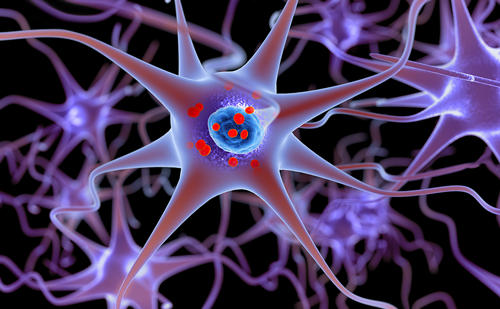

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder, with an average age of onset of 56, that causes abnormalities both in motor and non-motor functioning. Clinical features that affect motor function include bradykinesia, rigidity, resting tremor, gait abnormality, and postural instability. Clinical features that affect non-motor function include cognitive dysfunction, depression, anxiety, sleep disorders, orthostatic hypotension, urinary dysfunction, and constipation. There are recognized differences in prevalence and clinical manifestations of PD between ethnicities. The reasons behind these differences, however, are unclear. Is it because of differences in the clinical care that minority populations are able to access? Or are there biological differences in PD that have not been fully explored? Or is it a combination of both? There has been a paucity of PD research related to non-Caucasian populations which limits our ability to answer these questions.

On May 17, 2019, the American Parkinson Disease Association (APDA) convened the first-ever Diversity in Parkinson’s Disease Research Conference to address the unique and urgent needs surrounding PD in diverse and under-served communities. With the support of a grant from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), APDA gathered experts to present the current data concerning PD in diverse populations and to spur conversation amongst participants of ways to further our understanding of PD in these populations. The conference brought together researchers, clinicians, people with PD, care partners, patient advocates, nurses, research coordinators, and social workers. Conference participants, representing 15 US states, came from academic medicine, community hospitals, pharmaceutical companies, the Veterans Administration, and patient advocacy groups. Speakers presented lectures on the health disparities and biological differences amongst diverse PD populations. Topics included disparities in natural history, clinical care and outcomes in diverse PD populations, disparities in PD clinical trial enrollment, and genetics of PD in diverse populations.

Disparities in natural history, clinical care, and outcomes in diverse Parkinson’s disease populations within the United States

There are documented discrepancies in the natural history, clinical care, and outcomes received by patients of varying ethnicities within the United States.

- Incidence and prevalence of PD are not consistent across all ethnicities. Studies have shown that African Americans and Asian Americans have lower incidence and prevalence than the general population.1–4 Interestingly, the difference between prevalence is more notable than the difference between incidence, which may imply that the disease course is shorter and possibly more aggressive in this population.3 One door-to-door study, however, did not show a difference in prevalence between ethnicities.5

- A study that looked at national data across a wide range of neurologic conditions, demonstrated that black participants in the study were 30% less likely to see an outpatient neurologist as compared with white participants. Hispanic participants were 40% less likely to see an outpatient neurologist. Black participants were also more likely to be cared for in the emergency department and to have more hospital stays.6 These trends held true for patients with PD as well.7

- African Americans with PD had lower utilization of outpatient rehabilitation services such as physical and occupational therapy.8

- In a study at a tertiary Movement Disorders Center, African Americans showed greater disability and disease severity as compared with white patients and were less likely to be prescribed dopaminergic medications, particularly newer agents.9

- In another study, African Americans were four times less likely than whites to receive any PD treatment, even controlling for healthcare insurance.10

- There is evidence that African Americans present to medical attention at a later stage than whites and are more likely to under-report disability as compared to actual motor impairment.11

- African Americans are referred to deep brain stimulation (DBS) surgery at lower rates than Caucasians.12,13

The conference laid out a blueprint of how to overcome these challenges, based on a paper by Kilbourne, et al14 First the disparities must be detected and measured, then the reasons for the disparities must be understood, and finally programs must be implemented to reduce the disparities. A good example for analysis is the healthcare disparity of varying rates of DBS referral. Once research has detected that this disparity exists, further research must now be aimed to understand why this disparity exists. Is it because the clinical characteristics of African American patients are different than Caucasians and are less likely to be good DBS candidates? Is physician bias playing a role? Are African American patients referred for surgery but are less willing to undergo it? Once the research postulates the reason(s) behind the disparity, then programs can be implemented to address the issue and ensure that all people with PD have access to the treatments that are best for them.

