Eventually the shortened and unstable motor response becomes unpredictable with no apparent relation to the timing of levodopa intake.This is known as the ‘on-off ’ phenomenon.1-4 The clinical syndrome is complicated further with the emergence of involuntary movements that are often choreiform but sometimes dystonic in nature. The significance of these motor response complications lies in the fact that they 1) affect the majority of patients with Parkinson’s disease treated chronically with levodopa, 2) represent a major source of disability in many patients rivalling that caused by the underlying disease itself, and 3) are the commonest reason for surgical intervention in Parkinson’s disease.

Causes for the Unstable Motor Response to Levodopa

Both peripheral pharmacokinetic factors and central pharmacodynamic changes contribute to the unstable response to levodopa.6 The short plasma half-life of levodopa of around 90 minutes is a clear limitation necessitating frequent dosing in advanced cases in order to maintain therapeutic blood and brain levels.7 Absorption of levodopa takes place primarily in the duodenum and is influenced by erratic gastric emptying and food boluses.8 Competition with dietary large neutral amino acids for entry across the blood–brain barrier can interfere with the access of levodopa to its site of action.9

While these peripheral pharmacokinetic factors are no different in the early versus the advanced disease, they assume clinical relevance only in advanced patients because of the fundamental central changes that occur in the brain in late stages of the disease.The fluctuating plasma levodopa levels go un-noticed in early disease because of the wide therapeutic window for this drug between its therapeutic anti-parkinsonian effect and the ‘toxic’ dyskinesias. As the disease progresses, the therapeutic window narrows significantly, allowing the fluctuations to become clinically apparent.10,11 When circulating levodopa levels fall below a certain threshold, parkinsonian symptoms re-emerge, but when the drug levels exceed the upper limit of the therapeutic window dyskinesias dominate. Only during the brief periods when the drug levels are within the narrow therapeutic window patients are mobile with no dyskinesias. Besides the narrowing of the therapeutic window, the dose response curve for the motor effects of levodopa within the therapeutic dose range changes from a relatively linear curve with a small slope in early disease to an S-shaped curve encompassing a virtually vertical slope.12 Small oscillations in plasma levodopa levels are translated to marked changes in the clinical response, sending the patient to abrupt and unpredictable shifts between bradykinetic ‘off ’ states and dyskinetic ‘on’ states. One of the central prerequisites for the unstable motor response to levodopa is severe nigrostriatal denervation in advanced disease. Clinical experience has shown that levodopa given to non-parkinsonian patients produces no dyskinesias in the absence of nigral neuronal degeneration. Twelve MPTP lesioned monkeys with upwards of 95% loss of dopamine neurons develop dyskinesias within days of starting levodopa therapy,13,14 whereas partially lesioned animals are much more resistant to the development of levodopa induced dyskinesias.15,16 With advancing Parkinson’s disease, as the number of dopamine producing nigral neurons decrease from about 50% at the onset of symptoms down to about 20% or less, striatal dopaminoceptive medium spiny neurons become increasingly exposed to the fluctuations in plasma and brain levels of levodopa and hence dopamine. The presence of a normal complement of nigral dopaminergic neurons in non-parkinsonian individuals shields the striatum from oscillating levodopa levels.Additionally, individuals who have developed severe subacute Parkinsonism as a result of accidental exposure to the dopaminergic neurotoxin MPTP have massive nigrostriatal degeneration and manifest levodopa induced motor response fluctuations and dyskinesias within months of starting therapy.17 Patients with Parkinson’s disease due to mutations in the parkin gene and severe neuronal loss also develop dyskinesias early on.18

Finally, several prospective, double-blind controlled studies have compared the time to onset of motor response complications in untreated patients randomized to initiate therapy with either standard oral levodopa or relatively longer acting dopamine agonists.19-22 While dopamine agonist therapy perse is associated with less dyskinesias, those who start with a dopamine agonist first and then switch to levodopa develop fluctuations at about the same time as those who start levodopa from the outset. The latter finding suggests that the duration of disease, and by implication the degree of neuronal loss, is an important element in the genesis of motor complications.

Experimental observations suggest that the second prerequisite for the development of motor fluctuations in PD is long-term intermittent levodopa administration. In monkeys rendered parkinsonian by MPTP, repeated dosing with oral levodopa produces dyskinetic movements, while treatment with a long acting dopamine agonist is associated with considerably less or no dyskinesias.13,14,23 While such an observation may be attributed simply to the lesser tendency of dopamine agonists than levodopa to induce dyskinesias, studies comparing the same dopaminomimetic agent given in different treatment schedules have yielded similar results.24 Parkinsonian monkeys develop involuntary movements if apomorphine is injected daily but not if the same drug is delivered at the same dose level through an implant releasing apomorphine continuously.25 Similarly, 6-hydroxydopamine lesioned rats injected twice daily with levodopa rotate much more that those in which levodopa is infused continuously through a pump.26 Over time, such intermittently treated mice develop the clinical equivalent of ‘wearing-off ’ phenomenon with reduced duration of motor effects of levodopa,26,27 a phenomenon which is dependent on the severity of dopamine neurons loss.28 Pathophysiological Changes with Advancing Parkinson’s Disease and Intermittent Levodopa Therapy

