Migraine is the most common neurological disorder and one of the most disabling health disorders worldwide, often occurring in working age, and in young adult and middle-aged women.1 It is a debilitating condition that is hard to treat, can last anywhere from 4 hours to 3 days and has a substantial negative impact on quality of life.2 Some patients treat their migraine attacks with drugs to relieve pain but, in some patients, the frequency, severity and impact on quality of life necessitates the use of preventive treatment to reduce the occurrence of acute attacks. However, in contrast to acute treatment, there are no specific treatments for migraine prophylaxis to date. A number of drugs are available, but all have been developed for other conditions, such as hypertension, depression or epilepsy. Currently available preventive therapies are associated with low adherence rates due to lack of efficacy and/or poor tolerability.3

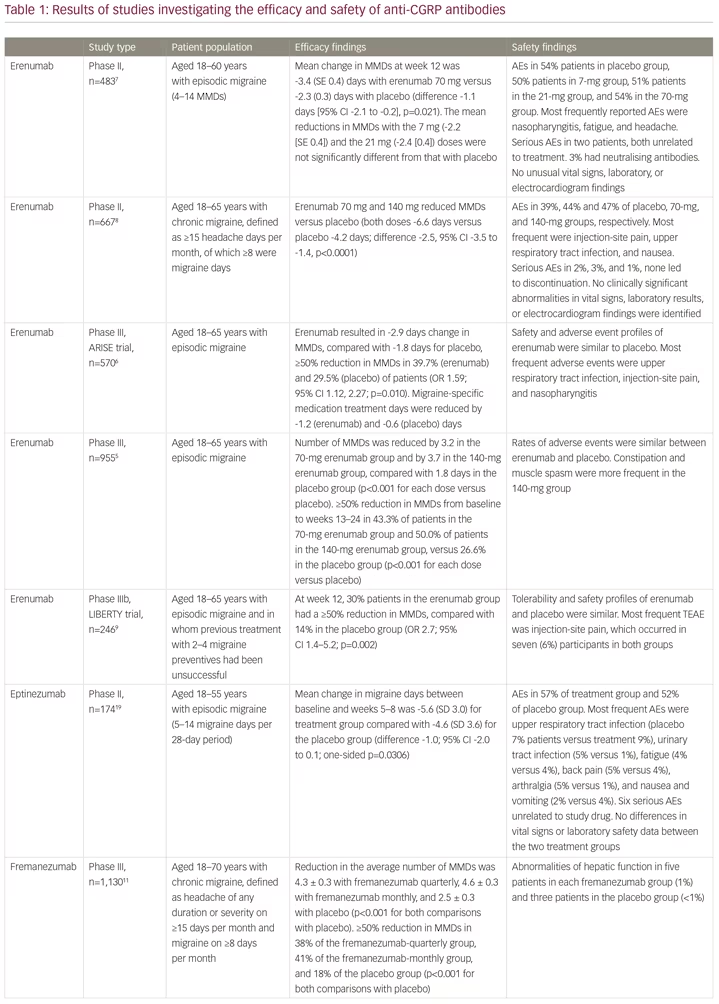

Erenumab (Aimovig®, Novartis Pharma GmbH, Nuremberg, Germany) is a first-in-class human monoclonal antibody to the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor, which is important in the pathophysiology of migraine.4 It is highly selective and has a high biological half-life, requiring monthly subcutaneous injection, and no drug titration. The clinical development of erenumab involved a number of clinical trials. A phase II study and two phase III studies showed efficacy and safety in patients with episodic migraine,5–7 and a randomised phase II trial showed efficacy and safety in patients with in chronic migraine (Table 1).8 The effective reduction of monthly headache or migraine days due to treatment could be observed very early, after less than 1 month from the first dose. The 12-week, double-blind, phase IIIb LIBERTY study aimed to answer the question of where to fit erenumab into the treatment paradigm.9 LIBERTY recruited patients who had failed 2–4 previous migraine therapies and were therefore considered difficult to treat. These represent the majority of migraine patients seen by neurologists in clinical practice, but who are often excluded from clinical studies.

