Migraine is a common and disabling condition with substantial health and socioeconomic implications. Approximately 1.04 billion people worldwide have migraine disease.1 The condition disproportionately affects women, with 19% of women versus 10% of men reporting a history of migraine.1 Migraine is the second leading cause of years lived with disability across both genders and all ages; further, it is the leading cause of years lived with disability among women aged 18–50 years.2,3 In the USA, 91% of people with migraine experience functional impairments related to their disease. Overall, 31% of patients with migraine have reported missing at least 1 day of work or school over 3 months due to migraine symptoms.4,5 Migraine headache incurs an estimated cost of $13–17 billion dollars annually in the USA, with $9.2 billion of that cost resulting from direct healthcare expenditure.6,7

Although the number of acute and preventative migraine medications has increased over recent years, there are several treatment gaps in terms of the availability of sustainable, effective migraine therapies. Treatment gaps in efficacy, tolerability, comorbidities, convenience, cost and personal preference have fuelled patient interest in safe, effective, non-pharmaceutical options for migraine management.8–14

External trigeminal nerve stimulation (e-TNS) is a non-invasive, non-drug option for the acute and preventative treatment of migraine. The device, which is marketed under the trade name CEFALY® (Cefaly, Seraing, Belgium), has received clearance from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the acute and preventative treatment of migraine. This overview reviews the current literature on the efficacy and safety of e-TNS therapy, its role in migraine treatment and future directions for use.

Mechanism of action

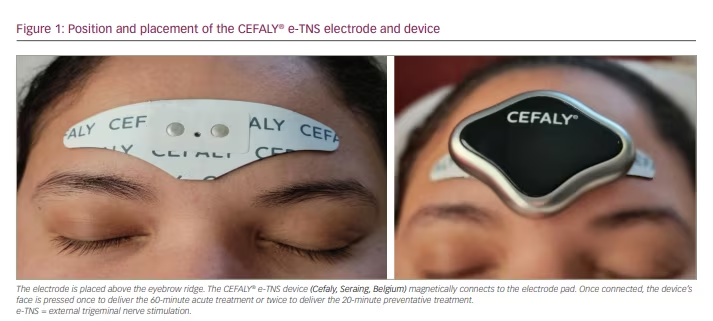

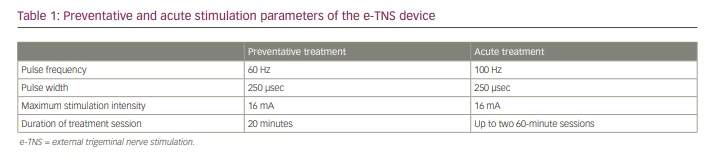

E-TNS, which is also referred to as transcutaneous supraorbital nerve stimulation, percutaneously stimulates the supratrochlear and supraorbital branches of the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve.15 Patients apply a self-adhesive electrode pad to their forehead, above the eyebrows (Figure 1). The electrical generator magnetically connects to the electrode and, when activated, the device provides biphasic rectangular impulses with a zero electrical mean. Once connected, the user can select one of two treatment programs: a daily 20-minute session to prevent migraine attacks or a 60-minute treatment for active migraine attacks. Recent findings from a randomized sham-controlled phase III clinical trial (A phase III trial of e-TNS for the acute treatment of migraine; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03465904) demonstrated the efficacy of using the acute treatment twice for a total of 120 minutes in 24 hours.16 The stimulation parameters for each setting are summarized in Table 1.

