This article reviews the potential role of delayed gastric emptying in patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) and morning akinesia. This can result in impaired motor function and impairment of a range of nonmotor functions, as shown in a recently reported early morning OFF study.1 Morning akinesia can have a significant impact on quality of life (QoL) and delay a patient’s ability to carry out their normal daily activities.2 Treatment strategies for morning akinesia remain suboptimal. Gastrointestinal (GI) dysfunction (including gastroparesis) is a common feature of PD. Gastroparesis can occur throughout the disease duration, and in some cases may even precede diagnosis.3,4 GI symptoms of gastroparesis not only impair patients’ QoL but can also impact the onset of oral levodopa, by delaying its delivery to the small intestine where it is absorbed.5,6

Delayed ON and Morning Akinesia in Parkinson’s Disease Patients

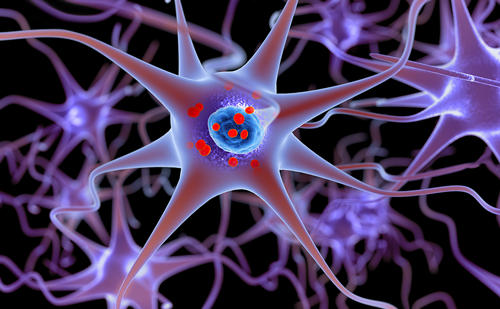

In PD, motor symptoms reflect severe degeneration of nigrostriatal dopaminergic pathways with intracellular aggregation of synuclein (i.e. Lewy bodies).7 Non-motor symptoms are often poorly understood and inadequately treated, but are thought to arise from more diffuse involvement of the central, autonomic and enteric nervous systems.8 Widespread involvement of the GI system is common in PD, with synuclein and Lewy bodies demonstrated throughout the enteric nervous system, including within myenteric neurons.

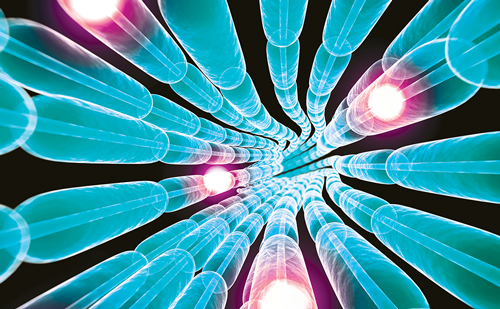

The treatment of PD motor symptoms relies on oral levodopa, which must be emptied from the stomach and absorbed in the proximal small intestine. Gastroparesis causes delayed gastric emptying of levodopa with a delay in its delivery to the duodenum, resulting in the clinical phenomenon of delayed ON after a levodopa dose.9 Initially, the therapeutic effect of each levodopa dose is rapid, reliable and sustained (onset around 20 minutes and a long duration response). However, after several years of levodopa treatment, the long duration response becomes replaced by a short duration response, and OFF periods emerge.10,11 While OFF periods can be treated with several adjunctive medications, delayed onset of the next levodopa dose can significantly increase OFF period duration.11

Morning akinesia due to delayed onset of the first daily levodopa dose may occur in up to 50 % of patients receiving levodopa after several years.12–14 Morning akinesia can significantly affect QoL in PD patients, consequently impairing the ability to perform daily activities, such as arising from bed, dressing, bathing, toileting, preparing breakfast and getting on with the day’s work.2

Gastrointestinal Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease Patients

GI dysfunction is frequent in PD, and reflects both the underlying synucleinopathy and dopaminergic therapy.3 Emerging data suggest that the underlying neurodegenerative process affects the central, autonomic and enteric nervous systems. Dysfunction throughout the GI system results in frequent, and occasionally dominating, nonmotor symptoms. Features of GI dysfunction include dry mouth, sialorrhoea, dysphagia, oesophogeal dysmotility, gastro-oesophogeal reflux, gastroparesis, constipation and impaired defecation.15 These GI symptoms significantly impair QoL in PD. In a multicentre study in 411 PD patients with and without GI dysfunction, PD patients with GI dysfunction had significantly decreased health-related QoL.5 In a study evaluating QoL related specifically to swallowing, patients with dysphagia reported significantly reduced QoL. Data also suggested a possible association between swallowing, social function and depression.16

Saliva production is reduced in PD, but sialorrhea reflects pooling of saliva in the mouth due to decreased swallowing frequency. Dysphagia develops in approximately 50 % of patients and reflects disruption of both the central nervous system and the enteric nervous system.15 In one large survey, 59 % of patients reported swallowing problems.17 In the NMS Quest study, 30 % of patients had swallowing dysfunction (versus 4 % in control subjects) with an average PD duration of 6.4 years.18 Involvement of the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus can lead to dysfunction of the muscles controlling swallowing, oesophageal dysmotility and gastroesophageal reflux.19 The presence of Lewy bodies in the myenteric plexus and intrinsic neurons contributes to oesophageal dysmotility and to constipation.

