcomes. Positive holistic health management can be facilitated by several strategies. Table 1 displays some suggested methods for how clinicians can facilitate patient wellness.

The role of holistic health in wellness

The conventional approach to care for PWP focuses largely on physical health and motor symptoms. Acceptance of non-motor issues as a significant contributor to quality of life in PWP is a newer concept.40 An emphasis on mental, psychosocial and spiritual health has been relatively undervalued to date, despite there being many excellent reviews on motor and non-motor symptoms in PD.41,42 Here, we focus on the biopsychosocial aspects of health. The concept that mental health is more than the absence of psychiatric illness is consistent with wellness. Mental health, as defined by the WHO, is “a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community”.43,44 Mental health is a collection of positive attributes maintained by psychological skills that help one adapt to the demands of life; it is a key determinant of wellness and should be proactively cultivated to counteract the burden of PD.41 Additionally, general medical health is also important, as issues such as dental, gut, bone health, poor vision, falls and frailty also need to be addressed to ensure that PWP can thrive.27

In PWP, mental health is challenged at several key intervals: at diagnosis, at the onset of significant disability (i.e. the end of the ‘honeymoon period‘) and at advanced disease when function and quality of life are severely decreased. Additionally, it is now possible to disclose a possible carrier mutation status and predict who may develop PD from prodromal symptoms.45 This at-risk or prodromal phase also has potential mental health consequences, especially when the current paradigm does not include potential disease–modifying strategies.46 Optimal mental health can help PWP navigate these challenges and maintain a higher quality of life.

Among the key resources for maintaining mental health are increasing resilience and supporting social connections. Often termed ‘positive psychology’, interventions that promote these resources focus on promoting wellbeing rather than reducing pathology.47–50 Resilience can be understood broadly as successfully adapting to adversity or flourishing despite adversity.51 Resilience was highlighted as a core area of focus by the WHO’s European policy framework for health and wellbeing, which stated that for people to thrive, resilience must be strengthened.52 Several studies have identified a positive relationship between higher resilience and better quality of life. Ultimately, resilience has been described as one of the most important positive attributes for facilitating the ability to adapt to change and maintain flexibility to meet new demands when faced with adversity.53 Resilience has not received much attention in PD.54,55 However, in other disease states, hope and resilience have been associated with better and more sustained coping with a chronic illness.56–58 In PD, higher resilience is correlated with a lower disability, better quality of life and less apathy, depression, and fatigue,55 which suggests the need for better cultivating these positive attributes in this chronic neurological disease.

Social connection

Strong social networks, or connections with friends, family members and community, also contribute to wellness. Social isolation and loneliness have been associated with higher disease burden and decreased quality of life in PWP.14 PWP may develop a vicious cycle in which they feel stigmatized and then become isolated, which can subsequently worsen their motor and non-motor symptoms, leading to further isolation and loneliness. Research on social connectivity has shown that it is important to create meaningful relationships not only in intimate spheres (with a spouse or romantic partner) but also in relational (friends circle) and societal spheres with a community of people who have a similar purpose and interests (e.g. Parkinson’s support groups, religious groups).59 A supportive social network has been shown to prolong independent living, reduce morbidity and mortality, and improve coping ability in individuals with chronic diseases.60,61 In PD, social support has been linked with decreased stigma, depression and anxiety.62–64 It is also associated with better emotional wellbeing, communication, life satisfaction and positive affect.64,65 Specific activities, such as music and dance-based interventions, have been shown to improve emotional and social wellbeing and should be considered for increasing wellness in PWP.15

PWP may experience a change in their social functioning due to PD symptoms (e.g. tremors, facial masking and neuropsychiatric symptoms) or may withdraw from their social roles after PD diagnosis.66 Programmes promoting social support networks for PWP and participation in support groups can improve coping ability and quality of life in this population.67–69 Social support is also helpful in facilitating accountability for lifestyle modifications; individuals completing interventions with a social support component demonstrate increased motivation to adhere to recommended behaviours because they are accountable to someone else.70 Using social prescribing to proactively identify patients at risk for loneliness or depression and connecting them with social support is a promising new intervention that is gaining interest.71

Lifestyle and self-management

From a global health lifestyle perspective, healthy behaviours such as exercise, a healthy diet (i.e. Mediterranean diet), staying hydrated and sleeping well at night are key for PWP to thrive.12 Exercise is medicine in healthy ageing and in PD. Exercising for 30–60 minutes per day, 5–7 days per week, including cardio-based exercises, is beneficial for physical and mental health.72 Having the agency to choose how and which lifestyle modifications to implement may improve compliance.

