Infection of the central nervous system (CNS) due to cytomegalovirus (CMV) is rare, as it typically occurrs in immunocompromised patients and rarely affects those who are immunocompetent.1 Brain infection – manifested by meningoencephalitis – is much more common than infection of the spinal cord or nerve roots.1 CMV infection of the spine has been almost exclusively reported as an inflammatory polyradiculitis of the spinal nerve roots in immunocompromised patients, particularly those with HIV/AIDS.1,2 In this paper, we present an unusual case of severe encephalomyelitis and polyradiculitis in an immunocompetent woman. This case report describes an uncommon presentation of CMV encephalomyelitis and polyradiculitis and adds to the limited data on its diagnosis, treatment and prognosis in immunocompetent patients. Verbal consent was obtained from the patient herself. Consent was given verbally because the patient was unable to use her hands to sign the consent due to weakness.

Case report

A 41-year-old African-American woman with diabetes mellitus and hypertension presented to the hospital with general fatigue, dizziness and low-grade fever after 1 month of upper respiratory tract infection and bilateral conjunctivitis. Over the next few days, she experienced bilateral lower extremity weakness, urinary retention and diplopia. An external ocular exam showed scattered corneal sub-epithelial infiltrates with absent anterior segment inflammation and normal dilated fundus exam. Ocular motility showed a bilateral restriction of upward gaze, limited right lateral gaze and bilateral partial ptosis. The rest of the cranial nerves examination was normal. Strength was Medical Research Council grade 0/5 in the lower extremities and 4/5 in the upper extremities. Reflexes were 0/4 in the lower extremities and 1/4 in the upper extremities. A sensory exam showed hypo-esthesia, with a sensory level at T4. One day later, the patient had complete external ophthalmoplegia, complete ptosis, weakness of upper extremities with 0/5 strength and absent reflexes. She became lethargic and unable to protect her airways, necessitating emergency intubation and mechanical ventilation.

Workup

The patient’s initial laboratory workup was unremarkable, except for an elevated serum CMV immunoglobulin (Ig) M level of >240 AU/mL (reference 29.9 AU/mL) and IgG level of 3.6 μg/mL (reference >0.7 μg/mL). A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, orbit and spine with and without contrast showed extensive T2 hyper-intensities, T1 enhancement and oedema along the entire length of the thoracic and cervical spine. She underwent lumbar puncture on admission, and her cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) showed a protein level of 73 mg/dL (reference 15–45 mg/dL), a glucose level of 44 mg/dL (reference 41–70 mg/dL), 44 nucleated cells (88% of which were lymphocytes; reference 0–5 cells/µL) and positive CMV DNA detected using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Lumbar puncture was repeated 1 week after admission, and the CSF continued to show CMV DNA using PCR.

To rule out other aetiologies, the patient underwent an extensive infection and autoimmune workup. Aside for CMV, the CSF meningitis/encephalitis panel was negative for all pathogensctested (this assay can detect Escherichia coli K1, Haemophilus influenzae, Listeria monocytogenes, Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Cryptococcus neoformans/gattii, CMV, enterovirus, human herpesvirus 6, Herpes simplex virus-1, herpes simplex virus-2, human parechovirus, and varicella zoster virus). The PCR of CSF was negative for syphillis, fungal infection and tuberculosis. Serum was negative for tick-borne diseases, Lyme disease, HIV and syphilis. Blood cultures showed no bacterial growth. Serum autoimmune workup was negative for anti–Sjögren’s-syndrome-related antigen A autoantibodies, anti-Sjögren’s syndrome type B, antibodies to ribonucleoprotein, anti-Smith antibody, anti-Scl-70 antibody, anti-chromatin antibody, anti-Jo 1 antibody, anti-centromere antibody, anti-double-stranded DNA antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, myeloperoxidase antibodies, anti-proteinase-3 and hypocomplementaemia. The patient’s C-reactive protein was elevated at 240.5 mg/L (reference ≤8.0 mg/L), and her serum was weakly positive for anti-nuclear antibody (1:160 homogenous pattern), rheumatoid factor and lupus anti-coagulant. Anti-aquaporin-4 antibodies and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibodies were negative on multiple tests. The patient’s CD4+ count was 255 cells/UL (reference 490–1,730 cells/UL).