The precise mechanism by which e-TNS treats migraine is unclear. Proposed mechanisms suggest both peripheral and central antinociceptive effects. The supratrochlear and supraorbital nerves – branches of the trigeminal nerve that are stimulated by e-TNS – are well established in migraine pathophysiology.17 Another proposed mechanism suggests that e-TNS results in segmental attenuation of nociceptive activity at the spinal trigeminal nucleus. This theory proposes a ‘pain gate’ control mechanism of nociceptive activity.18,19 A study by Aymanns et al. demonstrated reduced nociceptive blink reflexes, a surrogate marker for activity at the spinal trigeminal nucleus, following low-frequency e-TNS.20 However, this finding has not been replicated with higher-frequency stimulation (60 Hz), and further validation of this proposed mechanism is necessary.21,22 In healthy volunteers, high-frequency (120 Hz) e-TNS has been reported to result in transient sedative effects.23 A study by Magis et al. demonstrated the normalization of hypometabolism in central pain-modulating regions on fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography after 3 months of e-TNS preventative therapy.24 In addition, a sham-controlled study by Vecchio et al. showed reduced laser-evoked potentials of the anterior cingulate cortex following a single 20-minute e-TNS session.25 Collectively, these findings provide some evidence that e-TNS therapy alters central neuromodulatory behaviour; however, additional research is needed.

Efficacy of external trigeminal nerve stimulation in preventing migraine

The initial pilot study of e-TNS therapy for the prevention of episodic migraine was conducted at the University of Liege, Belgium, in 2009.26 Eight patients with at least 1 year history of episodic migraine applied daily 20-minute e-TNS for 3 months. Four patients opted to continue therapy after the trial because their migraine attacks had reduced in frequency or pain intensity. The mean migraine attack frequency had decreased from 3.9 to 2.8 attacks per month; however, this finding failed to reach statistical significance (p=0.2).26

E-TNS received initial FDA cleared for migraine prevention in people aged 18 years and older in 2013 following the results of the randomized, double-blinded, sham-controlled PREMICE study.15,27 Compared with sham stimulation, e-TNS was associated with an 18.7% reduction in migraine attacks, a 29.5% reduction in migraine days and a 37% reduction in acute migraine medication use. In addition, 38.2% of patients treated with e-TNS experienced a 50% reduction in migraine frequency, with this group reporting a 75% reduction in acute migraine medication use.