Constipation is common in PD, and probably reflects intrinsic, enteric and autonomic dysfunction, dehydration and medications taken for PD and concomitant conditions. Impaired defecatory mechanisms contribute to constipation, reflecting the involvement of somatic and pelvic parasympathetic nerves and pelvic floor dysfunction.19

Medications used to treat PD contribute to GI dysfunction, including levodopa, dopamine agonists, anticholinergics, amantadine and inhibitors of monoamine oxidase (MAO) and catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT).20Levodopa can increase gastric acid secretion,21 impair gastric relaxation21and delay gastric emptying.22 Levodopa-induced dyskinesia can speed gastric emptying.23 Other PD medications can also increase acid secretion, and can influence gastric emptying. Anticholinergics and amantadine also commonly cause dry mouth and constipation, while COMT inhibitors can cause diarrhoea.24

Gastroparesis in Parkinson’s Disease Patients

Gastroparesis, where the stomach takes longer than normal to empty, is common in both early and advanced PD, and may even be a marker of pre-clinical PD.25 However, a recent review concluded that while delayed gastric emptying is reported frequently in PD, data are limited on its prevalence, relationship to the underlying disease process, relevance to PD management and optimal treatment of gastroparetic symptoms.26

Symptoms of gastroparesis can overlap with adverse effects of PD dopaminergic medications, such as nausea. Gastroparesis may result in a variety of GI symptoms, including nausea, post-prandial bloating, abdominal discomfort, early satiety, nausea, vomiting, weight loss and malnutrition.15,26 A recent survey of PD patients found that 24 % reported nausea and 45 % reported bloating.27 In addition to causing GI symptoms, gastroparesis in patients with PD may also cause motor fluctuations, including delayed ON and morning akinesia, by delaying the arrival of oral levodopa to intestinal absorptive sites.9,15,23,28,29 Several studies have demonstrated a significant relationship between gastric emptying and levodopa pharmacokinetics in PD patients, suggesting that delayed gastric emptying contributes to delayed ON and other motor fluctuations.6,30,31

Evaluation of motor fluctuations in patients with PD should also consider GI dysfunction. A review of symptoms should include checking gastroparetic and other GI symptoms. History can identify patterns of OFF periods, including time-to-ON, delayed ON, morning akinesia and dose failure. In particular, clinicians should query any relationship between time-to-ON of oral levodopa doses to the timing of meals, protein intake and GI symptoms. Diagnostic testing for gastric emptying using nuclear scintigraphy can be helpful in some patients, but may be variable due to motor fluctuations, dyskinesia and PD medications.20

Management strategies for gastroparesis in patients with PD include a range of non-pharmacological approaches, such as taking multiple small meals, a low-fat diet and a reduction in the intake of indigestible fibre. Medications that can slow gastric emptying should be avoided if possible.

Pharmacological treatment of gastroparesis includes the use of prokinetic agents. Motilin agonists, such as the antibiotic erythromycin,32improve GI motility and gastric emptying, but tachyphylaxis develops within weeks, thus limiting their usefulness. Dopamine antagonists, such as domperidone and metoclopramide, can also improve gastric emptying due to gastroparesis. Metoclopramide, however, cannot be used by patients with PD, as it crosses the blood–brain barrier and will invariably worsen PD motor symptoms.22 Domperidone does not cross the blood–brain barrier so has only peripheral effects, and can improve gastric emptying in patients with PD without affecting PD motor symptoms.4,22 Injection of botulinum toxin into the pylorus,33–35 and gastric electrical stimulation have also been tried with variable results.36,37

In patients with PD, approaches to improve delayed ON and morning akinesia due to gastroparesis are limited. Dissolving oral levodopa into solution should allow it to empty sooner with the liquid phase of gastric emptying, but the duration of effect may be shorter. Dosing oral levodopa within 30 minutes of a meal may be helpful.3 Oral levodopa taken with a carbonated beverage may help stimulate gastric emptying. Higher or more frequent oral levodopa doses, orally dissolving levodopa or dispersible levodopa formulations have not been consistent.38–40 The use of adjunctive MAO inhibitors and long-acting dopamine agonists has led to alleviation of the severity of morning akinesia OFF, but do not lead to an ON state.41–44

Subcutaneous Apomorphine Injection for Treatment of Morning Akinesia

Apomorphine is a potent dopamine receptor agonist that can be administered subcutaneously. Subcutaneous apomorphine has a rapid onset of action when used for OFF periods14,45,46 in patients with PD, thus improving PD motor symptoms. Since subcutaneous injections avoid the oral route, apomorphine injections may be helpful to treat morning akinesia since its time-to-ON should not be affected by delayed gastric emptying due to gastroparesis. The ongoing phase IV, multicentre, openlabel Apokyn for Motor IMProvement of Morning Akinesia Trial (AMIMPAKT) is investigating whether subcutaneous apomorphine injection on awakening can provide improvements in motor and non-motor symptoms in PD patients with morning akinesia. This study is seeking to recruit approximately 100 subjects across 12 centres in the US. The primary endpoint of AM-IMPAKT is a change from baseline in time to turn ON as recorded in a daily diary after replacing their usual morning dose of oral levodopa with subcutaneous apomorphine injection. The frequency of delayed gastric emptying in patients with morning akinesia is also being investigated in the trial. A sub-study will evaluate whether subcutaneous apomorphine injection can affect gastric emptying.

Conclusion

In patients with PD, motor and non-motor symptoms of morning akinesia can be severely debilitating and have a significant effect on their QoL and daily activities. Gastroparesis is a common but underrecognised non-motor symptom of PD, which can also influence the effectiveness of oral levodopa, resulting in delayed onset of action.

The findings from AM-IMPAKT will be important in determining whether subcutaneous apomorphine injections can improve timeto-ON in patients with morning akinesia. This study will also provide further insights into the role of gastroparesis on morning akinesia, and whether apomorphine can affect gastroparesis, a common yet often under-recognised non-motor symptom of PD.