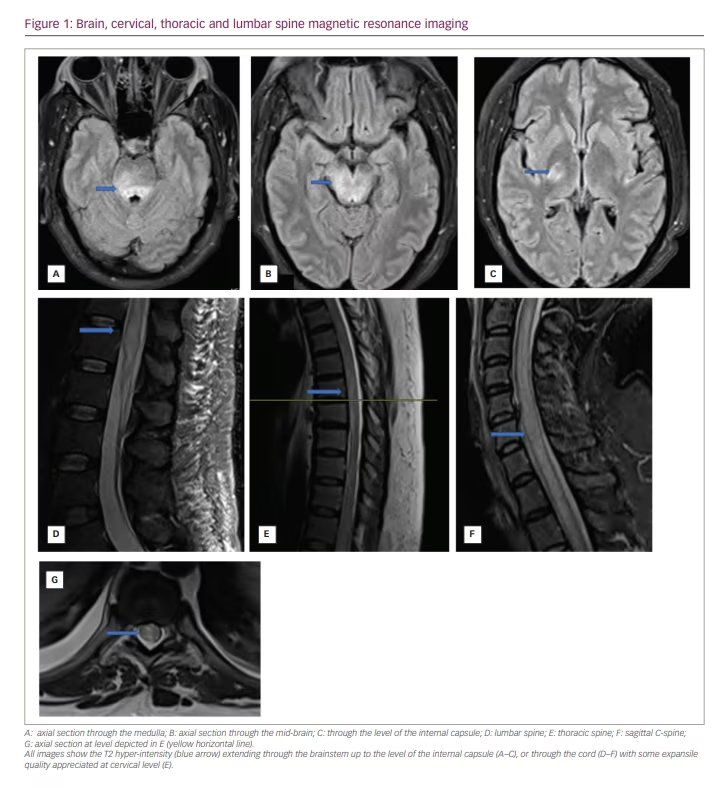

A nerve conduction study revealed severe length-dependent generalized axonal sensory-motor neuropathy. Contrasted chest computed tomography revealed right-sided hilar adenopathy, measuring up to 18 mm. A biopsy of the lymph nodes was unrevealing, showing non-specific inflammation. Brain and spine MRIs were repeated on day 7 following admission and showed a progression of the inflammation and oedema, now involving the brainstem throughout the midbrain and up to the internal capsule (Figure 1). The right anterior intraconal optic nerve was also enhanced.

Treatment

Since the patient’s CSF was positive for CMV DNA, she was started on intravenous (IV) ganciclovir on day 1 of admission, and IV foscarnet was added on day 2, as per infectious disease team recommendations. Because the initial diagnosis was uncertain, the patient was also started on IVIg for 5 days during her second week in the hospital. For the significant cord oedema, she was treated with IV dexamethasone for 5 days, with minimal improvement in her proximal arm strength and ocular motility. She continued IV antiviral medications for 15 days. Over the following month, her mental status improved significantly. Her eye movements were intact, and she was able to feel light touch in all extremities, with further improvement in shoulder movements. However, the rest of her motor exam continued to show 0/5 with areflexia.

Outcome

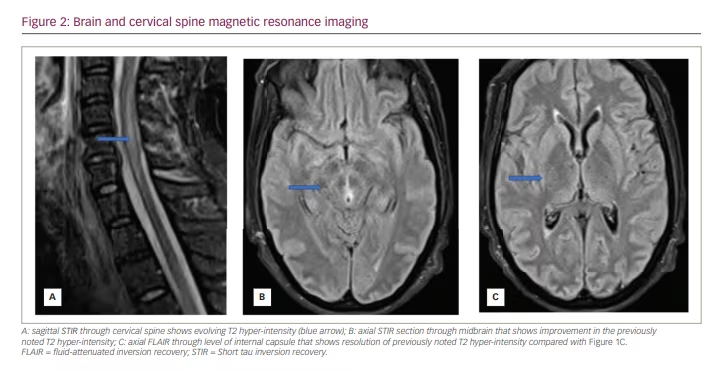

A repeat lumbar puncture after 2 weeks showed normal protein levels, no nucleated cells and CMV DNA undetectable by PCR. Brain and spine MRI repeated 10 days after the completion of the antiviral therapy showed no further progression of lesions, with signs of maturation of the presumed demyelinating lesions (Figure 2). The patient subsequently underwent tracheostomy and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement and was referred to a long-term care facility. While awaiting placement, she underwent brain and spinal MRI 3 months after her acute illness; this showed resolution of cord oedema, regression of previously noted lesions and no new lesions. Repeated HIV testing after 3 months was negative.

Discussion

CMV is a double-strand DNA virus belonging to the family Herpesviridae. CMV infection is widespread, and its manifestations range from being asymptomatic in the immunocompetent host to severe and life-threatening in immunocompromised patients.3 Primary CMV infection may present as an acute febrile illness resembling flu or may present with symptoms related to gastro-intestinal, lung, liver and central and peripheral nervous system involvement.3

This case report describes a patient who had conjunctivitis and flu-like illness 1 month prior to the onset of neurologic symptoms. Given the temporal relationship between infection and symptoms and the presence of serum CMV IgM at the time of neurologic symptoms, we believe that her upper respiratory illness may have represented an acute primary CMV infection.