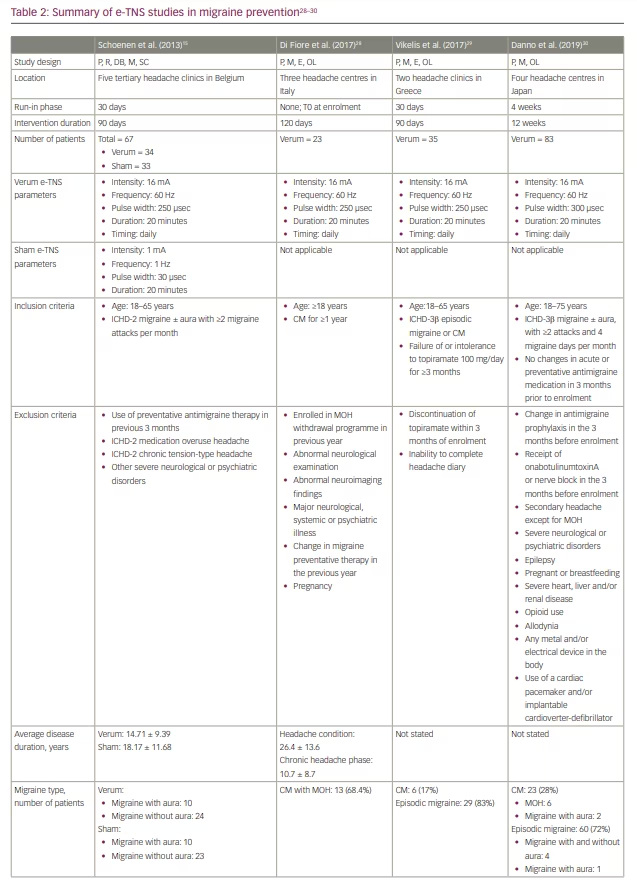

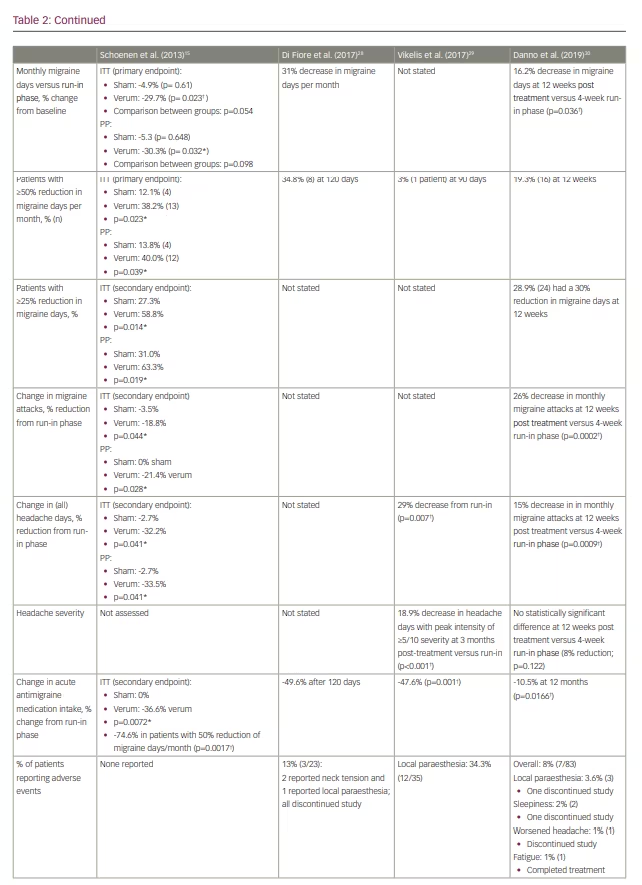

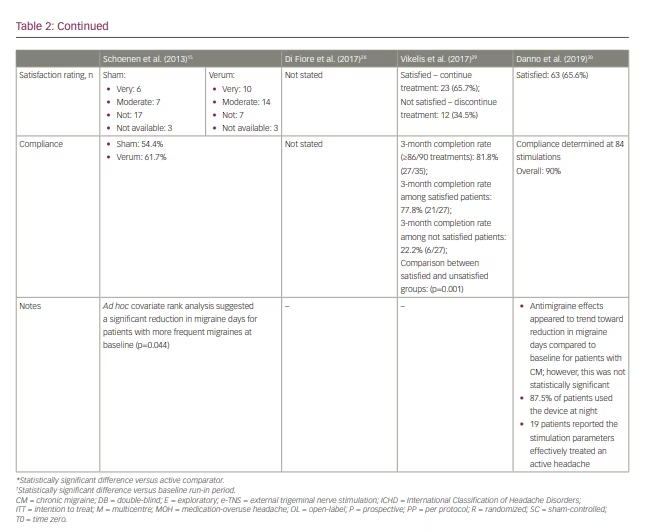

Several subsequent open-label studies have examined the efficacy of e-TNS in preventing chronic migraine and medication-overuse headache (Table 2).28–30 The findings suggest a favourable response to e-TNS; however, additional randomized controlled studies are needed to elucidate the role of e-TNS as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy in chronic migraine prevention.

Efficacy of external trigeminal nerve stimulation in the acute treatment of migraine

In the initial 2009 pilot study, 10 patients applied 20 minutes of e-TNS using the acute treatment setting (100 Hz frequency, 250 µsec pulse width, 14.99 mA stimulation intensity or maximum tolerance) for up to three migraine attacks (30 total migraine attacks).26 Although four (13%) of the migraine attacks completely resolved and the intake of acute migraine medication was delayed in six attacks (20%), there was no response in 17 (57%) and worsening pain in three (10%) attacks; these findings lead the authors to conclude that acute e-TNS was not effective as a monotherapy for acute treatment for migraine.

