The non-motor symptoms (NMS) of Parkinson’s disease (PD) are common and often not fully appreciated. They are sometimes referred to as non-dopaminergic symptoms, which in some cases may be a misnomer. NMS are present at all stages of the disease, and are potentially a major source of disability. Some of these symptoms, such as dementia, delirium, hallucinations, and psychosis, are important factors in PD patients’ lives and may lead to institutionalisation. As such, they affect not only the individual but also have a social impact.

It is encouraging that the non-motor features of PD have been incorporated into the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) PD quality measures published in 2010,1 as healthcare stakeholders use these measures when making decisions on the allocation of healthcare resources. Out of the 10 AAN quality measures, five concern the non-motor features of PD (see Box 1).

The following two case reports illustrate the impact of continuous dopaminergic stimulation (CDS) on the NMS and social aspects of PD.

Case Report 1

Patient 1, a 57-year-old male family physician, had been diagnosed with PD at the age of 45. After 12 years of PD, his daily regimen was 800 mg levodopa (spread over seven intakes) plus 100 mg levodopa-benserazide hydrodynamically balanced system (HBS). He also took 200 mg tolcapone (three times a day), 100 mg amantadine (twice daily), 1 mg rasagiline (once daily) and 150 mg venlafaxine (once daily).

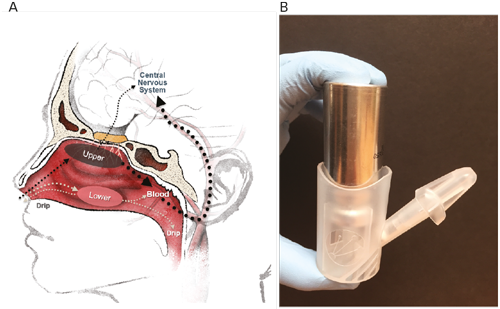

The patient’s motor complications included troublesome dyskinesias, end-of-dose ‘wearing off’, unpredictable ‘on-off’ motor fluctuations, dose failures and delayed ‘on’. His non-motor complications comprised depression, free-floating anxiety, concentration problems, sleep dysfunction, autonomic dysfunction (urinary urgency), sensory dysfunction (hyposmia and pain) and sexual dysfunction (erectile dysfunction and libido loss). The patient’s family was concerned that he might become dyskinetic or drop into a deep ‘off’ when he was outside the home. The NMS were also very troublesome for the patient professionally, with his patients beginning to question his competency. The combination of motor and non-motor complications led him to a forced early retirement and the patient’s social and family life were adversely affected.

To obtain reimbursement from the Belgian authorities for levodopa/carbidopa intestinal gel (LCIG) infusion, a test week is required. The patient completed a test week in November 2009, and in March 2010 approval was obtained to initiate LCIG infusion therapy. All other Parkinson’s medications were stopped. Hisdosages during the first year of LCIG infusion therapy were fairly stable (see Table 1).

To view the full article in PDF or eBook formats, please click on the icons above.