One of the elements in quality of life (QoL) in Parkinson’s disease (PD) is keeping the patients in an on state. However, there is more to QoL than simply keeping patients on: a growing body of literature exists that examines the elements that most affect QoL in PD.

One common conclusion was that the general health perceptions, health satisfaction and overall health-related QoL of PD patients are most closely correlated to psychosocial status (including educational, behavioural and psychological elements) as opposed to severity of physical symptoms.1,2 Depression and cognitive impairment are specifically associated with poor QoL. This should not be taken to mean that motor function is unimportant in improving QoL, but rather that the relationship between motor function and QoL must be viewed in a wider context.

Levodopa-induced non-motor complications, which can include nausea, hallucinations, insomnia and fatigue, certainly have a significant impact on physical functioning, but emotional wellbeing is affected as well.3–5 Furthermore, motor fluctuations and dyskinesias may be embarrassing and interfere with activities of daily living (ADL), hence also reducing QoL.6 Motor state and mood may even fluctuate in unison, often with severe feelings of depression, anxiety and hopelessness emerging with every off episode, to be replaced by feelings of euphoria and even symptoms of mania in the dyskinetic state. Therefore, keeping patients ‘on’ and avoiding motor fluctuations are indeed important component sof QoL. Assessing Quality of Life ?

There are a number of instruments available to assess QoL, although as yet none is ideal. Commonly used instruments include the Universal Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), which is well known and understood: part I concerns mentation, part II concerns ADL and part IV covers therapeutic complications. There is also the PD Questionnaire – 39 items (PDQ-39), which is sub-divided into physical, emotional and cognitive aspects of daily life. Other measures include recording on/off time, although on time itself can vary in quality: for example, it would be poor quality on time if the patient also suffered from dyskinesia.

Levodopa Oral Therapy

Levodopa is the most potent antiparkinson drug available, and generally is associated with only a few, well-tolerated side effects. After a ‘honeymoon’ period of excellent clinical response to levodopa therapy, which can last for three to five years, the duration of effect of each individual dose of levodopa slowly begins to shorten. The majority of patients treated long-term (for more than six years) with levodopa will eventually develop a fluctuating motor response to dosing. To begin with these fluctuations are small, but they become more complex and unpredictable over time.7 As this happens, QoL diminishes significantly: the social events of patients are curtailed, they become more reliant on care-givers for assistance with ADLs and, eventually, they become more socially withdrawn and isolated. In a British study of 87 community-based patients treated with levodopa, 28% experienced dyskinesias and 40% showed motor fluctuations. Motor fluctuations were most strongly related to disease duration and levodopa dose, whereas dyskinesias were best predicted by duration of levodopa therapy.8

Long-term levodopa use also causes non-motor complications such as sensory and behavioural disturbances, which contribute greatly to a patient’s perception of his or her QoL.5 Sensory complaints include numbness, which can occur before motor manifestations, and olfactory dysfunction. Patients can also experience feelings of dysphoria, which are characterised by anxiety, depression or unease. The anxiety, in turn, can lead to akathisia – an inability to sit still. The depression experienced by PD patients may differ from idiopathic depression in that it is not associated with feelings of guilt or failure.9

The frequency of non-motor symptoms in PD patients with motor fluctuations was assessed in a prospective assessment of 50 patients.10 Non-motor symptoms were grouped into three categories: sensory/pain symptoms, such as tingling, akathisia, a ‘tightening’ sensation or diffuse pain; mental disorders (cognitive/psychiatric), including anxiety, depression, fatigue, slow thinking, irritability or hallucinations; and autonomic dysfunction, for example drenching sweats, dyspnoea, facial flushing, dysphagia, dry mouth and constipation. All patients reported having experienced at least one form of non-motor fluctuation. Most also reported experiencing combinations of non-motor fluctuations belonging to two or more categories. Most common were anxiety (66%), drenching sweats (64%), slowness of thinking (58%), fatigue (56%), akathisia (54%) and irritability (52%). The total number of non-motor fluctuation symptoms in any given patient correlated with the degree of motor disability and severity of disease. Twenty-eight per cent of patients felt that non-motor fluctuations were more disabling than fluctuating motor symptoms.

Suspected Mechanism

As discussed in the first article, by José Obeso, the major pathophysiological mechanism underlying motor fluctuations is likely to be striatal denervation. Following degeneration of substantia nigra dopaminergic projections, striatal neurones lose the ability to store dopamine and regulate its release.11 In addition, pathological modification of striatal receptors, related to the non-physiological delivery of levodopa in a discontinuous pulsatile mode, may be partly responsible.11,12 Early onset of PD (at under 40 years of age) is also associated with more frequent appearance of motor fluctuations,13 as is receiving higher doses of levodopa.14 As the disease progresses, patient response to levodopa doses may be delayed. These delayed ‘on’ responses may be related to inadequate dose or delayed gastric emptying. This problem can be helped by increasing the levodopa dose; however, as already indicated, owing to the narrow therapeutic window in advanced patients higher doses may also induce dyskinesias.12 There are therapeutic alternatives and additions to levodopa, including anticholinergics, dopamine agonists, monoamine oxidase type B (MAO-B) inhibitors, catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitors and antiglutaminergic agents. However, as long as levodopa is a significant part of the treatment plan, these issues will remain.