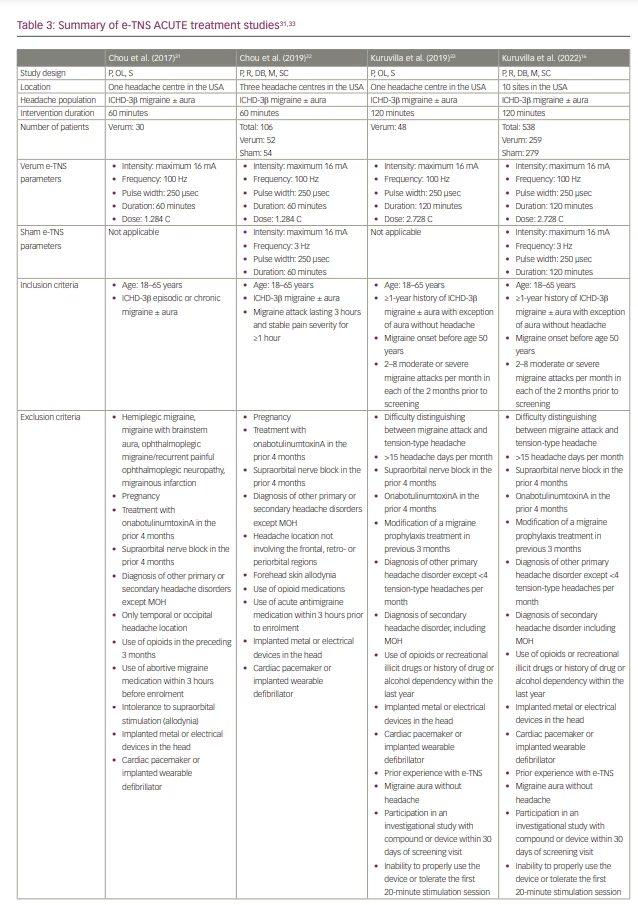

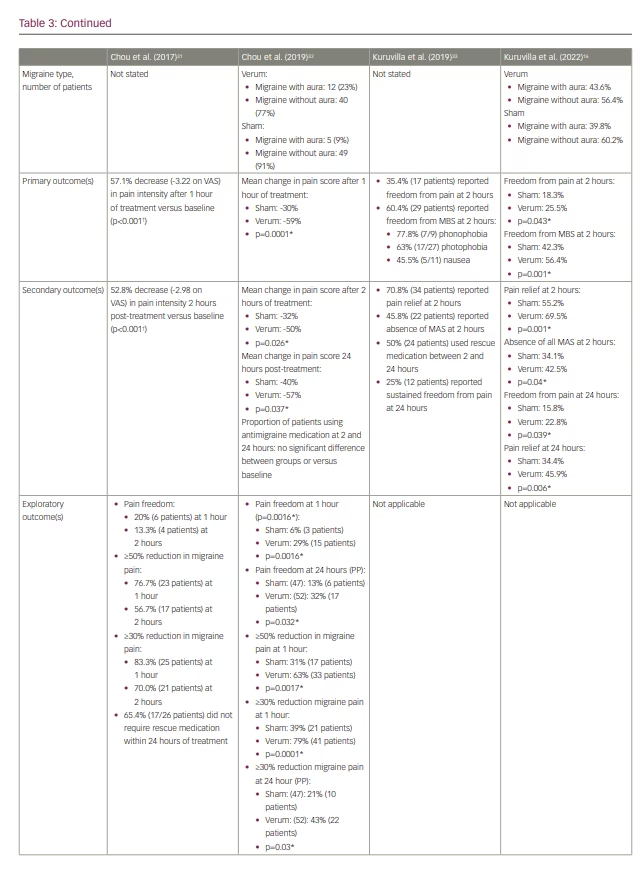

The initial lack of efficacy was attributed to the short duration (20 minutes) of the acute treatment. In 2017, Chou et al. conducted an open-label trial of 60-minute acute stimulation, which demonstrated a mean 57% reduction in migraine severity from baseline, as measured using a visual analogue scale (Table 3).31

