It has been recognised for centuries that symptoms outside of pain are reported with migraine.1 Symptoms prior to the onset of migraine headache have been called premonitory or prodromal symptoms and the symptoms after headache resolution have been called postdromal or resolution symptoms in the literature.2–4 These symptoms are likely to be a continuum, starting before the onset of headache, and persisting throughout the headache phase, perhaps becoming less noticeable in the presence of moderate-to-severe pain. They can also persist after the resolution of pain before return to normal function, and studies have shown similarities in the phenotype of premonitory and postdromal symptoms.5

These non-painful cognitive, homeostatic and sensory sensitivity symptoms can be disabling and prevent normal function, adding to the morbidity associated with a migraine attack. It is therefore important to recognise their phenotype and relationship to headache, and further to understand their neurobiology. Most research in this field has focused on symptoms displayed before the onset of moderate–severe migraine headache. However, for the purpose of this review we call the symptoms ‘premonitory-like’ as we have observed that they can start at the same time as pain, or occur during the pain itself. Whether symptoms start before or during pain, they are likely to be biologically mediated the same way, regardless of their onset within the migraine timeline; hence the use of this definition here. For the purpose of this review, premonitory-like symptoms will be defined as any nonpainful symptom associated with the migraine attack, possibly predictive of impending headache and starting before the onset of pain, or non-migraine-defining symptoms occurring during the pain itself. Postdrome or resolution symptoms are neurobiologically poorly understood at the moment, and phenotypically not well reported in the literature and will therefore not be included in this review.

It should also be noted that premonitory-like symptoms are often mistaken as migraine triggers; for example, a craving for chocolate may be a premonitory symptom, but patients are likely to interpret this as chocolate often triggering a migraine headache in them.6 Increasingly, the evidence suggests that many of the triggers reported by patients are not reproducible in experimental research, and may actually represent the manifestation of premonitory-like symptomatology.6,7 Therefore, there is an increasing need to understand the mediation of such symptoms, and their differentiation from migraine triggers, to allow patients to understand their condition better and effectively manage their lifestyles accordingly.

Prevalence of premonitory-like symptoms in migraine

The true prevalence of premonitory symptoms among migraineurs is unknown, as most of the studies are retrospective and the numbers reported vary greatly across different studies.8–13 In addition, the majority of the studies performed so far have only looked at symptoms starting before the

onset of headache, the true definition of ‘premonitory symptoms’, rather than looking at the development of such symptoms with or during the onset of pain. Various retrospective studies in the literature have quoted prevalence rates of 9–88%.3,8–18 See Table 1 for a breakdown of studies to date in the literature looking at premonitory symptom prevalence.

Regardless of the prevalence, Giffin et al.16 showed with an electronic diary study that the experience of these symptoms is highly predictive of impending migraine headache. In this study patients were reliably able to predict the onset of headache 72% of the time, after reporting premonitory symptomatology.16 Symptoms have been reported up to 72 hours prior to the onset of pain previously, but the Giffin et al.16 study showed that symptoms occurring within 6 hours of the onset of headache had the highest predictive value, and most symptoms occurred within 24 hours of headache onset.

Two studies have also shown the existence of such symptoms among children and adolescents, even as young as 18 months.17,18 One of these showed a prevalence of 67% in the cohort of 103 children and adolescents with migraine.18 The other study preselected patients who had reported at least one premonitory symptom.17

These studies highlight consistently the presence of these symptoms among migraineurs and their ability to predict impending headache, as well as their presence or development at any time during a migraine attack. These features suggest that the symptoms may not be directly pain-related or mediated by pain, and are likely mediated by additional brain structures outside of the well-recognised trigeminovascular pain pathway.

Phenotype of premonitory-like symptoms

Despite the varying population types used in the studies performed to date, as well as varying methods of data collection, such as patient interview, self-administered questionnaires or electronic diaries, and whether data were collected from the headache clinic or wider population, the phenotype of symptoms reported in adults is largely consistent across these studies (see Table 1).9–16 The most common symptoms seem to be fatigue (see red in Table 1), mood change (see blue in Table 1) and yawning (see green in Table 1). These are consistent across the studies. Other common symptoms are neck stiffness and concentration difficulty.