Disparities in Parkinson’s disease clinical trial enrollment

The fact that racial and ethnic minorities are under-represented in clinical trials is pervasive across medical disciplines and is a major barrier to investigations of what underlies differences in PD between populations. A study of the under-representation of minorities specifically in PD clinical trials demonstrated that (among the trials that reported ethnicity), 8% of the subjects were non-white, whereas 20% of the population in the US over the age of 60 is non-white.15

There is extensive literature analyzing the barriers to clinical trial enrollment, which include patient mistrust of medical researchers and medical institutions, lack of minority investigators with whom to foster trust, lack of access to specialty care, expectation of negative outcomes, fear of being “experimented upon”, lack of independence to manage travel and time associated with a clinical trial, lack of knowledge about clinical trials, social norms and opinions discouraging clinical trials, and lack of health literacy concerning clinical trial basics. In addition, minority-serving community physicians demonstrate distrust of the medical institutions conducting research and are therefore reluctant to refer their patients for studies.16 A model to counteract some of these forces involves building trust between research institutions and minority-serving community physicians.

Some potential solutions to the problem of disparities in clinical trial enrollment in diverse populations, were described at the Diversity in Parkinson’s Disease Research Conference. An example of a program that has had success in increasing minority participation in research in the field of cancer research, and could be implemented for PD clinical trials, is the use of patient navigators (professionals trained to support people throughout the clinical trial process).17 Other suggestions made at the conference to improve clinical trial participation in under-represented populations were the writing of recruitment letters to potential trial participants to explain the need for people from minority communities to enroll, and the use of community settings (e.g. Senior Centers) as research sites to make involvement in clinical trials more convenient and more accessible.

Overview of genetics in diverse Parkinson’s disease populations

About 15% of the PD population has a family history of the disease.18 Most of the patients with a family history do not harbor a known mutation, suggesting that many more mutations are yet to be discovered. In addition, the known mutations are likely to be responsible for the disease in some patients without a family history as well. Patients from ethnic minorities are not well represented in genetics trials, which leads to gaps in our knowledge about the genetics of these populations. The PD treatments of the future may very well be tailored to particular genetic mutations. If people receive personalized treatment depending on which genetic mutation they have, then it is essential that all populations are studied and our understanding of the genetics of PD is as complete as possible.

Another important element to consider is that each discovery of a new genetic mutation that causes PD opens up a window into our understanding of PD more generally. Therefore, the discovery of a genetic mutation in one population could have implications for the entire PD community. An overview of the Latin American Research Consortium on the Genetics of Parkinson’s disease (LARGE-PD) was presented at the Diversity in Parkinson’s Disease Research Conference. LARGE-PD is a multi-national effort to identify genes, specific to Latino populations, that play a role in PD.19 This effort is ongoing with the hope of increasing our knowledge concerning the genetics that contribute to PD in a variety of populations.

Hearing everyone’s contribution

An engaging “People with Parkinson’s Disease and Care Partner” panel was held at the Diversity in Parkinson’s Disease Research Conference, and brought the essential patient voice to the discussion. Participants in the panel, who had also been involved in planning the conference, addressed issues universally experienced by people with PD as well as unique concerns of Hispanic and African American people with PD. Researchers of health care disparities in the fields of multiple sclerosis and hypertension presented their successes with the hopes that their programs could be modified for use in the field of PD. Finally, a discussion among all the conference participants elicited ideas on how to better study health disparities and biological differences between diverse PD populations.

Conference gaps

Whereas the conference focused on issues of disparity most relevant in the United States, differences in prevalence, natural history, clinical care, outcomes and clinical features in diverse PD populations throughout the world is a larger topic of extreme importance. Research of PD communities across the world has been conducted (for example, in Korea,20 India,21 and Ethiopia22) but much more is necessary to fully understand the variability in the disease across populations. Even the question of difference in prevalence between worldwide communities is not fully understood. One meta-analysis determined that PD prevalence was lower in Asia than in North America, South America, and Australia.23 However, not all studies concur, with some showing similar prevalence of PD in rural China as in non-Asian countries.24 Similar to ethnic populations within the US, differences in PD features among worldwide populations can be attributed to a variety of factors outlined in a review on the subject,25 including life expectancy and length of survival with PD, comorbidities, diet, cultural differences, differences in clinical care, and genetics.

Conclusions

The Diversity in Parkinson’s Disease Research Conference established that current research has shown the following:

- There are substantial disparities in clinical care and outcomes in diverse PD populations

- Clinical trial enrollment among ethnic minorities is lower than in Caucasian patients

- Biological differences (including genetics, but also encompassing clinical features, response to treatment, co-morbidities, prevalence, natural history, genetics, biomarkers) between minorities have not been fully explored.

Building off of these principles, participants formulated research study ideas that would detect and measure these disparities or differences, understand the reasons behind these disparities or differences, and/or test interventions to improve disparities. APDA is turning the challenges identified at the conference into the basis for a specific grant that will be awarded to support research that is focused on closing the diversity gaps.