E-TNS received FDA clearance for the acute treatment of migraine attacks following the results of the randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled ACME trial (Acute treatment of migraine with e-TNS; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02590939).27,32 The results demonstrated a statistically significant 59%, 50% and 57% reduction in mean migraine pain severity after 1 hour, 2 hours and 24 hours, respectively, following a 60-minute acute e-TNS treatment compared with sham stimulation. In addition, 63% of patients experienced a 50% or greater reduction in migraine severity, and 29% reported pain freedom after 1 hour of e-TNS. Overall, 32% of patients experienced sustained pain freedom for 24 hours in a per-protocol analysis. The results of the ACME trial provided evidence that the 60-minute duration of acute e-TNS therapy is an essential parameter in providing relief for migraine attacks.

In 2019, an open-label trial examined the efficacy and safety of a 2-hour e-TNS therapy to treat migraine attacks in the out-of-hospital setting (Table 3).33 The results revealed pain freedom at 2 hours in 35% of patients; notably, 25% of patients had sustained pain freedom at 24 hours, and 60% reported resolution of migraine-associated most bothersome symptom (MBS). These findings were validated in the randomized, sham-controlled TEAM clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03465904).16 Among 538 patients included in the study, the percentage of patients with pain freedom at 2 hours was 7.2% higher with the 2-hour e-TNS versus sham stimulation. In addition, the rate of patients with resolution of MBS was 14% higher in the 2-hour e-TNS group compared with the sham stimulation group. The percentages of patients reporting pain relief (69.5%) and absence of all migraine-associated symptoms (42.5%) at 2 hours and sustained pain relief (45.9%) and pain freedom (22.8%) at 24 hours were all significantly higher in the 2-hour stimulation group compared with sham. The TEAM study provides further evidence for the efficacy of 2-hour e-TNS in acute treatment in providing sustained pain freedom, pain relief and resolution of MBS in the out-of-hospital setting.

Tolerance, safety and compliance

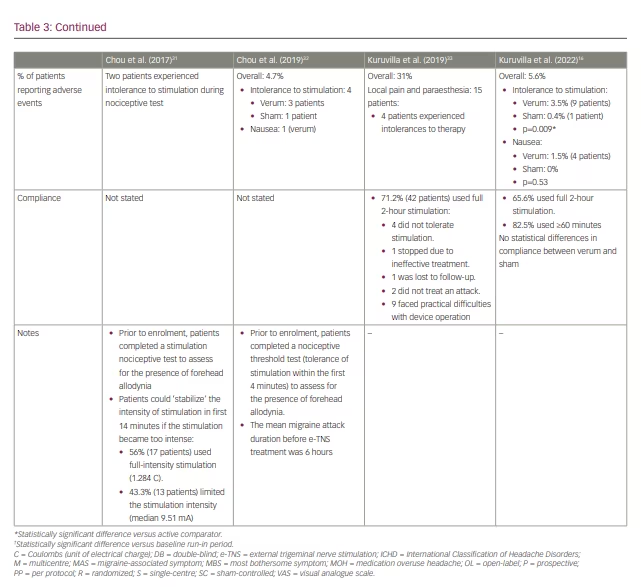

Overall, e-TNS is a safe and well-tolerated therapy without serious adverse effects. The reported rates of adverse events with e-TNS in randomized clinical trials range from 0 to 5.6%, with all events being transient and fully reversible within 24 hours of treatment cessation without additional intervention.15,16,32

The most common adverse event, and the most common reason for discontinuation, is intolerance to stimulation-related paraesthesia.16,26,28–33 Cephalic allodynia is a primary factor in stimulation-related intolerances among patients experiencing an acute migraine attack.34,35 Inclusion criteria for e-TNS studies to date have required patients to complete a nociceptive test to assess for allodynia precluding tolerance to the maximum stimulation intensity (16 mA). In clinical practice, the e-TNS device has a ‘stabilization feature’ that allows the patient to plateau the stimulation intensity within the first 14 minutes if paraesthesia becomes too intense.36 This feature may mitigate stimulation intolerance and provide an opportunity for acclimatization among new users.