Self-agency

Essential to self-agency (i.e. one’s capacity to achieve desired goals) is a person’s perceived ability to maintain some control over their own functioning and to meet situational demands, which is best understood as self-efficacy.73 It has been proposed that self-efficacy positively affects behaviour via cognitive processes (e.g. planning for the future), motivational processes (e.g. commitment to desired goals) and controlling negative affective processes (e.g. fear of failing).12,73 Self-agency has been shown to improve quality of life.12 A recent review stated that the ultimate goal of health in PD is to support PWP in self-management and their ability to participate in activities that are meaningful to them.74 There has been a new focus on the role of patient participation in their own health, including adopting a healthy lifestyle that involves regular exercise and an appropriate diet and involving the PWP in medical decisions based on education and physician guidance.13 Wellness strategies to support holistic health include resilience training (e.g. improving the ability to manage physical, emotional and psychological health) and empowering patients by giving them a sense of agency through cognitive behavioural therapy, coaching or mindfulness classes. These important tools should be available to all PWP, yet there has been a lack of study in this area. Furthermore, whilst a number of self-management strategies are promising, they need to include the care partner and peer support in their adoption.75 Patients want free (or affordable), transportable and understandable wellness strategies and tools for empowering themselves to take control of their own health. Counselling and education on modifiable lifestyle choices, including sleep, diet, multimodal and exercise-based strategies (including dance), mind–body approaches and social connection should be available to all PWP from diagnosis.

Historically, there has been a disproportionate focus on pharmacological interventions for treating mental health issues in PWP. However, many patients would like an alternative to adding another pill.76 Latinx, Black, and other ethnic minorities, as well as women, have been more interested in non-pharmacological approaches to treating PD, and this may serve as an entry point to building a rapport with PWP prior to offering them pharmacological treatments.77 It has been proposed that there should be an emphasis on early assessment to allow for effective psychosocial management from the point of diagnosis through to palliative care.22–24

When prescribing these self-management strategies to patients, it is important to evaluate their resource accessibility. The shame associated with a lack of access to these recommended lifestyle interventions has been described in the literature.78,79 Clarke and Adamson highlighted how current exercise recommendations ignore individual social factors, including the location or socioeconomic status.80 A lack of access to specific wellness prescriptions can induce feelings of shame for PWP, which can create additional barriers to achieving wellness. For example, not all individuals can afford gym memberships, and some may experience greater difficulty in maintaining a healthy diet if they are living in a food desert. Considering the individual‘s access to resources could greatly impact patient wellness.

In addition to shame related to the completion of clinician–recommended intervention activities, PWP can experience shame related to their PD diagnosis. Previous research has identified that shame and embarrassment in PD can develop from PD symptoms, increasing disability and worsening body image.81 This shame can contribute to several negative outcomes, such as social withdrawal, reduced quality of life and depression.81 Fortunately, some interventions to reframe maladaptive thinking have been successful in reducing shame in individuals with high shame and self-criticism.82 These interventions should be considered for PWP. The ultimate goal of any wellness strategy is to help the patient feel in control of their own health by making lifestyle choices that will help them to achieve a better quality of life and a higher level of functioning. This goal should be achieved by giving a solid framework for clinicians, PWP and their loved ones to understand the progressive nature of PD and the complexity of its symptoms. Whilst educating and empowering PWP to live better is important, we do not want to add any additional shame or guilt if they do not feel well enough to adopt these lifestyle changes.

We have proposed a framework around which to care for PWP using lifestyle approaches. In the current healthcare environment, with a shortage of movement disorder neurologists worldwide, it is clear that all of this change cannot be the sole responsibility of the patient or the clinician, but rather it lies in a partnership. We propose engaging a multidisciplinary team (Figure 1) and including support groups and community groups, clinicians, PWP and their loved ones as part of a push for change. Educating all providers who are in contact with PWP from diagnosis is part of this message, including primary care physicians and allied health professionals. Using word of mouth, the internet and social media is key to circulating the message behind a wellness prescription, which includes the importance of exercise, diet and social connection as part of medicine, is key that can be accessed even without a physician referral. This approach will need the allocation of additional resources, including specialized training and education for healthcare providers, and the creation of accessible, community-based resources for PWP in order to be implemented.

Conclusions

In summary, addressing holistic health using a wellness-based model invites a culturally informed, multidisciplinary approach, ranging from pharmacological and medical treatments to social, psychological and lifestyle interventions that can be chosen by the patient in concert with their healthcare team and family. The desired outcome may represent not just a decrease in overall physical dysfunction but an experience of thriving due to improved self-efficacy and social connection.