A total of 246 patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to erenumab (140 mg, administered by subcutaneous injection) or placebo. At baseline, 39% of participants had previously unsuccessfully tried two preventive drugs, 93 (38%) had tried three, and 56 (23%) had tried four. The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients achieving a reduction of at least 50% from baseline in monthly migraine days (MMDs) during weeks 9–12. At week 12, the proportion of patients achieving a reduction of at least 50% in MMDs in the erenumab group was almost three times that in the placebo group (30.3% versus 13.7%; odds ratio [OR] 2.7; p=0.002). A larger proportion of patients in the active treatment group than in the placebo group achieved a ≥75% rate (11.8% versus 4.0%; OR 3.2). A 100% response rate was seen in 5.9% of the treatment group compared with none in the placebo group. The safety and tolerability of erenumab were comparable to placebo. The safety profiles of erenumab and placebo were similar. The most frequent treatment-emergent adverse event was injection-site pain, which occurred in seven (6%) participants in both groups.9 The tolerability of erenumab is good, which is reflected by low dropout rates in all erenumab clinical trials. As a result of these findings, erenumab received approval from the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in May 2019.

The implications of these findings are important for clinical practice as, for the first time, clinicians and patients have the option of a drug based on the pathophysiology of migraine. Erenumab shows a low risk for drug–drug interactions and hepatotoxicity since it is metabolised by degradation into peptides and single amino acids,10 an important consideration for patients using multiple medications.

Since the approval of erenumab, two other anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies, fremanezumab (Ajovy®, Teva, Petah Tikva, Israel)11–13 and galcanezumab (Emgality™, Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN, USA),14–18 have received European Medicines Agency approval for migraine prevention, with a fourth agent, eptinezumab, in clinical development (Table 1).19 The most important difference between the drugs is that fremanezumab, galcanezumab and eptinezumab target the CGRP protein, while erenumab targets the canonical receptor. The implications of this difference in terms efficacy and safety are not yet known. Importantly, to date, the LIBERTY,9 FOCUS (fremanezumab)12 and recent CONQUER (galcanezumab) trials16 have included patients treated unsuccessfully with between two and four preventive treatments (Table 1). The efficacy of eptinezumab remains untested for patients with severe, treatment-resistant migraine.

There are potential limitations to the use of anti-CGRP antibodies. The duration of trials, to date, is not sufficient to determine the long-term effects of continuingly blocking CGRP or its receptor. CGRP is an ubiquitous peptide that is not only involved in migraine, but also in several other physiological processes.20 Since this is a new drug class, continued monitoring of efficacy and safety, including production of toxic metabolites, and the production neutralizing antibodies, is important.21 In the cardiovascular system, CGRP is present in nerve fibres that innervate blood vessels and the heart and are involved in the regulation of blood pressure.22,23 Patients with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease were, therefore, excluded from clinical trials. Although no increased incidence of cardiovascular events was reported in the clinical trial, further studies should examine the cardiovascular effects of the long-term, continuous blockade of the CGRP pathway.

One potential barrier to the widespread use of these agents is cost; the price of the drugs has to be taken into consideration when deciding whether to use CGRP antibodies as a prophylactic treatment and which patient groups to treat. The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review concluded that CGRP inhibitors are cost-effective in the long-term but could potentially have a significant impact on short-term health budgets.24 The LIBERTY study has identified an important subgroup of migraine sufferers who will derive benefit from treatment, increasing its cost-effectiveness.

In summary, on the basis of current evidence, anti-CGRP antibodies have the potential to improve the lives of millions of people suffering from frequent migraines. Erenumab appears to be a particularly attractive option for patients with difficult-to-treat migraine who have high unmet needs and few treatment options.