Sleepiness and sedation with e-TNS therapy is also a common side effect. However, this may be clinically beneficial in patients with comorbid insomnia, which is a common and potentially bidirectional risk factor for migraine.23,37 Some patients may experience increased nausea and emesis, even the absence of migraine headaches, associated with treatment.

Treatment compliance with e-TNS treatment for migraine is closely related to tolerability and satisfaction. Most patients report high satisfaction and excellent tolerability.15,38 In a postmarketing survey of 2,313 patients, 2% of respondents stopped e-TNS therapy because of adverse events, and approximately 9% of patients with suboptimal compliance reported adverse events.35 These findings highlight the importance of patient education to reduce the risk of adverse effects such as pain and paresthesias to optimize tolerability and compliance of e-TNS stimulation and achieve favourable migraine outcomes.

Role of external trigeminal nerve stimulation in migraine management

E-TNS is a safe and effective, non-medicinal therapy for the prevention and acute treatment of migraine and migraine-associated symptoms. The American Headache Society recently published updates on the potential role of e-TNS as an adjuvant or monotherapy in acute and preventative migraine management.39 E-TNS may serve a unique role for patients with migraine who fit the following criteria:

- have an inadequate response to oral antimigraine medications

- may be at risk of medication overuse headache

- require adjunct antimigraine therapy

- prefer to avoid medications

- have poor tolerability of or contraindications to oral, injected or infused antimigraine therapies.

E-TNS is uniquely appropriate for patients with migraine who prefer or must consider non-pharmaceutical approaches to migraine treatment. The good adverse event profile and transient nature of minor adverse events are attractive features for patients who are prone to adverse events with conventional pharmaceutical therapies. In addition, e-TNS has no interactions with other migraine medications, making it an excellent complementary option in the stratified approach to migraine treatment.

E-TNS may have a unique role in the treatment of medication-overuse headache. However, the role of e-TNS in patients with chronic migraine is unclear. Although open-label studies provide some evidence for e-TNS in chronic migraine, allodynia can be a substantial limiting factor in compliance with and tolerability of e-TNS in these patients. E-TNS is contraindicated in patients with a cardiac pacemaker or an implanted or wearable defibrillator. It is also contraindicated in patients with intracranial metallic or electronic devices.

In 2020, e-TNS received FDA clearance for over-the-counter availability, thus allowing broad access of the device to patients without a prescription.27 Despite the clinical applicability and versatility of e-TNS, lack of payor coverage is a leading barrier in providing access to this device and other neuromodulatory therapies for many patients with migraine and may contribute to disparities in migraine outcomes.40

Conclusions and future areas of study

It is reasonable to recommend e-TNS to patients for the prevention and acute treatment of migraine; currently, it is the only device available over the counter for patients in the USA. Although studies have demonstrated the favourable outcomes and safety of e-TNS in migraine treatment, additional research is needed to fully understand its underlying mechanisms of action and long-term results in migraine prevention and to broaden its potential clinical applications in neurological disease.

Future prospective trials should investigate long-term (≥6-month) efficacy outcomes in migraine frequency. Additional studies might evaluate the consistency of acute treatment efficacy by treating two or three migraine attacks. As a non-pharmaceutical therapy, e-TNS may have a role in medication-overuse headache; however, more studies are needed to elucidate the role of e-TNS in managing chronic migraine. Future trials could also assess migraine-associated disability and quality-of-life measures. In addition, future protocols might investigate whether giving the user added control of the stimulation intensity can improve tolerance and reduce stimulation-related paraesthesia.

Finally, the limited evidence indicating a central mechanism of action of e-TNS suggests a potential for additional therapeutic applications in managing other pain-related and non-pain-related neurological conditions.

Minor post-publication correction: Compliance with ethics statement updated