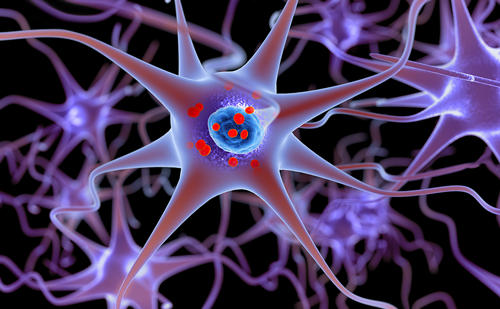

The management of the later stages of Parkinson’s disease (PD) is greatly impacted by non-dopaminergic problems, such as dementia, depression and falls, and by the emergence of motor complications including motor fluctuations and dyskinesias. Motor fluctuations, such as ‘wearing off’ and unpredictable ‘off’, affect 30–100 % of patients.1–4 Dyskinesias can be ‘on’ (mostly choreatic), biphasic (often dystonic) or ‘off’ (dystonic). In the later stages of the disease, there is a loss of nigrostriatal neurons and a concomitant loss of storage capacity. Positron emission tomography imaging of dyskinetic and non-dyskinetic patients showed no difference in dopamine receptor binding, which suggests that dyskinesias are unlikely to be the effect of alterations in striatal dopamine receptor binding.5 On the other hand, levodopa-induced changes in synaptic dopamine levels increase with the progression of PD.6 These changes in synaptic dopamine concentration may be a factor in the emergence of peak-dose dyskinesias.

The pharmacokinetics of levodopa in the periphery, such as plasma half-life clearance, volume of distribution and maximum plasma concentrations, remain unchanged.7 However, the absorption f oral levodopa, which takes place primarily in the duodenum, is affected as gastric emptying becomes more erratic.8,9 Pharmacodynamic postsynaptic striatal changes in gene expression,10 neuropeptide formation11 and discharge patterns of the basal ganglia12 result in complex feedback loops.13 Furthermore, non-dopaminergic factors such as glutamate, opioids and serotoninmay be involved in the development of dyskinesia.14 Sprouting of extrasynaptic dopaminergic terminals may also lead to dysregulateddopamine release.15

One of the most important factors associated with the risk of motor complications is the degree of neuronal loss. In rats whose nigrostriatal system had been lesioned unilaterally by 6-hydroxydopamine, the level of levodopa-induced motor complications was related to lesion size.16 In humans, if the first dose of levodopa is given at an advanced stage of the disease, motor complications may develop within a matter of weeks.17 Furthermore, patients with 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6- tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-induced chronic and severe parkinsonism developed dyskinesias or ‘on-off’ fluctuations within months of starting levodopa treatment.14 Additional factors that contribute to a greater risk of motor complications include younger age at disease onset,3,18 lower bodyweight19,20 and genetic factors.21

To view the full article in PDF or eBook formats, please click on the icons above.