CMV infection of the central and peripheral nervous system occurs mainly in patients who are immunocompromised, particularly those with HIV/AIDS.1,2 CNS involvement is rare and occurs in less than 1% of CMV infections in this group of immunocompromised patients.3 On the other hand, CMV-related neurologic infection in immunocompetent patients is very rare: very few cases have been reported in the literature.4–6 In a report of 676 patients with CMV encephalitis, 85% of the patients had HIV infection, 12% had other immunosuppression aetiologies, and only 3% were otherwise healthy.7 Our patient was immunocompetent, tested negative for HIV on multiple occasions during her hospital stay and was not on immunosuppressive medications.

In patients with AIDS, severe CMV infections have been reported in those with CD4+ counts lower than 502 cells/UL. The CD4+ count in our patient was of 255 cells/μL; while this is lower than the normal range, it is not however low enough for the patient to be considered at risk for severe CMV infection. On the other hand, this mildly depressed CD4+ count may be related to primary CMV infection.

Due to its rarity in immunocompetent patients, the diagnosis of CMV neuro-infection is complex and requires a high index of suspicion. The diagnosis in our patient was challenging simply because her extensive disease with the presence of acute bilateral external ophthalmoplegia was unique and exceedingly rare in the setting of CMV infection. She had a constellation of symptoms related to encephalitis, extensive transverse myelitis and polyradiculitis; to the best of the authors’ knowledge, these conditions have never been described together in the same patient.

Our patient’s initial differential diagnosis was broad; therefore, she underwent an extensive workup that included autoimmune and infectious aetiologies. Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disease and MOG antibody diseases were initially considered; however, both were eliminated with the exam findings of areflexia throughout her hospital course and the absence of serum anti-aquaporin-4 and anti-MOG antibodies on two separate occasions. In addition, her nerve conduction study showed axonal neuropathy, which is not a part of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disease. Guillain–Barré syndrome was also considered;8 however, the presence of optic nerve involvement, the absence of albumin cytologic dissociation on CSF analysis and the absence of the anti-GQ1B antibodies in our patient eliminated the diagnosis of Guillain–Barré syndrome. Sarcoidosis was also considered but was ruled out by a negative tissue biopsy and the rapid clinical progression.

In general, CMV neuro-infection is diagnosed based on clinical presentation and the presence of CMV in CSF or brain tissue. Antemortem, culturing CMV from brain tissues and CSF is difficult; instead, PCR allows CMV to be detected based on the presence of its DNA within the CSF, and has been found to be the most reliable method for diagnosing CMV-related CNS infection.9 In addition, previous studies have shown that the presence of CMV DNA in CSF detected in this way indicates infection rather than latency in acute CNS disease.10 Based on serum serology, PCR results of CSF CMV and the absence of strong evidence for an alternative diagnosis, we concluded that our patient’s acute illness was caused by CMV infection.

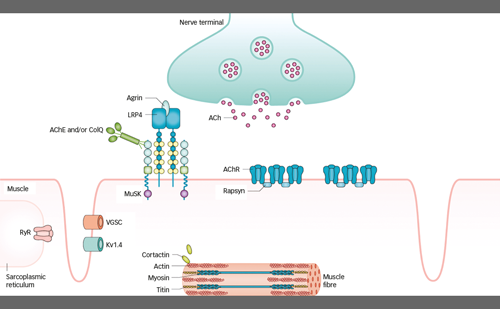

CNS manifestations of CMV infection include encephalitis, meningoencephalitis and myelitis with and without the involvement of the radices.1,2,9,11 Polyradiculomyelitis initially involves the lower extremities, with ascending areflexia, numbness and urinary retention. In some reported cases, the upper extremities and cranial nerves had been affected: this clinical syndrome has been reported in immunocompromised patients.1,2 The case we present here exhibited clinical and radiologic features of encephalitis and polyradiculomyelitis. She had extensive transverse myelitis involving the entire cervical and thoracic spine. The inflammation extended rostrally to involve the brain stem, internal capsule and optic nerve. She also had peripheral axonal neuropathy evident in the nerve conduction study.

Controlled and randomized trials in immunocompetent patients are lacking, so the optimal antiviral treatment for CMV infection has yet to be determined. In patients with AIDS and CMV neurological diseases, the International AIDS Society recommends IV ganciclovir and/or IV foscarnet.12 Some clinicians also recommend these agents to immunocompetent patients, too.10 On the other hand, some immunocompetent patients with CMV encephalitis achieve a favourable outcome without treatment.13 Our patient received a combination of ganciclovir and foscarnet for 15 days, as well as IV dexamethasone and IVIg for 5 days. She had a prolonged course and began improving only after almost 4 weeks of illness. It is unclear if her improvement was due to the treatments or simply the natural course of the disease in immunocompetent patients.

Conclusion

This case describes the severe life-threatening complications of CMV infection in an immunocompetent patient. Due to the rarity of this neuro-infectious syndrome in immunocompetent patients, no consensus exists on the use of antiviral treatment; thus, randomized controlled trials are needed. Until then, case reports with favourable outcomes may help guide clinical decisions in the absence of empirical data.