Levodopa Infusion Considerations

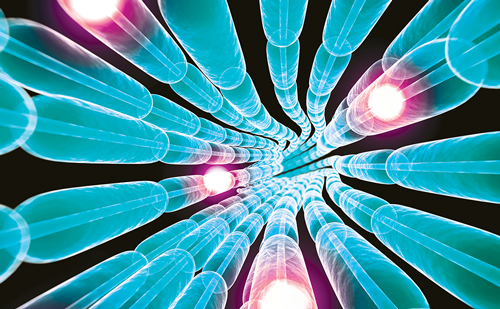

There is no gastric absorption of levodopa,15 hence erratic or delayed gastric emptying – which is a common feature in PD – will affect its transit to the duodenum and into the central nervous system when taken orally. Furthermore, there is an observable correlation between erratic gastric emptying and the wearing-off and missed ‘on’ phenomena.16 Thus, it is necessary to bypass the stomach in order to achieve stable serum concentrations. The first attempts to employ intravenous (IV) infusions of levodopa did produce stable serum concentrations without fluctuations. However, the main drawbacks were that levodopa is not very soluble in saline and needs to be kept at a low pH to remain in solution, making it impractical for an IV pump.17,18

One of the early studies to investigate the practicality of intraduodenal infusions of levodopa/carbidopa gel was undertaken by Bredberg et al., who examined the difference in levodopa plasma concentration in individual patients when given first oral levodopa/carbidopa and second an intraduodenal infusion of levodopa/carbidopa gel. The first scenario resulted in an erratic plasma levodopa concentration profile across two days, while the latter gave very little variance in serum levels.19

Overall, in the literature there is good evidence that intraduodenal levodopa achieves plasma concentrations with a coefficient of variance (CV) similar to continuous intravenous infusion (10–15%).18–20 In contrast, the CV for oral administration and gastric infusion is significantly higher (34–80+%). The development of a micronised suspension gel that allows higher concentration of levodopa per volume has made possible a convenient, portable delivery system. While the portable pump currently employed for this treatment may not be as small as an insulin pump, for example, it is nonetheless quite portable (it can be worn on the belt or with a shoulder strap), and as technology continues to progress the size will shrink.

Clinical Experience

So far, there have been slightly more than 20 published trials, including 200+ patients, evaluating intraduodenal levodopa infusion for advanced PD. Achievement of stable serum levodopa concentrations is well demonstrated, and the data would suggest that the degree of benefit is at least similar to that seen with deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus (STN-DBS). However, only a tiny proportion of these trials are blinded, randomised controlled trials.

The Duodopa Infusion: Randomized Efficacy and Quality of Life Trial (DIREQT) is one of a few that looked specifically at QoL. It enrolled 20 advanced PD patients already taking an optimised regimen of different drugs. It was a six-week randomised cross-over trial of oral polypharmacy versus infusion monotherapy. The primary end-points were a decrease in off time and an increase in functional on time. Results showed that off time fell from 19.2% of time on oral therapy to 1.8% during infusion, with a corresponding rise in functional on time from 74.5 to 90.7%. Patients reported that ease of walking, ADL, off time and overall satisfaction with their level of functioning were all significantly improved with infusion over oral therapy.21 Beyond the six weeks, the Uppsala team reported on nine cases of daytime levodopa infusion at six months, with a 31-month follow-up in two patients. They found that UPDRS parts I, II and IV improved over baseline, and that seven of the nine patients – including the two longest-term patients – maintained their improvement in mentation and ADL scores throughout their follow-up. Furthermore, eight of the patients showed maintained improvement in therapeutic complication scores over baseline.22 A recent publication by Antonini et al. reported follow-up experience of 22 advanced PD patients with troublesome motor complications. The researchers assessed improvement in off time, dyskinesia severity, ADL ratings and PDQ-39 with levodopa infusion over baseline. At twoyear follow-up all patients were found to have maintained significant improvement in all areas.23

While most studies have investigated daytime infusion, there is interest in 24-hour infusion, as many patients have troublesome and often debilitating night-time akinesia and sleep disturbances. Nyholm et al. investigated continuous levodopa infusion in five advanced PD patients, and found that all reported substantial improvement in akinesia and sleep quality with the 24-hour regimen. This benefit was maintained for the full 13–27 months of the study. Furthermore, the regimen was well tolerated and levodopa consumption remained stable.21

Summary and Conclusions

Motor complications are a primary cause of decline in QoL in advanced PD. Discontinuous levodopa delivery contributes to the development of motor and non-motor complications, and levodopa infusion provides stable continuous delivery. Clinical experience with levodopa infusion is encouraging. Further investigation is needed to more clearly assess the extent of the potential role of infusion in addressing this area of need.