The event was opened by Stephen Pickard (Belgium), President of the European Parkinson’s Disease Association (EPDA), which has 39 member associations from 33 countries, representing more than 100,000 people. Pickard spoke of the latest initiatives to raise awareness of PD and improve the lives of those who are affected by it. One of the major focuses of the EPDA is to empower people with PD and their carers by providing information about the disease so they can understand what is happening and how the treatments are meant to work, and know what to expect and what questions to ask their doctors.

The first scientific session was chaired by Castro Caldas (Portugal) and examined the long-term underlying pathological processes in PD with José Obeso (Spain), before Mary Baker (UK) set PD and its impact on society in an international context alongside other diseases, both neurological and non-neurological.

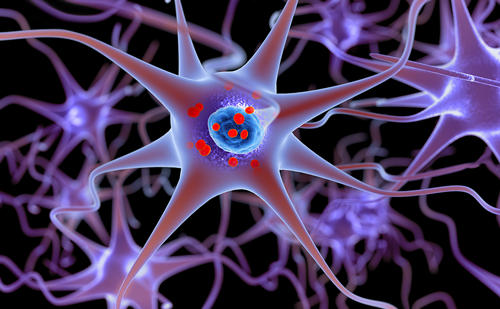

In terms of development of PD, most research over the past decades has focused on the early stages of PD and the attendant motor and neuropsychiatric complications. Treatments have advanced such that replacing the striatal dopamine deficit is now no longer the major challenge. Patients are living longer and will face countless more years with later-stage problems including cognitive impairment, dementia and equilibrium difficulties. This is related to a change in pathology, where the characteristic Lewy bodies are now found outside the substantia nigra in other areas such as the amygdala and the ventral temporal cortex. Obeso proposed that rather than being the result of a single insult to the brain followed by a domino or cascade effect, PD is an underlying process that is present all of the time. Although the striatum is most affected, it is not the primary site of pathology of PD – just the initial site. However, deeper understanding of this process – and knowing how and where to intervene – is still lacking.

Baker examined the cost of neurological conditions to society. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the five major neurological disorders are Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, headache/migraine, multiple sclerosis and epilepsy, which together account for 35% of Europe’s total disease burden. The prediction is that within a few decades they will overtake cancer and cardiac disease as a major cause of disability and death. For PD specifically, the majority of the economic cost of the disease is caused by loss of productivity. This loss of independence is even more acute given the societal changes that have occurred in the past 100 years: human lifespan has nearly doubled; since the Great War there has been a decline in the number of single, non-working female relations who can share care duties; and with many European countries now home to people from various diverse communities, there is a need to provide ‘culturally competent care’. From Health Economics to the Tango

Dr Andrew Lees (UK) chaired the second session, which developed some of the themes of the earlier talks. Speaking first, Richard Dodel (Germany) introduced the difficult but increasingly important topic of health economics and the burden of PD. He was followed by Mariella Graziano (Luxembourg), with a lively talk on the role of physiotherapyin keeping PD patients healthy and able to cope with modern life.

Over the last 15 years, health economics has become a big issue acrossthe world as health budgets tighten and authorities focus on evaluating the cost-effectiveness of drugs. There are three categories of cost incurred in medicine – direct, indirect and intangible – and including or omitting one category of costs can have a huge difference on the outcome of an economics analysis. The ‘gold standard’ of health economic assessments is the comparison study, which is increasingly taking the form of a decision analysis model. Performing a comprehensive economic assessment can highlight areas where costs are generated, which often conflicts with what people assume costs the most. For example, it is often thought that the main costs associated with brain disorders are doctors’ salaries and drug prices, but in fact the greatest factor in the economic burden of PD is the cost of sick leave from work, which combined with early retirement accounts for 40% of the total. Dodel’s data so far indicate that the annual cost of PD is roughly €20,000 per patient, and that treating patients with motor fluctuations or dyskinesias costs double treating those without. However, it is clear that good-quality health economic data are lacking in most European countries.

Graziano spoke about teaching patients to cope with falls and balance problems, which are notoriously unresponsive to current therapeutics. hysiotherapy interventions are a relatively new area within PD treatment, pioneered by Professor Iansek from Australia. The aim is to improve activities of daily living (ADL) related to mobility in the core areas of prevention of inactivity, gait, posture, transfers, reaching and grasping and balance and falls, looking at both axial symptoms and drug-related complications. Each therapy is tailored to the patient’s needs according to the stage of disease and, often in conjunction with their carer, realistic goals will be set. Components include cardiovascular exercise and strategies for getting up from chairs or the floor, moving between rooms or through a narrow space, drinking and eating and maintaining good posture. The essential coping strategy is to cut the long sequence of movements into short, manageable, memorable stages. Such strategies provide a highly cost-effective way to help patients get on with their lives. Professionals are not the only ones with coping strategies; patients often come up with their own innovative ways to deal with movement issues, and with the help of the EPDA these can now be shared using a dedicated website and CD-ROM. Tricks were collected at EPDA physiotherapy workshops across the world, and include using a ball to control tremors and freezing, loosening up with running or dancing and using visual cues such as a torch or even just a line to aid movement.