The most commonly reported symptoms group largely into cognitive- or sleep-related symptoms (mood change, concentration or memory impairment, yawning, sleep disturbance and fatigue), migraine-like symptoms and sensory sensitivities (photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, mild head or eye discomfort and neck stiffness) and other homeostatic symptoms such as frequency of micturition, food cravings and bowel habit change. Paediatric studies have shown that the phenotype in children and adolescents is mostly comparable to that in adults.17,18

Relationship of symptoms to the neurobiology of migraine

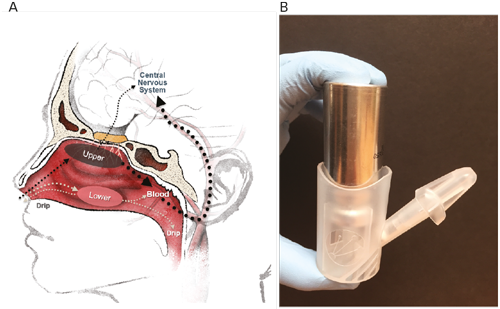

The role of the brainstem as the driver for migraine attacks has been increasingly accepted.19 Various imaging studies in humans have now shown activity in brainstem structures during acute pain.20–24 Premonitory-like symptomatology clearly involves brain areas outside of pain pathways, given the variable phenotype of symptoms produced. The broad groups of symptoms that most of the symptoms reported by patients fall into could help us understand the biologic basis of the symptoms, by considering involvement of the limbic system (emotional change, tiredness and concentration impairment),25 dopaminergic pathways (yawning),26 the hypothalamus (neck discomfort, sleep disturbance, thirst, cravings, frequency of micturition)27,28 and other brainstem areas (nucleus of tractus solitarius and nausea).29

Such theories alluding to the wider neurobiology of migraine led to the first functional brain imaging studies during the premonitory stage of migraine in 2014.29–31 These provided supportive evidence for the early involvement of the dorsal pons, hypothalamus and various cortical areas in migraine attacks, and interestingly revealed early involvement of the brainstem before the onset of pain. These findings confirmed the suspected brain regions hypothesised as being involved in mediating some of the symptoms reported by patients, including an area in the brainstem which seemed likely to be the nucleus of the tractus solitarius mediating nausea.29

The occurrence of premonitory symptoms, their ability to predict an impending headache and the anatomical structures alluded to in imaging studies during premonitory symptoms, suggest that they could provide vital neurobiologic information about the basis of a migraine attack, and important clues about therapeutic development in the future. If we can understand the neurotransmitter systems at play early before the onset of pain, we may be able to understand how to develop targeted therapies that work on these systems and may be able to prevent pain onset at all. Small studies of this type have been performed using domperidone, taken during premonitory symptoms, acting on the dopamine pathway,32,33 and have shown promising results, but larger randomised placebo-controlled trials are warranted.

In addition, triggering studies as a way of modelling human migraine have also increased knowledge in this area. Nitroglycerin (NTG) and pituitary adenylate-cyclase activating protein (PACAP) have been shown to be able to trigger premonitory symptoms in migraineurs, similar to those experienced with spontaneous attacks.34,35 NTG is a well-established migraine-triggering model in the literature,36 but it has not been used extensively yet to study premonitory-like symptomatology. PACAP is newer in migraine research37 and its ability to trigger migraine38 has led to interest in agents targeted against the PAC1 receptor as a possible treatment for migraine.39 In a similar way, the human triggering models may, in the future, allow us to explore newer effective triggering compounds and thereby further study antagonising the exogenous trigger molecules, in the hope of being able to prevent premonitory symptom and pain onset.

Conclusions

Migraine is a disorder of more than head pain, and comprises heterogeneous non-painful symptomatology that can be equally debilitating, and contribute to the morbidity of the attack. These nonpainful symptoms may start hours to days before the onset of pain, or start alongside the pain, and may persist after headache resolution. It is likely from observation of our patients in the clinic that these symptoms are probably under-reported. This is partly due to failure of patient recognition unless asked, and due to physicians not asking about specific symptoms that patients may not themselves have associated with a headache attack, or may have associated with trigger factors rather than premonitory-like symptoms. Recognition of the presence of these symptoms, particularly before the onset of headache, and differentiation of them from true migraine triggers, can help patients understand the wider impact of the attack, and reliably predict the onset of impending headache, as well as allow early and effective headache management. Education about these symptoms, and helping patients understand that these are explained as being part of the migraine attack, can increase understanding of the symptoms, and limit unnecessary misinterpretation of some of these symptoms as migraine triggers and therefore limit unhelpful lifestyle modifications. In addition, in the paediatric population, education about the recognition of these symptoms among parents, teachers and carers, can allow prompt treatment in this population who may not always be able to display or vocalise pain. From a research perspective further understanding of the neurobiologic basis of these symptoms, through functional imaging and through pre-clinical models, will help us understand the regions of the brain likely to be involved, and thereby help with planning future therapeutic clinical trials.

In addition, increasingly studying the symptoms in humans through triggering models, imaging studies and treatment in randomisedcontrolled trials may help us identify future therapeutic targets. Identification of specific neurotransmitter systems in certain brain regions could help development of targeted migraine therapies, in an exciting era when migraine therapeutics has evolved greatly, but there will always be a need for more targeted acute and preventive therapies to help those affected by this disabling disorder with greater efficacy and limited side-effect profiles. Future clinical trials should assess efficacy of the drugs in question in treating associated non-headache symptomatology in migraine, as well as headache, as this can be equally debilitating and impair the quality of life of those affected.