Support for the notion that continuous dopaminergic stimulation is superior to intermittent therapy stems from the fact that, under normal conditions, dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta fire tonically at a steady slow rate of about four hertz regardless if the animal is at rest or moving. Striatal dopamine concentrations are stable as well.29,30 With the anticipation of reward or novel stimuli,31 dopamine neurons can fire in bursts, but the efficient reuptake by dopamine transporters allows the maintenance of intrasynaptic dopamine concentrations to be fairly steady. In early PD,when half the dopaminergic neurons are still intact, dopamine can be synthesized and stored in slowly turning over vesicles, only to be released tonically, thus shielding the postsynaptic dopamine receptors from oscillations in circulating levodopa levels. With advancing disease as more and more neurons disappear and the capacity to store dopamine and release it tonically is diminished, standard intermittent oral therapy with anti-parkinsonian agents with a relatively short half-life, such as levodopa, result in oscillations in striatal intrasynaptic dopamine levels that mirror the oscillations in plasma.32 A neurotransmitter system that is designed to function normally tonically is replaced with an artificially pulsatile system. This non-physiologic situation is believed to underlie the altered pharmacodynamics of the levodopa response.

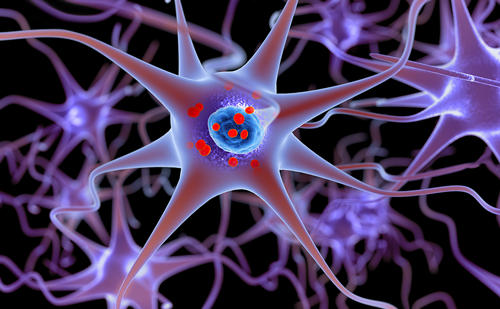

Biochemical and molecular aberrations have been documented in experimental models as a result of intermittent stimulation of the nigrostriatal dopaminergic system. Repeated administration of short acting dopaminomimetics in rodent and non-human primate models of PD associated with dyskinesias result in altered expression of various peptide transmitters and signaling molecules including enkephalin, dynorphin, neurotensin, Fos and JunB proteins, ERK1/DARP,32 and D1 signaling molecules.33-38 Some of these changes have also been detected in post-mortem brain tissue of PD patients including substantially elevated preproenkephalin in patients who had levodopa induced dyskineisas compared with patients treated with levodopa but did not manifest dyskinesias or to normal control individuals.39 In MPTP monkeys treated with a D2 dopamine agonist, neither the enkephalin changes nor dyskinesias seen with intermittent therapy occur if the drug is given continuously.35 Dopamine receptor mediated mechanisms modulate the sensitivity of ionotropic glutamatergic receptors of the NMDA and AMPA types on striatal medium spiny neurons.With dopaminergic denervation, and to a greater extent with intermittent dopaminergic therapy, the sensitivity of these glutamate receptors is increased.40,41 Changes in the phosphorylation state of certain sub-units of these glutamate receptors enhance cortical excitatory input to these spiny efferent neurons, thus altering striatal output in ways that compromise motor function. These transmitter modifications reflect increases in the firing rates and other burst parameters of medium spiny neurons that appear to underlie changes in motor behavior. 42Advantages of Continuous Dopaminergic Stimulation

The merits of continuous dopaminergic stimulation have been amply demonstrated in stabilizing the motor fluctuation in patients with advanced PD.43-45 This has been shown both with levodopa and dopamine agonists. Levodopa infused continuously intravenously or intraduodenally markedly reduces oscillations in plasma drug levels and ‘wearing-off ’ fluctuations and dyskinesias.46-48 Dopamine agonists have similar properties when delivered continuously, such as lisuride and apomorphine infused subcutaneously, or rotigotine transdermally.49, 50-53

While the question whether continuous antiparkinsonian therapy postpones or minimizes future genesis of fluctuations and dyskinesias has been convincingly demonstrated in primate and rodent models as described above, proving the same notion in the clinical setting has been more challenging. In a prospective study,40 levodopa-treated Parkinson patients experiencing severe ‘off ’ times and dyskinesias were randomized to either continue receiving intermittent oral levodopa or to switch to a continuous subcutaneous infusion of lisuride.54 As expected, the lisuride infusion group showed marked improvement in ‘off ’ times and dyskinesias compared with the oral levodopa group. After a period of four years, ‘off ’ time had improved by around 71% in the infusion group and worsened by 21% in the oral levodopa group. Dyskinesias were reduced by 49% in patients infused with lisuride but increased by 59% in patients given oral levodopa. These encouraging observations support the notion that long-term continuous dopaminergic stimulation minimizes motor response complications.

The plasticity of the basal ganglia circuitry that underlie the central pharmacodynamic changes associated with long term intermittent dopaminergic stimulation also appears to be reversible, at least to some extent. Motor fluctuations of the unpredictable ‘on-off ’ type that tend to be quite resistant initially even to continuous dopaminomimetic therapy are eventually ameliorated with persistent drug delivery such as with intravenous infusion of levodopa.

Abruptly switching back to intermittent therapy does not revert the patients to their baseline severity of motor fluctuations. Rather, a relatively smooth motor response is enjoyed for at least several more days until the beneficial effect of continuous therapy eventually dissipates.46 The latter observation suggests that continuous therapy had produced plastic changes in the basal ganglia, which lasted well beyond the removal of the physiologic stimulation and re-introduction of intermittent therapy. The advantages of continuous dopaminergic therapy in Parkinson’s disease can be gained in both early and advanced disease where fluctuations can be ameliorated both by stabilizing circulating drug levels and by normalizing some of the central pharmacodynamic alterations attending chronic non-physiologic intermittent stimulation.

Acknowledgement

The author acknowledges the support of the William Dow Lovett Endowment.