Quality of Life Issues

Chaired by Reinhard Dengler (Germany), the first session of the afternoon focused on quality of life. Patricia Limousin (UK) spoke first, about quality of life and the influence of ageing on the success of deep brain stimulation (DBS). Following her, Johan Samanta (US) looked at quality of life in advanced PD patients treated with levodopa infusion therapy. Most parkinsonian off-state symptoms, particularly motor symptoms, can be improved with DBS of the subthalamic nucleus (STN). However, to these improvements necessarily translate into better quality of life? It transpires that there is a clear tendency for some quality of life subscores to improve reliably – particularly mobility, ADL and bodily discomfort. Three domains that typically do not improve, and often worsen, are social support, cognition and communication. Upper age limit is a controversial subject for DBS, and there is a lack of consistency regarding age within clinical trial design. Limousin’s review revealed that STN-DBS does improve quality of life for all PD patients in the medium term, but these improvements are almost exclusively in domains related to motor function. Older patients (>60 years of age) are already at greater risk of balance difficulty and cognitive decline, as well as risk from surgery, and are likely to benefit less.

Samanta also looked at quality of life, commenting that keeping patients in an ‘on’ state would appear to be a crucial element. While a number of studies have emphasised the importance of mental and mood issues, these factors are themselves affected by motor state and drug therapy. Dyskinesias, for example, inhibit the social lives of patients and therefore affect quality of life. However, non-motor complications also affect quality of life, and patients may not initially realise they are connected with PD. With oral levodopa therapy there is a smooth clinical response for the first three to five years, followed by a slow deterioration of benefit and the rise of motor fluctuations and dyskinesias. Over the past decades it has been shown that the relationship between these effects and levodopa is due to the oral, intermittent method of delivery rather than the drug itself. Thus, the concept of continuous levodopa infusion to the duodenum to achieve stable serum levodopa concentration was born. Studies of levodopa confusion have shown improvements in off time, dyskinesia severity, ADL ratings and the Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire – 39 item (PDQ-39) quality of life scale, although more long-term data are needed.

Treatment Algorithms

The final session of the day was chaired by Angelo Antonini (Italy), opened by Francesc Valldeoriola (Spain) and concluded with Jens Volkmann (Germany). The session focused specifically on duodenal levodopa infusion (Duodopa) and its place within the treatment algorithm of PD patients.

Valldeoriola spoke about his experience, of less than two years, of using Duodopa at the University Hospital in Barcelona. He has been involved in a trial of Duodopa in 15 patients, with a high median age of nearly 69 years and a long disease duration of nearly 18 years, both of which are higher than the DBS average. The trial is ongoing, but preliminary data suggest a trend of 87% reduction in off time and 52% reduction in dyskinesia, along with striking improvements in Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) scores and smaller improvements in ADL. The procedures were not without complications: there were eight related to percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG), nine to the device and 10 to the infusate, and two patients required 24-hour continual infusion. Additionally, in four patients the team observed new ‘biphasic’ dyskinesias immediately after the device was switched off for any reason. Biphasic dyskinesias involved rhythmic movements of the legs and were of severe intensity, painful and difficult to manage. Extra levodopa doses helped to reduce them, while dose reduction increased them. In general terms, Valldeoriola confirmed that continuous infusion helps relieve dyskinesia but does not completely eradicate it. His findings appear to be confirmed by the experience of other hospitals in the Barcelona area. Volkmann’s talk investigated the issue of when is the right time to look at alternatives to oral levodopa – is there a ‘too late’ or ‘too early’? The options at this point are either DBS or infusion (with a dopamine agonist or levodopa). A 2006 review by the American Academy of Neurologyfound modest evidence that DBS improves motor function, fluctuations and dyskinesia but, owing to a lack of controlled trial data available at the time, does not mention Duodopa. Furthermore, the clinical reality is that DBS does not reach its theoretical maximum effect in everyone. Patient selection and electrode location have a huge impact on the outcome, as does the experience of the surgeon. Volkmann’s own experience of Duodopa lead him to recommend its use in patients who do not fulfil the strict inclusion criteria for DBS, but not those with severe dementia, who are non-compliant, have poor family support/nursing care or who are frail. Notably, despite the disease-modifying advantages of Duodopa, some patients feel there is stigma attached to having to use an externally mounted pump, which is not present with DBS. Thus, people in different age groups need to be counselled appropriately, and patient preference should always be taken into account.

Summary

All eight talks stimulated great debate among delegates. The main points raised included the importance of having a full team caring for a patient and not simply one neurologist. In terms of pathology, the role of Lewy bodies was discussed, and there was a call not to be premature in drawing conclusions from their presence in foetal cell grafts. Within health economics, there was comment on the cost of checking costs: it was claimed that up to two-thirds of hospital costs are not directly related to treating the patient. An alternative way of measuring quality of life, related to pre-determined goal attainment, was mooted by one delegate. There was also recognition of the need for a compromise in treatment, given the difference between the ‘ideal’ patients defined in clinical trials and those who really exist. Overall, an excellent, progressive forum.